Welcome to Waverley Cemetery, where the dead rest and the living ponder. And wander. I’d taken a bus across Sydney on a bright, sunny morning to get here. Because of the way I’d come, I entered through a side gate instead of the front, and it felt like I’d accidentally stumbled onto the set of a B-grade horror film. Well, a B-grade horror film with an extremely generous budget for sets. But fear not, dear reader, for this is no tale of terror—merely a jaunt through one of the most beautiful cemeteries in the world.

I stepped into this Victorian-era necropolis perched precariously on the cliffs above Bronte Beach and immediately marveled at the irony. Here I was, surrounded by 90,000 dead souls,1 and yet the view was so breathtakingly alive it made me want to break into a rendition of "The Hills Are Alive" from The Sound of Music. But I refrained, I refrained. Everyone around me was already dead, so it seemed cruel to subject them to any more horror.

Before you start thinking I'm some morbid weirdo who spends weekends prancing through graveyards,2 let me assure you that Waverley Cemetery is no ordinary bone orchard. Oh no, Waverley is where the crème de la crème of Australian society goes to spend eternity with an ocean view. It's like a gated community for the deceased, where the price of admission is, well, death. As I meandered through the rows of ornate Victorian and Edwardian monuments, I couldn't help but be impressed by the sheer extravagance of it all.

But let's not get ahead of ourselves just yet. Waverley Cemetery, established in 1877 on the land of the Bidjigal and Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, is more than just a pretty face. It's a veritable Who's Who of Australian history, a stone-cold3 lesson in the characters who shaped this sunburnt country.

Take Henry Lawson, for example. Born in 1867 to a Norwegian gold prospector and a poet mother, young Henry went deaf at 14. But did that stop him from becoming Australia's greatest writer of short stories? Not on your life! His works helped popularize Australian vernacular fiction. He wrote prolifically in his 20s but struggled with alcohol and mental illness and spent time in jail and asylums. When he died in 1922, he was the first Australian writer to be given a state funeral.

Finding Lawson's grave, however, was an adventure in itself. I was hoping the office lady would just say, “Don't worry about a thing, hon. I’ll get Bob here to drive you over.” Yeah, no chance. But she did hand me a barely useful map and sent me on my way.4 Fortunately, in addition to maps, the cemetery maintains the occasional pointer to famous people’s gravesites. Whoever is in charge of those red signs deserves our thanks.

So there I was—Henry Lawson, Australia's poet and story writer, born June 17, 1867, died September 2, 1922. The inscription read, “Love hangs about thy name like music round a shell, no heart can take of thee a tame farewell.” Dang. Poetic even in death. Well played, Henry. Well played.

As I stood contemplating Lawson's legacy, I couldn't help but think of another Henry—Henry Kendall. Because he’s buried under a very ornate monument. You can’t really miss it.5 Kendall was considered Australia’s greatest poet, renowned for his poems and stories set in the natural environment. Kendall was born in 1839, nearly three decades before Lawson. Life wasn't kind to old Henry K—he suffered from poor health and bouts of melancholia, and he died of consumption in 1882.

But here's where the story gets interesting. Kendall was originally buried right next to where Lawson now rests. Ultimately, though, his remains were moved to another, grander plot. If that hadn’t happened, these two great Australian literary figures would now be lying side by side for all eternity.6 And who do you think organized the upgrade for Kendall? Lawson’s mother, Louisa Lawson, yet another celebrated Australian poet.7 It's like a literary soap opera, I tell you.

