Airlie Beach, about two-thirds of the way up the Queensland coast from Brisbane, is a tiny town with an outsized reputation—population 1,312; annual visitors, half a million plus. After Noosa and Cairns, Airlie Beach is probably the most touristed coastal town in the whole of Queensland.1 Town is a colorful mishmash of backpackers, families, and yachters, all converging on this lively coastal town with sun hats, snorkels, and sunscreen in hand.

All the commotion exists because Airlie Beach is known, rightfully, as the launchpad to the Whitsunday Islands and the Great Barrier Reef, the bustling front door where the Coral Sea adventure begins for hundreds of thousands of visitors. We've all heard of the reef, even up north. But I don't think many of us understand its full scope.

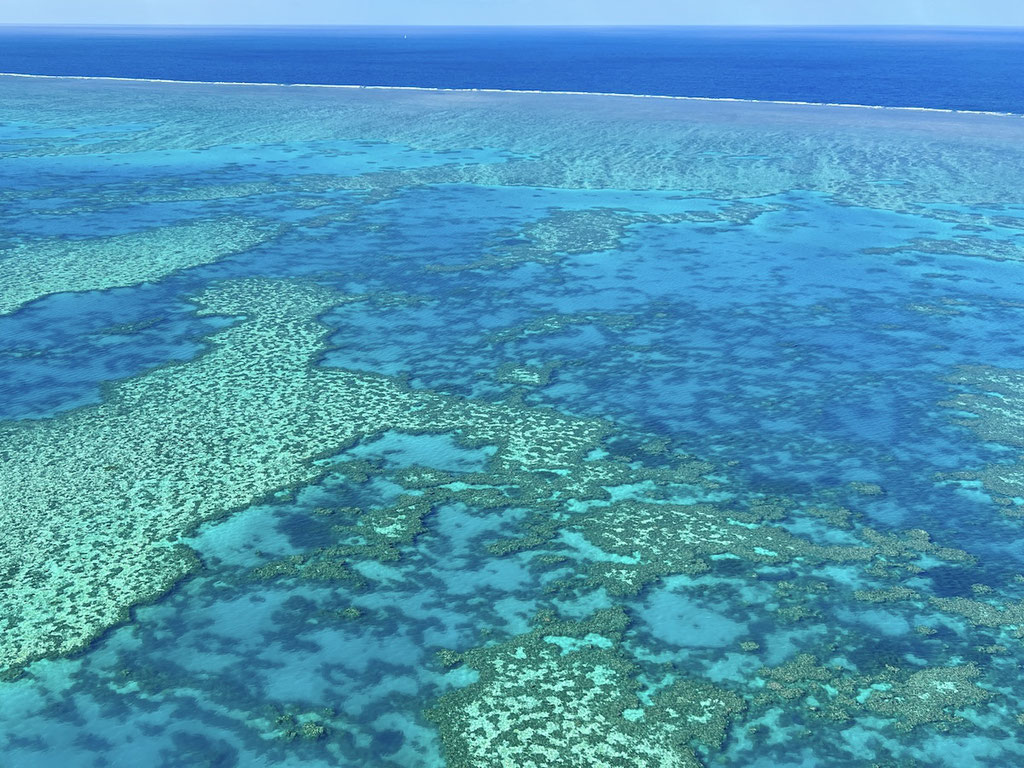

The Great Barrier Reef stretches along 1,400 miles of the Queensland coast.2 The planet's largest reef comprises roughly 3,000 individual reefs and 900 islands. Visible even from outer space and about the size of Italy, it's home to more than 1,500 species of fish, six of the world's seven species of sea turtles, and roughly 30 types of whales, dolphins, and porpoises. More than a stop on the tourist train, it’s a living, breathing wonder that’s held its own over millennia. The reef was named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1981.

But as much as Airlie Beach has going on at street level, the real magic is best appreciated from above, where the crystal waters, island-studded horizons, and coral reefs stretch out in breathtaking detail. Which is why we found ourselves headed to nearby Shute Harbour for a flight over the reef early one suspiciously perfect morning.3 The water was as smooth as glass, the air was almost crisp, and we half-expected a film crew to pop out, ready to capture b-roll for a Nicole Kidman rom-com.

Our chariot awaited—a twin-engine plane so small it looked more like a lawn ornament. Our pilot greeted us with that mix of confidence only rockstars and pilots seem to possess, rocking a casual smile and enough tattoos to suggest she knew how to handle more than just turbulence. After a “safety chat” that was brief, concise, and delivered with all the enthusiasm you’d expect from a Millennial politely tolerating yet another bunch of over-eager Gen X tourists.4 Whatever, we excitedly piled in and buckled up. The engines rumbled, and the world below us began to shrink as we soared into the endless blue-green sky of central Queensland.5

As we climbed into the sky, the Whitsundays appeared, 74 islands tossed into the sea like confetti.6 Most of the islands were thick with jungle, lush and untamed. The vast majority—more than 60—are entirely untamed, with no permanent human inhabitants. As part of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, they remain in their natural state, home only to native flora and fauna. Most can only be accessed by boat for day trips, camping, or hiking. Tancred and Denman Islands were the first Whitsundays we flew over, wild little specks, untouched by development and blanketed in thick greenery. From up here, they looked like a perfect castaway’s haven.7

Just past Tancred and Denman, Whitsunday Island—the largest of the Whitsundays—stands as the namesake and crown jewel of this iconic island group. With nearly 42 square miles of lush forests, dazzling beaches, and rugged peaks, it’s a slice of paradise. When Captain Cook sailed through in 1770, he named the region for Whitsunday8 because that’s what day he thought it was. But he was actually a day late. Stupid International Date. Whitsunday Island played an unexpected role as a strategic lookout point during WWII. Allied forces were stationed there to watch for enemy ships. Today, these remnants of its past stand quietly against the natural beauty, adding a touch of intrigue to an island that remains otherwise untouched by time.

