The sun-soaked metropolis of Brisbane is home to the largest City Hall in Australia. Which sounds pretty great until you read the small print—it’s also the only city hall in Australia. Every other place has a Town Hall. To-may-to, to-mah-to.

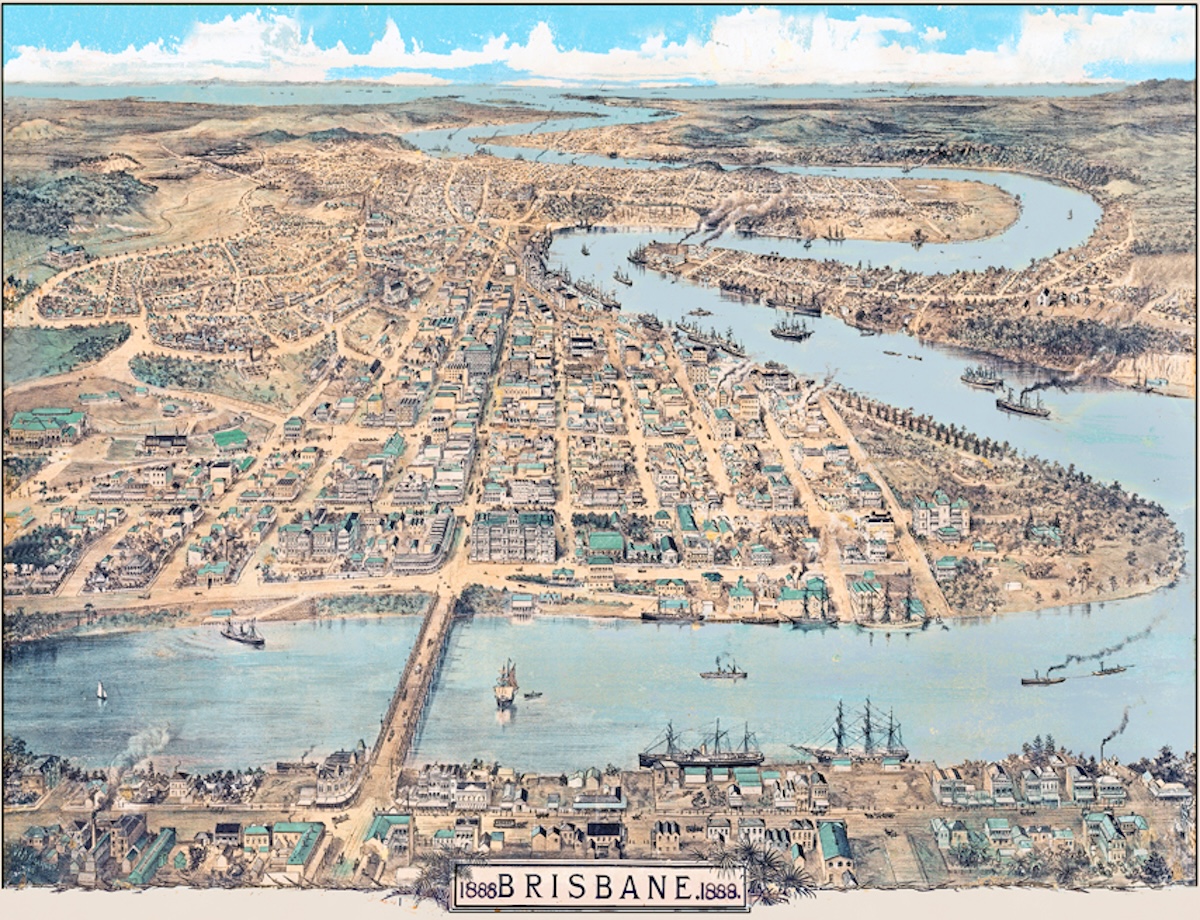

But first, a bit about Brisbane. It is, notably, the third-largest city in Australia; its river is the third-longest in Southeast Queensland, and its cricket ground is the third-oldest in the country. Their beloved Story Bridge is the third-longest cantilever bridge in Australia. Brisbane's Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary, founded in 1927, is the world's third-oldest (but second-largest) koala sanctuary. Oh! And the Bee Gees! Those falsetto-wielding disco kings got their start in Brisbane, though only Barry was born here. So technically, the city can claim to be responsible for a third of the band.

