I do love an odd museum now and again, but I wasn’t having much luck in Sydney. Maybe Sydney doesn’t have a quirky side? After several days of fruitless searching, though, I hit paydirt with a hidden gem that satisfied my craving for the off-kilter. Welcome to my totally unbiased, completely factual, and not-at-all sarcastic tour of the Sydney Masonic Centre and the Museum of Freemasonry. That’s right—a double-header!

How do you say “Freemason” in Australian?

But before we get to the building or the museum, let's take a moment to appreciate the rich history of Freemasonry in Australia. It all started in 1820 when a soldier-turned-grocer, Matthew Bacon, decided that what this penal colony really needed was a shadowy organization with secret handshakes and fancy aprons. So he rounded up two cronies from his regiment and one ticket-of-leave convict1 to found the first Australian Social Lodge.

It’s that convict that made it all work.

Samuel Clayton was a skilled English engraver and miniature painter living in Dublin. As was often the case then, this “skilled engraver and miniature painter” had a side hustle as a forger. But he got caught and was sent to Australia in 1816. His artistic talent earned him a ticket of leave, allowing him partial freedom to ply his (lawful) trade. Clayton did well and swiftly established himself as a respected engraver, painter, and printer in the burgeoning colony.2

But it was his Masonic background that truly set the stage for his colonial success. As a past lodge master back in Dublin, he was pivotal in helping Bacon and his buddies establish their Masonic lodge. Serving as Master of Ceremonies, he even designed and engraved the lodge's seal and certificates.

Thus, the first Masonic lodge in Australia was consecrated in the Golden Lion Tavern with Bacon as the Worshipful Master.3 The team grew its membership, initially seeing a 400% spike in enrollment. So, 12 members. But 12 members with a lot of get-up-and-go! This tiny lodge was the precursor for all subsequent expansion of Freemasonry in New South Wales, Tasmania, Victoria, Queensland, New Zealand, and several Pacific Islands.

From its humble beginnings in the Golden Lion Tavern, our small, ragtag bunch of apron-wearing, secret-handshake-sharing do-gooders grew like a particularly stubborn patch of kudzu. By 1877, they finally grew big enough to spring for a Grand Lodge of New South Wales.4 So they established a Masonic Hall Company and bought a little slice of Sydney real estate. In 1881, the foundation stone was laid by the Grand Master himself, Most Worshipful Brother James Squire Farnell.5

Shortly after the fancy new building opened, the local English, Scottish, and New South Wales Masonic organizations joined forces like some sort of secret society supergroup, making the new building more like the Super-Friends' Hall of Justice.

Even in their new, roomy digs, the new United Grand Lodge of New South Wales started to feel the squeeze as the years rolled by. They added two more stories just before World War I, but by the late 1930s, even that wasn't enough. After World War II, space was tighter than a Freemason's handshake. So, in 1954, they launched the War Memorial Temple Building Fund for a newer, larger lodge.