The white-hot star of the Whitsundays, though, is Whitehaven Beach on the far side of Whitsunday. Holy underpants, what a beautiful spot. As we crested the island, Whitehaven stretched out below us like a giant ribbon of powdered sugar. This sand, much like that found further south on K’gari, is composed of very nearly pure silica (98.9% silica),9 which means it’s the kind of sand that stays cool no matter how hot the day gets. A great perk in an area where the sun can be relentless.

Whitehaven's immediate neighbor is Hill Inlet, with its swirling blue and white patterns. The inlet is in constant motion. Unlike the straight stretch of Whitehaven's sandy shores, Hill Inlet is all about movement and transformation. As the tides ebb and flow, the sands and water shift, creating ever-changing patterns. From above, the inlet’s mosaic of blues and whites is hypnotic, a dynamic work of art that’s never quite the same twice. Clearly one of the several “money shots” of the tour, Pilot graciously looped around a few times to make sure we could all soak it in. Our phones and cameras were snapping like paparazzi, but no picture can really capture it.

Today, Whitsunday Island, Whitehaven Beach, and Hill Inlet are bucket-list items for countless tourists every year. it was home to the Ngaro people for more than eight millennia—the original "locals.” They moved seasonally across the Whitsundays, leaving their mark in rock art and ancient sites that modern scientists are still finding. The Ngaro crafted bark canoes to skim these waters and honed clever fishing techniques that made the most of their abundant surroundings. For the Ngaro, Hill Inlet was a sacred place where tides and land met in a way that was both spiritual and practical. The shifting sands are a reminder of Dreamtime stories, according to Ngaro legends, representing the connection between land, water, and spirit.10

Leaving Whitsunday Island behind, we drifted over the lesser-known outer Whitsundays, each a little world of its own. Border Island’s jagged cliffs and bright coral gardens make it a snorkeler’s dream. Cateran Bay has water that is so clear you can practically see individual sea turtles and reef sharks from the air. Beyond Border Island sits Dumbell Island. Maureen's Cove, on its western side, is a kaleidoscope of coral and parrotfish, with giant clams and soft corals adding to the spectacle. At the outermost edge of the Whitsundays are islands like Deloraine and Eshelby, untouched, raw, and remote. None of these islands have any facilities. It’s just you, the islands, and the fish.

Just past the islands, we neared the leading edge of the Great Barrier Reef—Hardy Lagoon. The Lagoon is one of those places where the reef itself creates a "barrier," forming a calm, shallow lagoon protected from the open sea. From above, it looks like a sandy beach just below the surface, though it's really a thin reef layer stretching out under the clear water. The light sand and coral beds give the whole area a surreal glow like the colors were cranked up a notch just for effect.

The sheltered waters make Hardy Lagoon a haven for marine life, with fish and coral flourishing in this quiet little aquatic garden. The difference is striking—on one side, you have this serene, almost pastel-colored paradise, while just beyond the reef, the deeper ocean darkens and intensifies. Floating over Hardy Lagoon feels like finding something private that nature tucked away, where everything is pristine by design.

Further out over the Coral Sea, the magic of the Great Barrier Reef comes into full focus. The reef stretches out, a vast and vibrant tapestry sewn into the ocean floor. Coral patches bloom in colors you wouldn't expect in the middle of the ocean—lavender, aquamarine, cobalt, emerald. Up here, we could appreciate the full size of the reef. Almost immediately, Pilot announced that Heart Reef was coming up, a tiny coral formation nestled in Hardy Reef that’s, spoiler alert, naturally shaped like a heart. It’s small but perfectly formed and, honestly, worth every bit of the hype. We circled it twice so we’d all get a good look. There’s something poetic about a heart-shaped reef in the middle of the Coral Sea, like nature’s little love note, and seeing it in person added a touch of romance to the adventure. No one is allowed near it, not snorkelers or divers of boaters, so it stays pristine—a little secret that only flyers get to see.

Here's where Pilot pointed out a fascinating natural phenomenon—a river in the ocean. Really tidal channels that weave among the reef structures, the currents resemble nothing more than river flows. These channels are vital for the reef's health, facilitating water circulation, nutrient distribution, and providing pathways for marine life. The sinuous channels contrast with the surrounding coral formations, highlighting the dynamic interplay between the reef and the ocean's movements.

As we began to turn back toward home, we saw something unexpected. Humpback whales! We could see a pod splashing and spouting below.11 These whales journey from the icy waters of Antarctica to the Whitsundays to breed and raise their young. Wow. Even from high above, they made me feel small.

Pilot filled the time between sights talking about the reef’s incredible biodiversity. It's an underwater metropolis, teeming with life in all forms—tiny clownfish hiding among anemones, sea turtles drifting leisurely, and corals of all shapes and colors. It’s easy to see why so many people fall in love with it at first sight, but seeing it from above added a new layer of awe.

But the reef’s beauty is also its vulnerability. Warming ocean temperatures, coral bleaching, pollution, and human interference threaten its survival every day. Conservation efforts are underway, but the scale of the reef makes it a monumental task. Seeing the expanse from above made the situation real in a way that headlines and articles never could.

The Whitsundays and the Great Barrier Reef are more than just tourist stops. They teem with life, history, and beauty that defy explanation. After coming back down to Earth—figuratively and literally—we headed back to our Airbnb with our heads full of images we knew would stick with us for a long time. Our pictures don’t do it justice, but it was amazing. Maybe that’s another thing that makes a place like this so special—it can't be fully captured, not in words or photos. It's an experience that demands to be felt, seen in the moment, and carried forward as a memory.

Write a comment