Honestly, I’m surprised they haven't petitioned to change their name to Thirdsbane.1 You might think being perpetually third would be a source of embarrassment. But Brisbane wears it like a badge of honor. It's the Jan Brady of Australian cities, constantly crying, "Sydney, Sydney, Sydney!" while secretly plotting to steal Melbourne's lunch money.

It wasn’t always third in everything, though. It was, for instance, the fifth major penal colony established in Australia. Governor Brisbane of the New South Wales colony—which technically included the entire eastern half of the Australian continent—needed a place to send Sydney’s secondary offenders.2

Sydney was the primary drop-off point for England’s criminals, but England had become really, really good at creating criminals. So the sewer pipe to Sydney just kept spewing out more criminals than Sydney could safely house. “Right. Sydney's getting a bit crowded with all these pickpockets, petty thieves, and potty mouths. Where can we send the real ratbags?”

So he ordered his Surveyor General, John Oxley, to explore north along the coast in 1823 to see what he could find. And what he found were two escaped convicts who’d been living with the Aboriginal people on Moreton Island. With their help, he found the mouth of the Brisbane River.3 Success!

The original Moreton Bay Penal Settlement was established in Redcliffe a year later, roughly 25 miles north of what is now downtown Brisbane. But, like so many Australian settlers before them, they soon realized they'd chosen precisely the wrong spot. Massive clouds of mosquitoes and disgruntled Indigenous folk made for less-than-ideal neighbors, and the sandy soil refused to grow anything but disappointment. So they packed up their meager belongings and moved to Brisbane. Even in the 1820s, it was all "location, location.”

As a place of secondary punishment for re-offenders—the worst of the worst—the colony was infamous for its harsh conditions and strict discipline.4 But it only lasted 15 years, not long in the grand scheme. The penal colony was closed by order of the governor in 1839, and the area was opened to free settlement in 1842. Many locals decided maybe the skeeters weren't so bad and they stayed on, becoming Brisbane's first families and proving that Stockholm syndrome was totally a thing well before we named it that 130 years later.

Queensland became its own colony separate from New South Wales in 1859, with Brisbane as its capital. Brisbanites celebrated by immediately starting to complain bitterly about the weather. Not five years later, the city decided to spice things up a little by accidentally burning down in what was imaginatively named the Great Fire of Brisbane. It was a lot like the Great Chicago Fire and the Great Seattle Fire, but the flames swirled in the opposite direction. And I’m just guessing, but I would assume Brisbane’s was the third-most spectacular of the three.