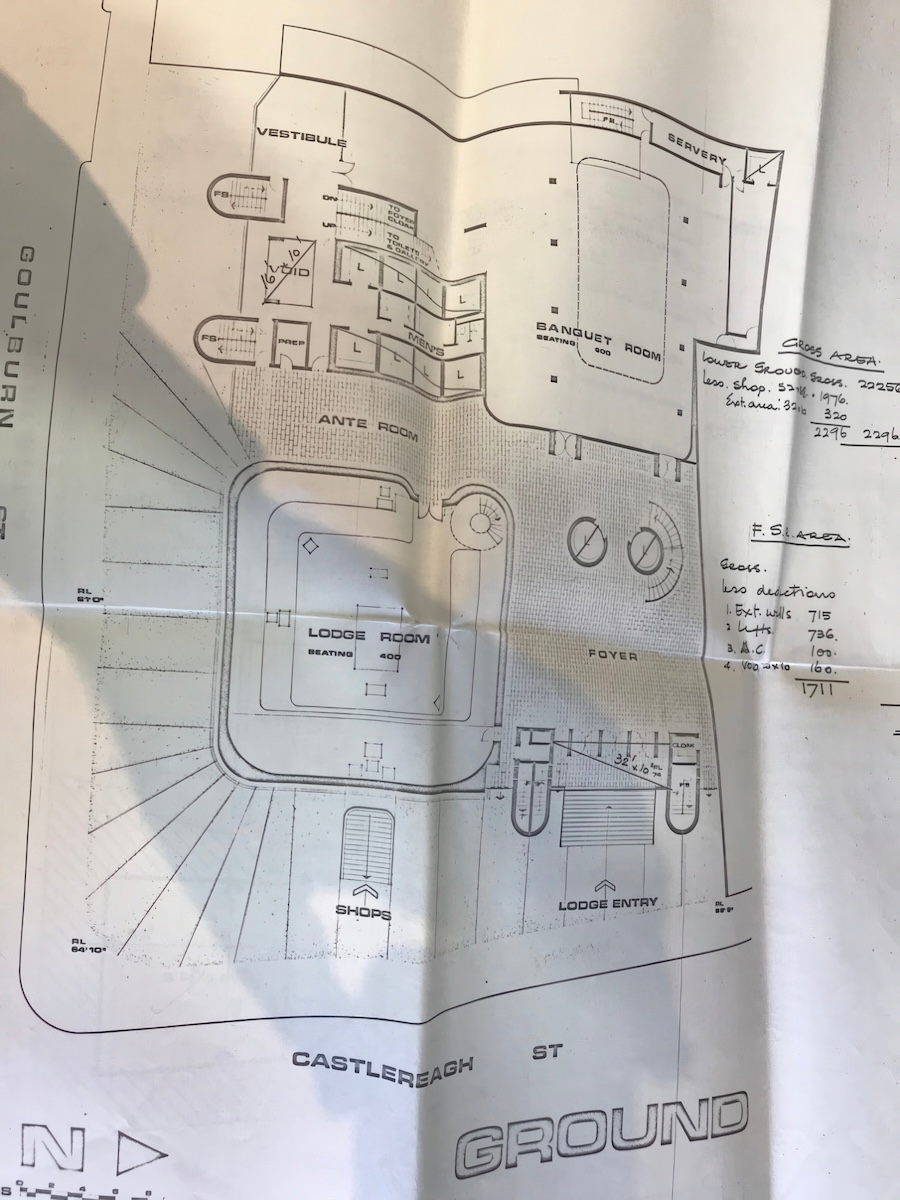

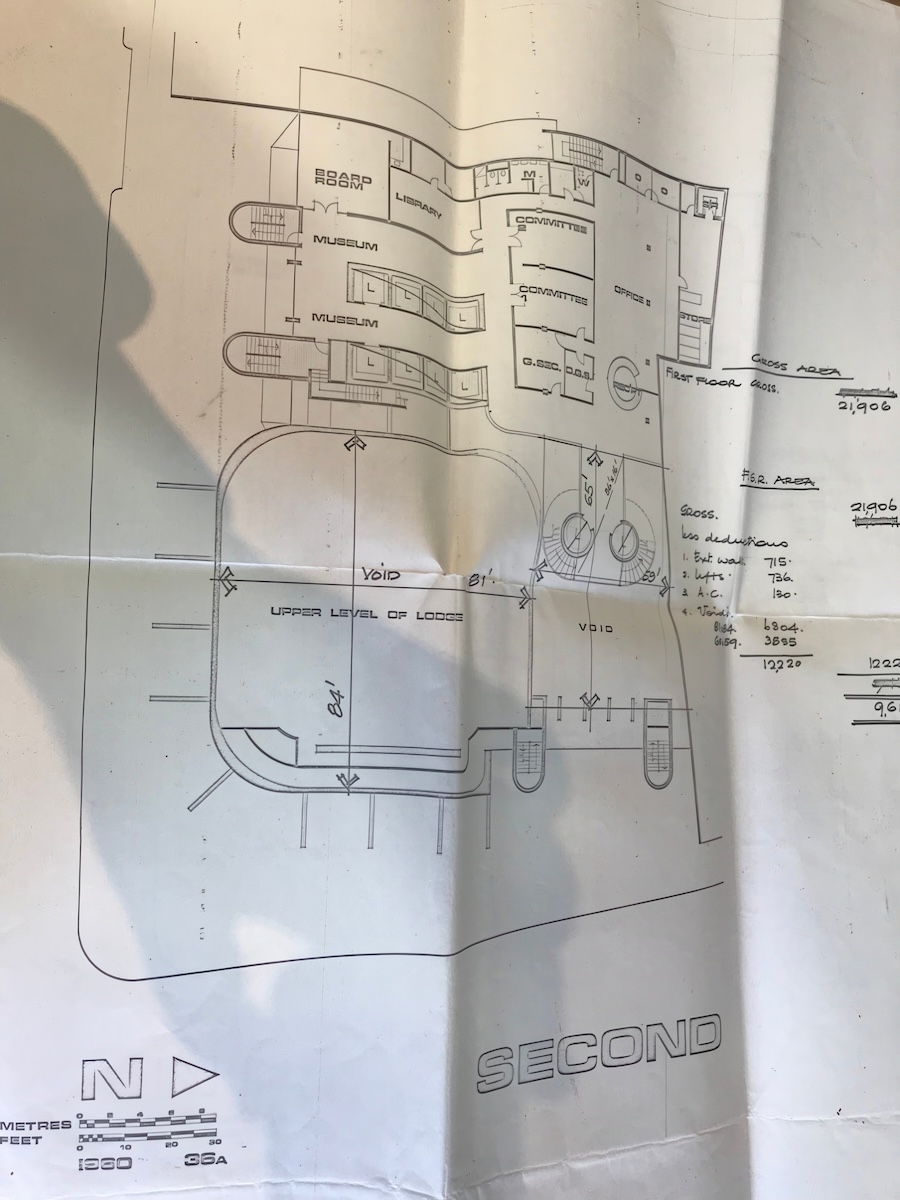

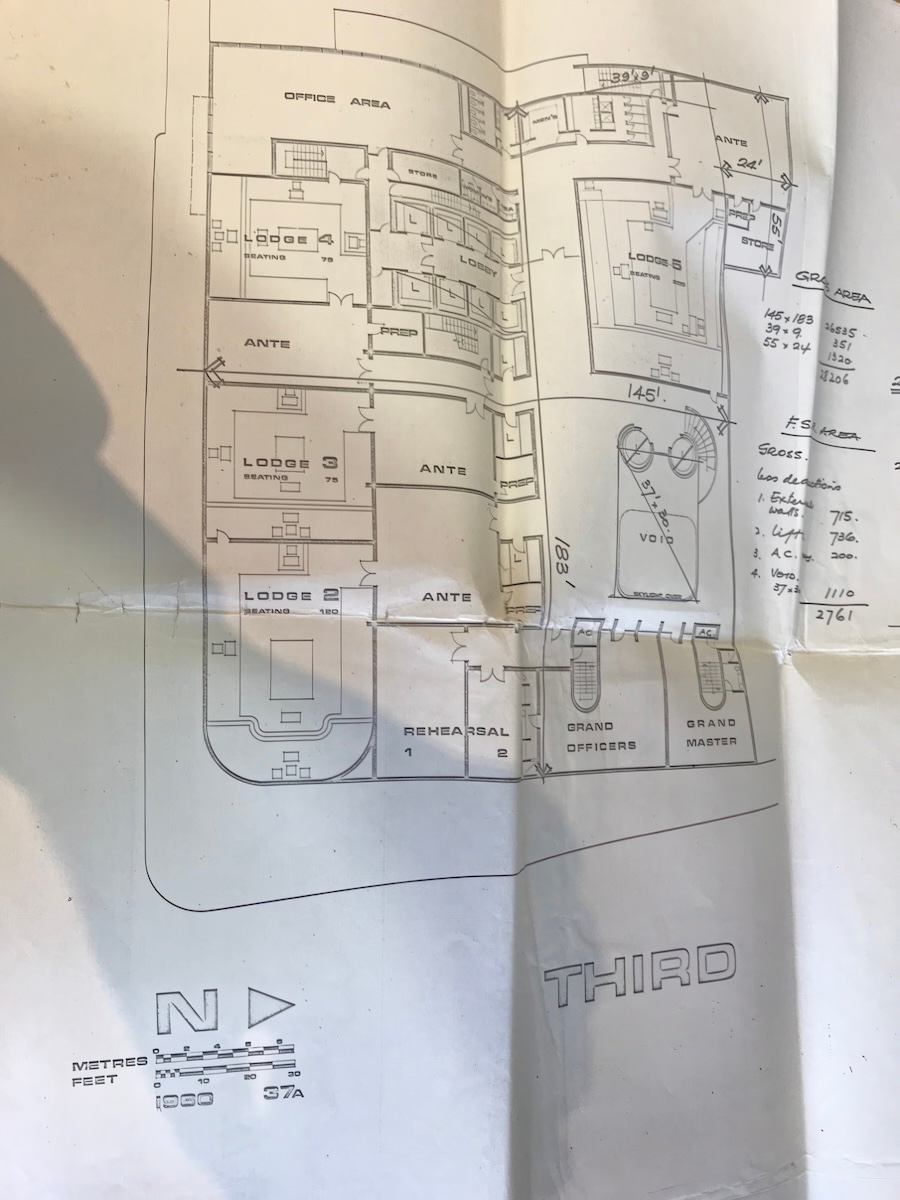

The lodge bought all the buildings and property around the Masonic Hall, tore them down, and laid (another) foundation stone in 1976 for its brand-spanking new Masonic Centre.

Brutalist beauty

Which brings us to the building part of our story.

Some might say the Masonic Centre is so aggressively ugly that it's actually beautiful. I'll admit, I have a bit of a thing for Brutalist architecture. It could be all that time I spent in a cinderblock housing project in Hungary. Or maybe the Australian sun finally fried my last functioning brain cell. But I love (most) brutalist architecture, including this building.