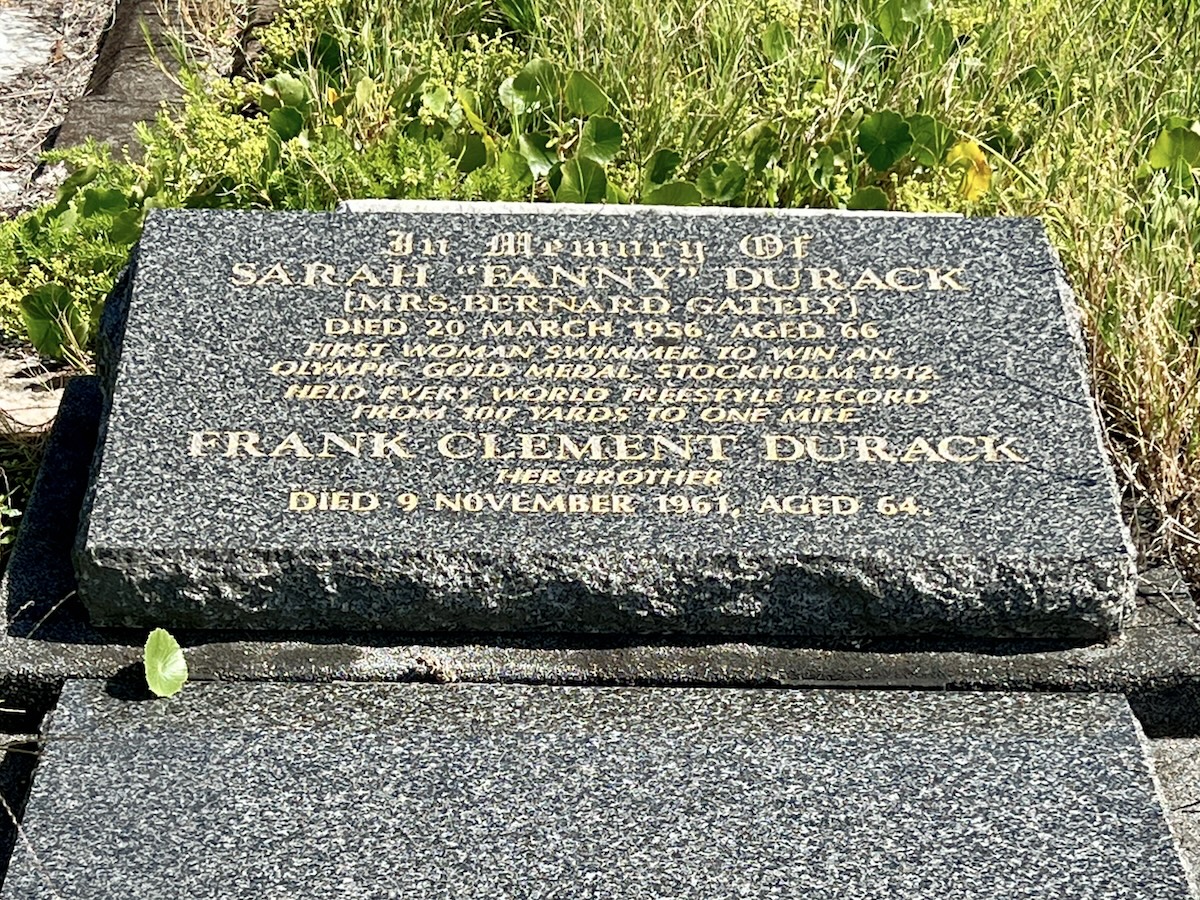

Then there's Fanny Durack, the Michael Phelps of the early 20th century.8 From 1910 to 1918, Fanny was the aquatic queen, holding every world record from 100 yards to a mile. She was the first woman to win an Olympic gold medal in swimming, and she did it in 1912 when women in Sydney were still forbidden from competing in front of men. I can just imagine the conversation:

Sorry, Fanny, you can't compete in front of men. It's unseemly for a lady.

But I'm the fastest swimmer in the world!

Yes, but think of the men's delicate sensibilities.

*splash*9

Dorothea McKellar is there, too, author of the famous-in-Australia poem My Country.

I love a sunburnt country

A land of sweeping plains,

Of ragged mountain ranges,

Of droughts and flooding rains.

It's the poem that every Australian school child can recite by heart,10 usually while staring longingly out the classroom window at the concrete jungle of suburban Melbourne or Sydney. Ah, the irony.

But it's not all poets and athletes in this marble metropolis. Oh no, we've got some real characters, too. Like Robert "Nosey Bob" Howard. Nosey Bob, the longtime hangman and executioner for the New South Wales Colony, was responsible for the state-ordered deaths of 61 men (and one woman) —murderers, rapists, amateur abortionists, and bushrangers all.