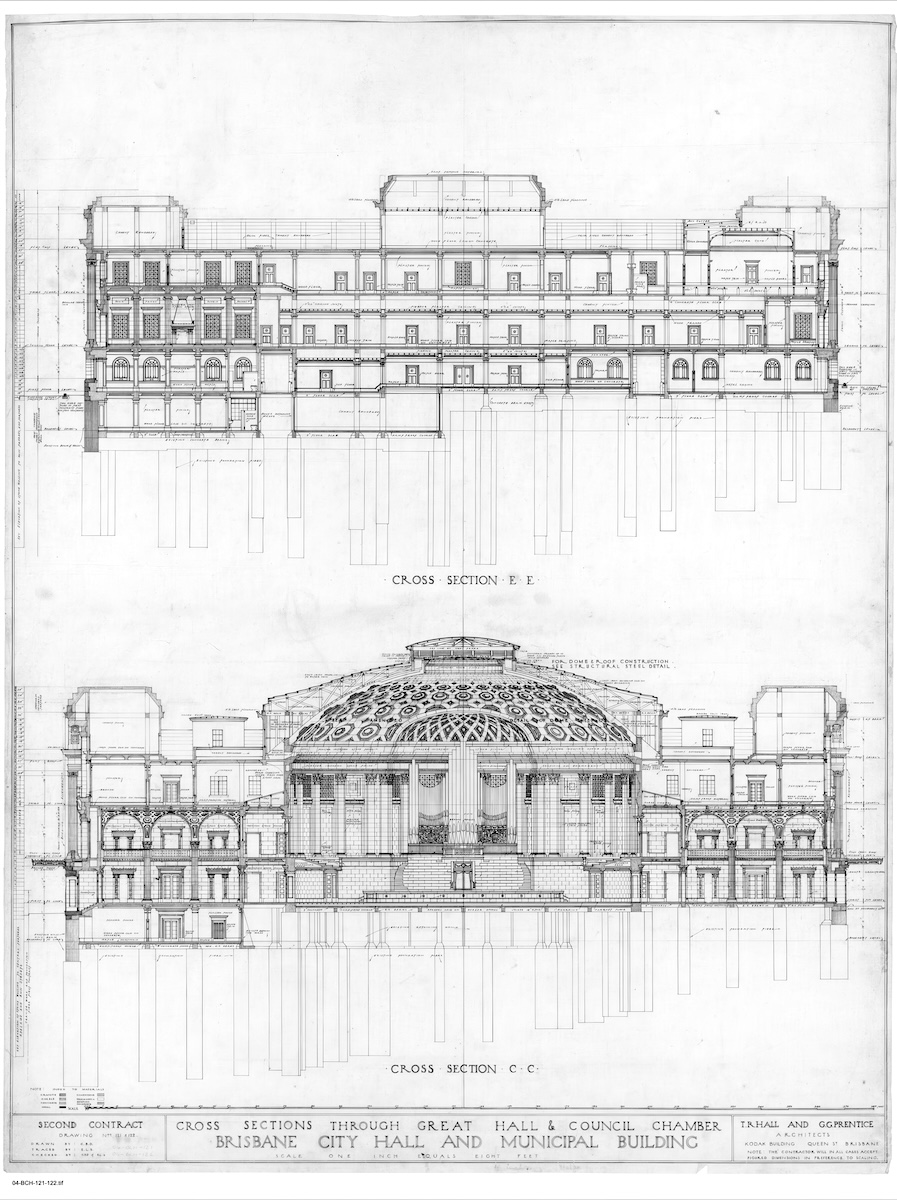

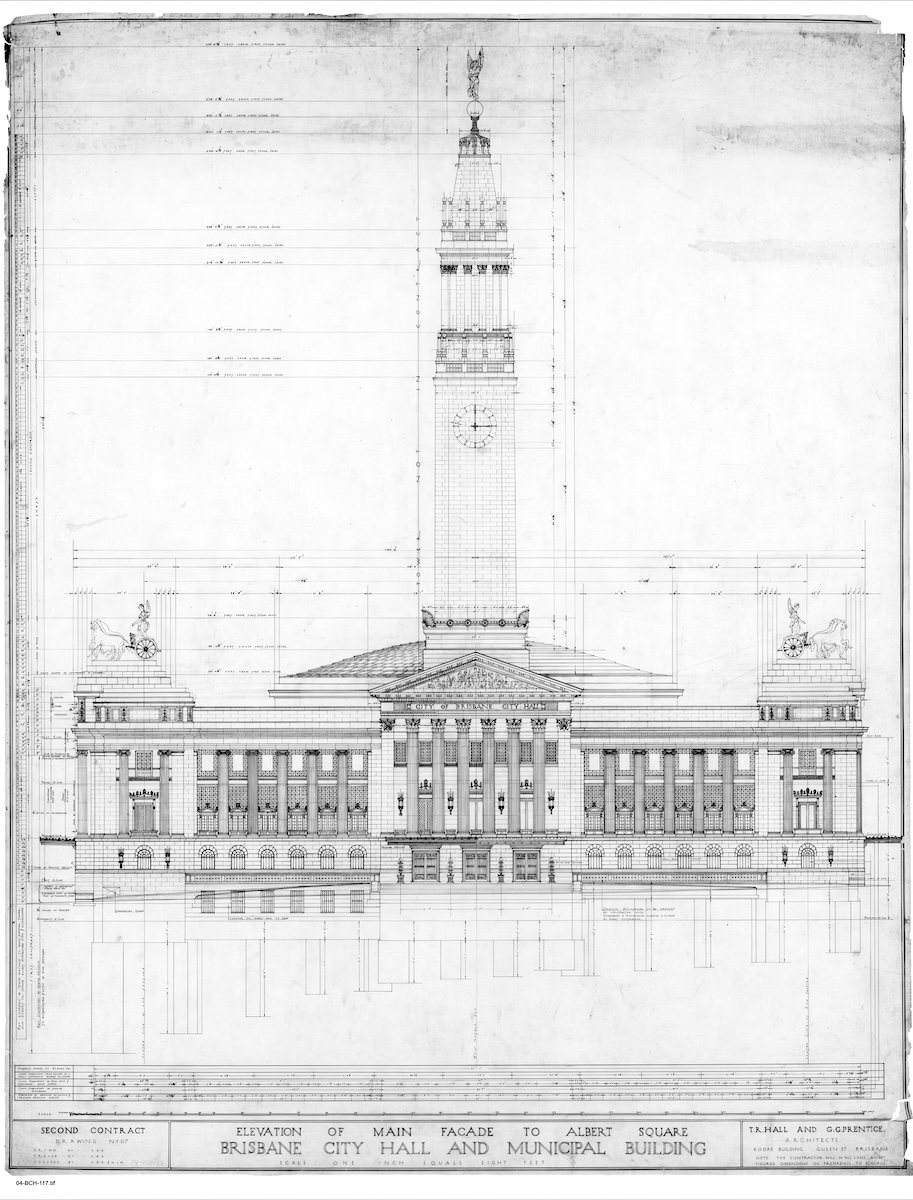

By the early 1900s, Brisbane’s city fathers decided they needed to make their mark, so they proposed a fancy new City Hall. Nothing says, "We're practically as good as Sydney or Melbourne," quite like a grandiose building slowly sinking into the swamp. Construction began in 1920 and took 10 long years. Obviously, Brisbane has always run on “tropical time.”

The construction site was once home to horse stables and a marshy pond, which explains the building's subsequent structural challenges. At the time, it was Australia's second-largest construction project after the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The foundation stone was laid in 1917 by Queensland Governor Sir Hamilton Goold-Adams with thousands of Brisbanites in attendance.5 The stone contained a cylindrical zinc time capsule filled with coins, newspapers, and historical records in case future generations need proof that early 20th-century folk had questionable taste and an unhealthy obsession with King George V.

When they finally got around to laying down bricks and stone three years later, though, after countless design “refinements,” they discovered that the foundation stone was no longer aligned properly. Turns out Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) was on his way down south for a visit. So instead of digging up the first stone and correcting its alignment, they decided on a new one for the future king to lay. Which he did in July 1920.6 Construction then began in earnest. The Lord Mayor moved into his office in 1928, though the building wasn’t officially complete until 1930, just as the Great Depression was getting into full swing.

After a decade of construction, countless setbacks, and enough drama to fuel a soap opera, Brisbane City Hall finally opened its doors to another cheering crowd of thousands of Brisbanites

celebrating the last day any of them had any spare change their shiny new civic center. Queensland Governor Sir John Goodwin did the honors, using a giant golden key that probably cost

more than the average citizen would see in a year.