Howard came to Sydney around 1870 and owned a fairly successful cab business. Something happened in 1873, though, that cost him his nose.11 And it turns out that the lack of a complete face isn't good for business in the service industry. Desperate, he took the only job that paid a decent wage and steady work. For nearly 30 years, Howard was the go-to guy when someone needed a good hanging. Talk about a conversation starter at parties.12

Howard wasn’t like other executioners, though, who typically came from backgrounds rife with poverty, alcoholism, and insanity. Nosey Bob always showed up on time, abstained from drinking on the day, and always remarked to the condemned, “My poor man, no one regrets this more than I do.” He ultimately built a cottage above Bondi Beach with sea views where he kept a tidy garden, grew vegetables, had pet dogs, and kept bees. Bondi is next door to Waverley, so Nosey Bob didn’t have far to go when his end came.

Victor Trumper, “the most stylish and versatile batsman of the Golden Age of cricket, capable of playing match-winning innings on wet wickets his contemporaries found unplayable,” is also buried at Waverley. But because I know very little about cricket and care even less to learn about it, I have nothing to say about him.

Way more interesting is Wee Davie’s grave. Wee Davie (David Herbert Forde, technically) died on January 13, 1878, at the tender age of 4 years and 5 months. Sad, yes, but there’s more. For years, the story was that Wee Davie was an unknown child run down by a butcher's cart. He only managed to whisper his name before shuffling off this mortal coil, leaving the distraught butcher to bury him under the name “Wee Davie.” Absolutely Dickensian.

And absolutely BS. Wee Davie actually died of diphtheria at home in the suburb of Glebe Point. The myth persisted for decades until Davie's father, probably tired of all the melodramatic nonsense, wrote to The Bulletin in 1917 to set the record straight. Interestingly, Wee Davie was the first to be buried in the Catholic section and only the 22nd burial in the entire place.13 The inscription on his grave reads, "Somebody's darling lies buried here," inspired by the poem "Somebody's Darling" that his father was particularly fond of. It's enough to make even the most hardened cynic feel a twinge in the old heartstrings.

Somebody's watching and waiting for him.

Yearning to hold him again in her heart;

There he lies—with blue eyes dim, And smiling, childlike lips apart.

Tenderly bury the fair young dead

Pausing to drop on his grave like a tear;

Carve on the wooden slab at his head—

"Somebody's darling lies buried here!"

A bit treacly for my taste, to be honest.

Finally, and this one was actually on my list, I found Evelyn James’ grave. “Who?” I hear you asking. This lady had a date with destiny, friends, as the only Australian female survivor of the Titanic. Our Evelyn had a front-row seat to one of history's most infamous nautical disasters.

A nurse in Melbourne, Evelyn got bit by the travel bug and left for England in 1908, where she hung out with her extended family and got engaged to a Welsh physician, William James, who worked as the ship's doctor. Evelyn loved the idea of working on a ship, so she got a job on the Olympic and was on board when that ship collided with another one in 1911.

Undeterred, she signed on to the Titanic as a stewardess on April 6, earning £3 and 10 shillings monthly. After hitting the iceberg around midnight,14 Evelyn found herself in Lifeboat 16 and spent what I assume was a delightful night bobbing about in the freezing North Atlantic and chatting up passengers until the Carpathia picked them up at 7 in the morning. Upon her return to Britain, she sent a cable to her anxious parents back in Australia that read simply, "Safe. Evelyn."15 At this point, she may have seen the writing on the wall and promptly married William and moved back to Australia. By ship. I mean, bravery or madness, you've got to admire her commitment to ocean cruises at this point.

As I continued my stroll, I came across graves from various eras. Some dated back to the 1800s, while others were more recent, from the 1930s to the 1960s. I even spotted one from 1992—Robert Duval Goatley, if you're curious. I have no idea who he is. But it got me thinking about the ongoing nature of this place. Waverley Cemetery is still a functioning cemetery, still accepting new residents into its clifftop community. Although looking at the crowded landscape of headstones, I couldn't help but wonder where on earth they're putting them all. It's like a game of Eternal Tetris up there.

I also couldn't help but notice the stark contrast between the opulent tombs of the colonial elite and the simpler graves of the working class. It's as if, even in death, the class system refuses to loosen its bony grip. I half expected to see a spectral butler polishing the marble of some long-dead aristocrat while a ghostly chimney sweep looked on enviously.