The building is a neo-classical masterpiece with a sandstone façade, mosaic tiles, and stained-glass windows. It covers two acres and boasts 573 rooms, including the Lord Mayor's office and Council Chambers. The massive entrance from King George Square features columns that soar nearly 46 feet to support a tympanum created by locally renowned sculptor Daphne Mayo that is a crash course in questionable historical narratives. Titled Settlement of Queensland, it’s a snapshot in stone of 1920s Australian political incorrectness. The female personification of Progress stands with arms spread protectively over white settlers with their cattle and explorers with their horses, all fanning out to claim the land from the indigenous people and native animals. These are represented by two Aboriginal men crouched defensively in the lower left corner and a fleeing kangaroo.7

The crown jewel of City Hall is its clock tower, whose 300-foot height made it the tallest building in Brisbane for nearly 40 years. The locals call it "Brisbane's Big Ben," even though it was fashioned after the Campanile in Venice and is nearly 15 feet shorter than its namesake.8 But hey, who's counting?9

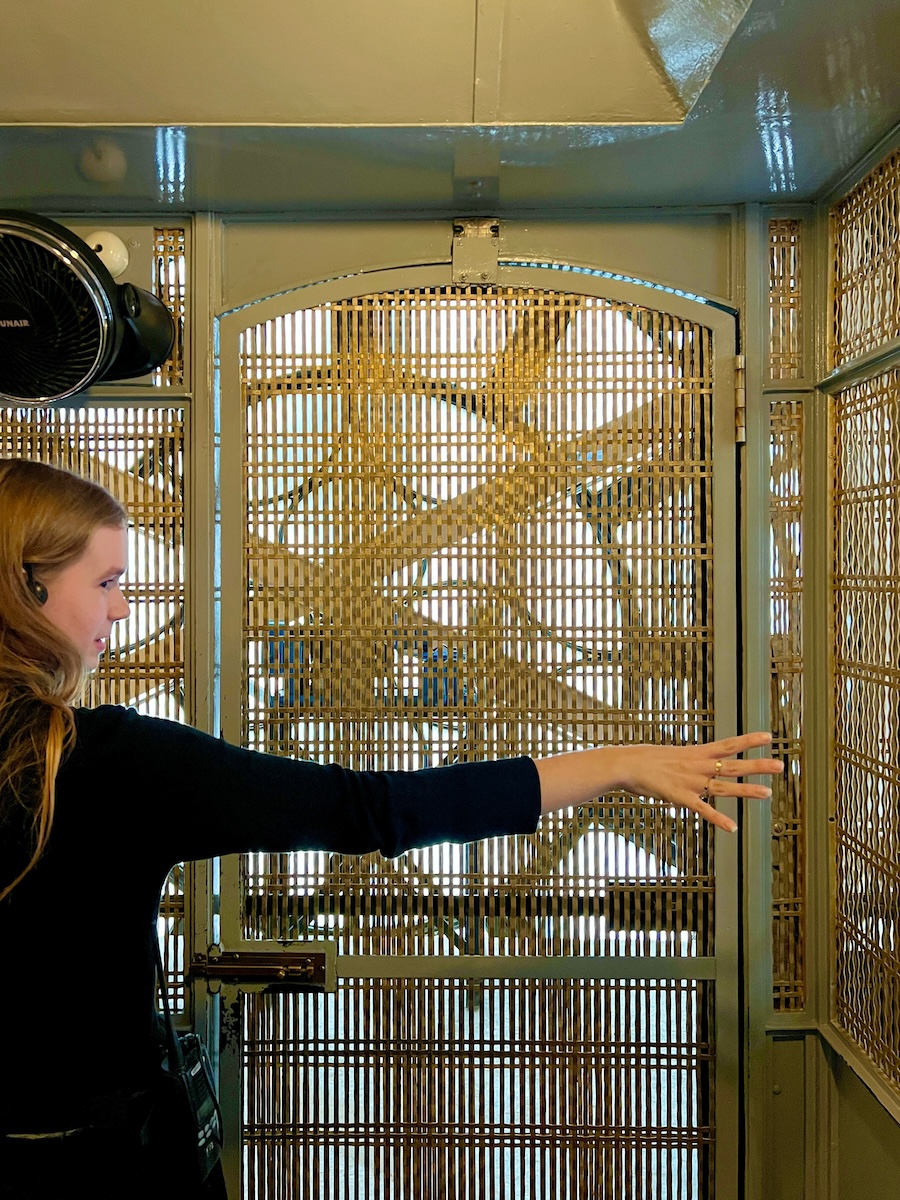

Inside the tower is one of Brisbane's oldest working cage elevators, which is still operated manually, like a really cool steampunk time machine that only goes up and down. Initially closed to the public, the elevator operators started taking visitors to the top of the tower—sixpence for adults and thripence for children10—to enjoy a 360-degree view of the city. The tower is home to Australia's largest analog clock. When it was built, it was the largest and most modern timepiece in Australia. The face is made from white opal and is nearly 16 feet in diameter, with a minute hand almost 10 feet long.11

Another highlight is the central auditorium, which was inspired by the Pantheon in Rome and has a massive copper-roofed dome more than 100 feet in diameter. The dome is designed with no internal pillars to obscure the audience’s sightlines. Mayo also created the decorative proscenium frieze above the stage, which features six life-size nymphs playing trumpets and cymbals.12 The auditorium has hosted countless performers, but the most memorable may have been the Rolling Stones in 1965.

The auditorium is also home to a magnificent pipe organ with nearly 4,400 pipes.13 One of only two five-manual Father Henry Willis Organs left in the world, it was built in 1892 in London for the Queensland National Agricultural and Industrial Association (QNA), an organization that declared bankruptcy in 1897. Local musicians and residents joined forces—and their pocketbooks—to purchase the organ at auction. It sat for several years before being enlarged and refitted in 1928 to prepare it for its new home in City Hall.