But it's not all jealousy-inducing views and grand monuments. As I wandered, I came across a lot of graves in various states of disrepair. Some headstones were sinking into the ground, others were lopsided or had collapsed entirely. It was a stark reminder of the ongoing battle between human memory and the relentless march of time.16

I looked up the cost of repairing these old headstones, and it can range anywhere from $2,000 to $5,000 to restore a single gravestone. Apparently, death is the great equalizer, but not if you're buried at Waverley. Here, the afterlife comes with a view and a price tag to match. It's enough to make you consider cremation, isn't it?17

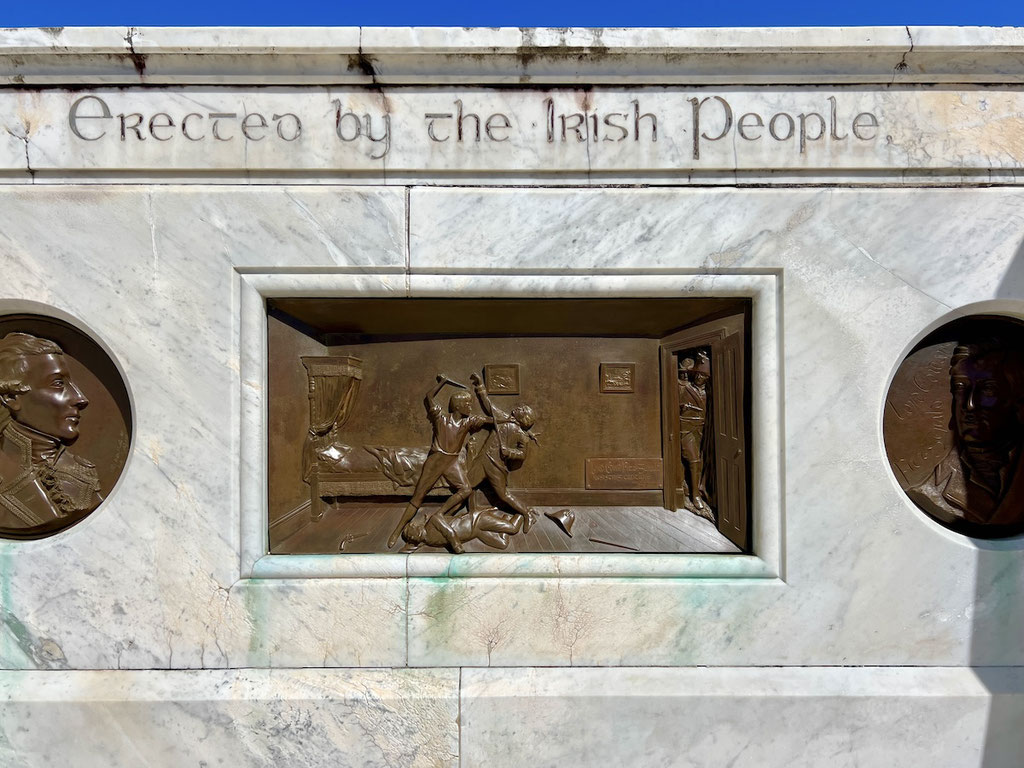

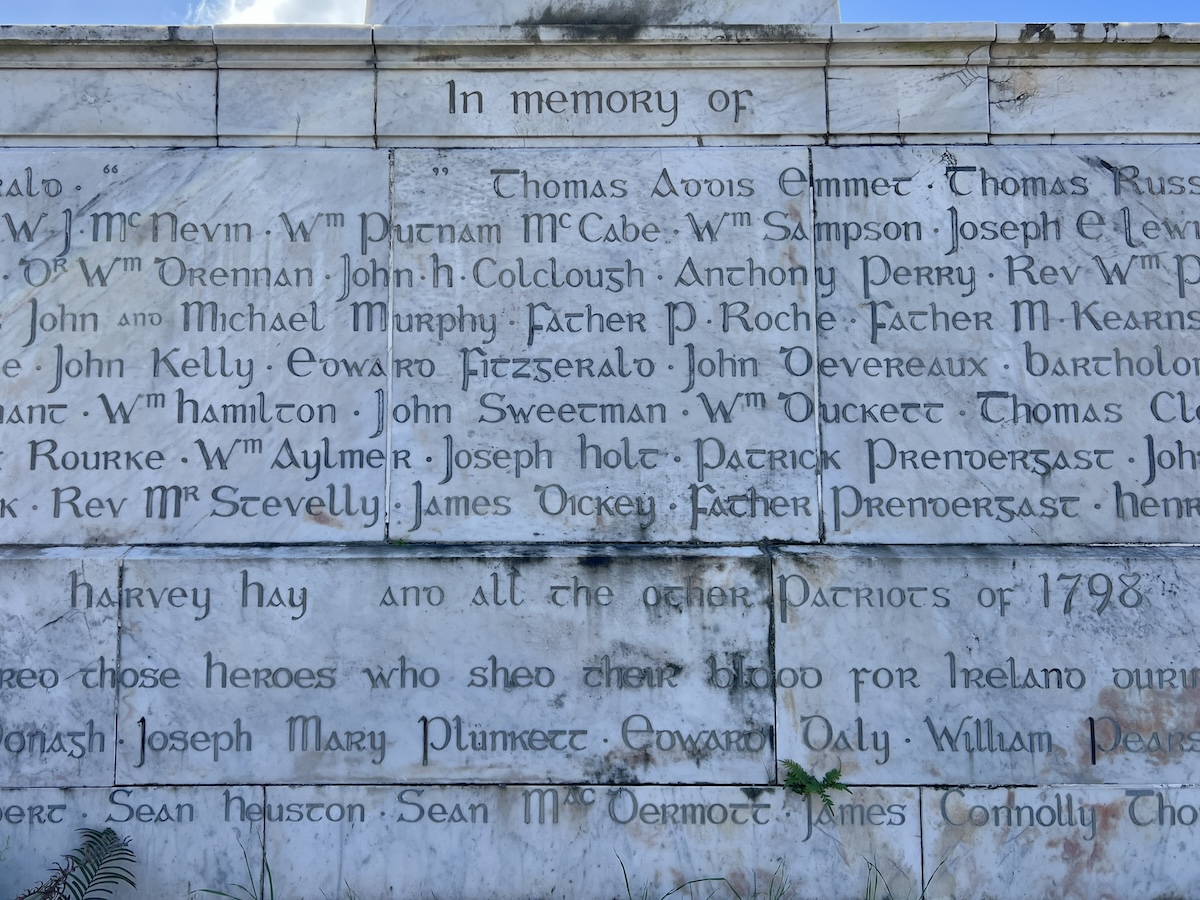

Oh! And then there’s the Irish Martyr’s Memorial! It’s the largest monument in Waverley and possibly the biggest Celtic-themed structure this side of Dublin. Honestly, this thing is so massive that you have to wonder if the Irish are compensating for something. Constructed in 1898 to commemorate the rebellion of 1798,18 this behemoth is like someone took every Irish cliché, threw it in a blender, and created the world's most patriotic smoothie.

The (mostly ornamental and completely ineffectual) fence is adorned with battle shields, Irish harps, battle axes, crossed swords, and Irish wolfhounds. Really? Where are the clovers?19 The centerpiece features a medallion of Michael Dwyer, the "Wicklow Chief" (I assume he earned this title by being exceptionally good at herding sheep).

The memorial lists names of various Irish rebels through the ages, including a conspicuously absent Thomas Emmett, who apparently said he only wanted an epitaph once all of Ireland was free from the English.20 Talk about playing the long game.

This Celtic colossus inspires awe and amusement—a testament to the Irish spirit, their love of a good rebellion, and their apparent inability to do anything by halves.21

This seemed like a good place to end my tour of the Waverley Cemetery, which I decided was more than just a final resting place—it's a time capsule, a museum, a testament to the human desire to be remembered long after we've gone to (I hope) our reward. It's also a stark reminder of Australia’s colonial past, with its grand monuments to the pioneers and settlers who built modern Australia on the backs of the Indigenous peoples whose land they claimed. As a reminder, this amazing cemetery sits on Bidjigal and Gadigal land, a fact that shouldn't be forgotten amidst the marble angels and Celtic crosses.

But most importantly, Waverley Cemetery is a place that forces us to confront our own mortality. As I stood among the graves, with the endless expanse of the Pacific stretching out before me, I couldn't help but feel small, insignificant, and yet strangely connected to something greater than myself. It's a place that reminds us that life is fleeting, that our time here is limited, and that maybe, just maybe, we should spend a little less time worrying about what kind of monument we'll leave behind and a little more time enjoying the view while we still can.

Oh, and there was a kookaburra. I love kookaburras.

Oh, you know, a bit of this, a bit of that. I used to own a cab company in town. Now I mostly just hang people.

...

More punch?

Write a comment