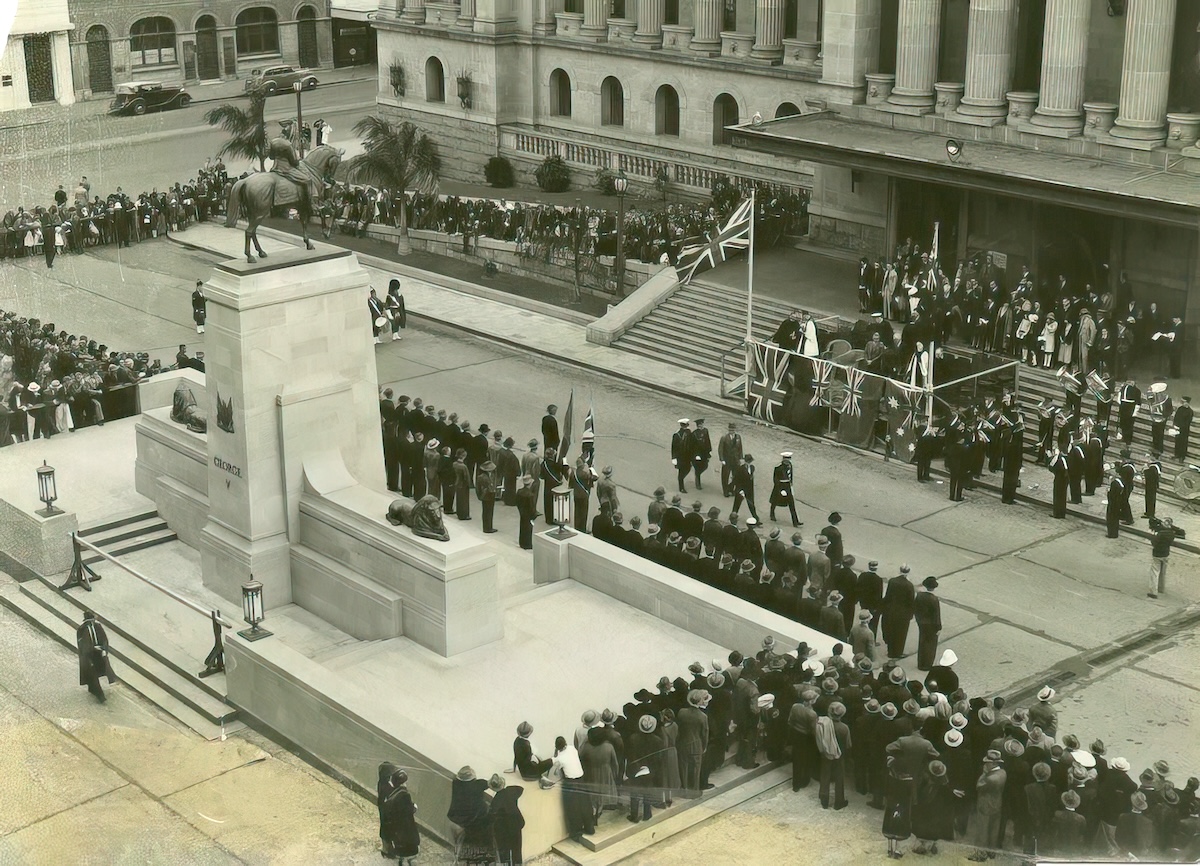

Queen Elizabeth II herself visited several times. After one visit, probably the first one in 1954, the city fathers had some ’splainin’ to do. Just in front of City Hall are two bronze lions and a statue of King George V, all part of a larger memorial unveiled in 1938 after the king's death. The statue of the king was erected facing City Hall. Upon seeing the statue, the queen is said to have been mildly annoyed, asking no one in particular, "Why is Grandpapa retreating?" Horrified, the city council realized that the statue facing the building could be seen as depicting the king retreating from an imaginary battle toward the safety of his castle. You could probably hear the barely suppressed gasps.

At the next opportunity—which wasn’t until the square was redeveloped in the late 1960s—the statue was turned around. During a subsequent visit, the queen was reportedly “delighted” with the relocation and the news that “Grandpapa” now appeared to be leading his troops into battle.

Less impressive is the famed Brisbane Door, mounted on a wall in a subsidiary corridor inside City Hall. It’s the main door from Brisbane House in Largs, Scotland, the birthplace of Sir Thomas Brisbane, the aforementioned penal colony governor. The irony is that Brisbane never, not even once, stepped foot in Queensland, let alone the city named after him.14 The door was salvaged before Brisbane House was destroyed in 1939. It seems an odd memento.

Now, let's circle back to those "structural challenges” mentioned earlier. Turns out that they built City Hall on top of a swamp. It started sinking before it was ever finished. By the 1980s, they realized they needed to do some serious restoration work. But like many things from the 1980s (looking at you, mullets and shoulder pads), the restoration didn't have real staying power.

Fast forward to 2009, when they discovered the building had more issues than a celebrity rehab clinic. Subsidence, concrete cancer, lack of reinforcing in the concrete, old wiring15—you name a structural ailment, City Hall had it. So they closed the whole place down for a solid three years and spent a cool $215 million on a complete, top-to-bottom restoration. The city held its collective breath. The grand reopening in April 2013 was probably the most exciting thing to happen in Brisbane since...well, since those two times they started building it. Or the last time they came third in something.

Brisbane City Hall has been the heart of the city since 1930. It's seen wars, floods, and probably more than a few embarrassing moments at school graduations. It's hosted rock royalty and actual royalty. It's seen the city's booms and busts from its doorstep. With its quirks and foibles, it's a perfect metaphor for Brisbane itself—grand but humble, ambitious but slightly ridiculous, and always a little rough around the edges. A testimony to the city’s unwavering commitment to being...well, third, I guess.

1. They seem loath to talk it up, but Brisbane and Queensland are #1 in one key area—the number of creative ways nature can kill you. They have the most venomous snakes, the deadliest jellyfish, the most kinds of dangerous sharks, and the greatest number of wild saltwater crocodiles. So, while they might be third in population, economics, or whatever, they’re first in their ability to make you question your every step.

Write a comment