The Sydney Masonic Centre is a striking building that is a testament to the bold vision of 1970s architecture. Its imposing façade, crafted from raw, off-form concrete, creates a hypnotizing play of light and shadow that changes throughout the day. The building's strong geometric forms and exposed structural elements embody the Brutalist ethos of honesty in materials and function.

Inside, the sweeping curves and dramatic spaces create an atmosphere of grandeur and mystery, perfectly befitting a Masonic temple. The building's uncompromising aesthetic may not be to everyone's taste, but for those who appreciate the raw power of Brutalism, it's nothing short of magnificent.

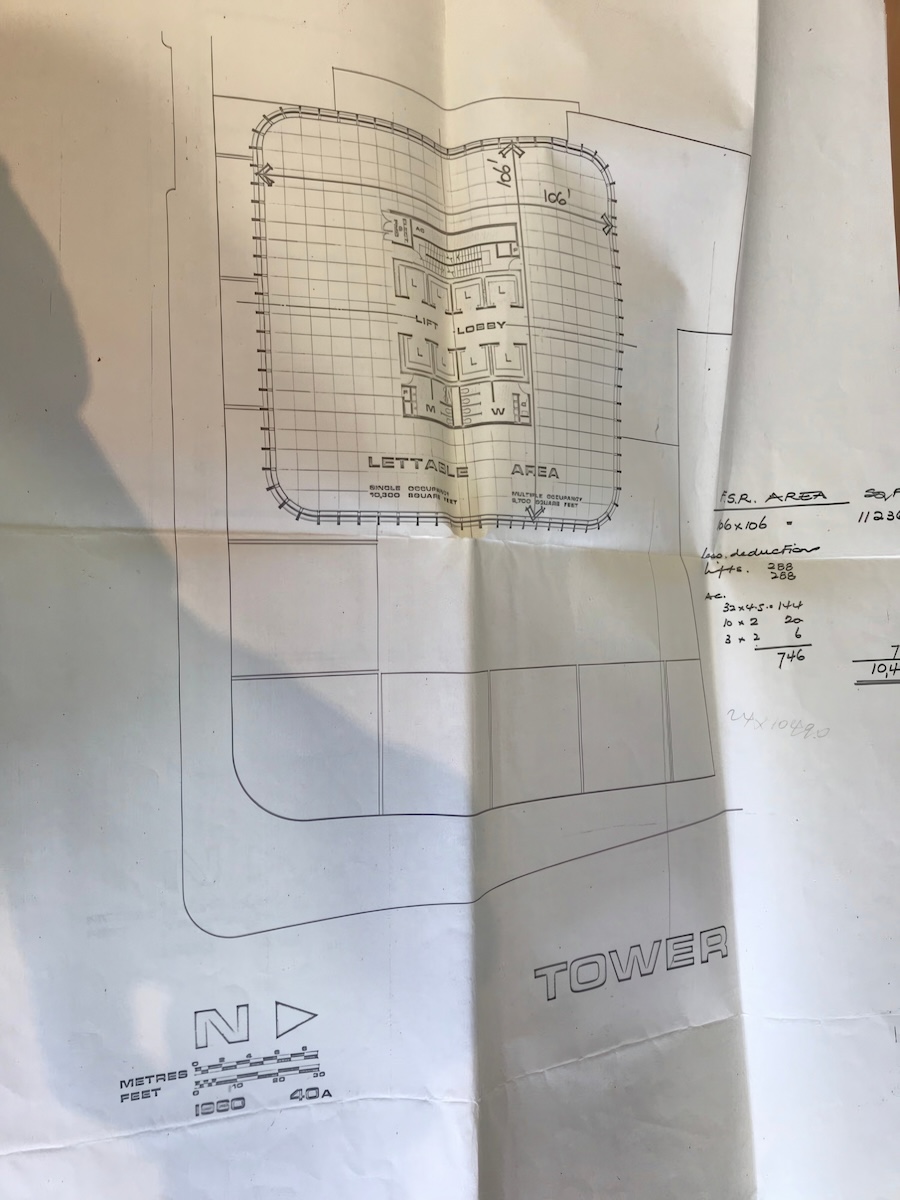

The Sydney Masonic Centre was finished in 1979 and sat alone on its corner for a couple of decades. But in 2004, it was paired with the 31-story Civic Tower that had been included in the original plans.

The tower defies gravity, appearing to balance precariously atop the original Brutalist podium. The tower's sleek glass and steel design creates a striking contrast with the robust concrete forms below, yet somehow, the two elements work in harmony.

The most impressive feat? The entire tower is supported by a central lift core, with no structural columns touching the ground—Australia’s first. This creates a visual illusion that makes the tower appear to float precariously above the podium, adding a touch of architectural magic to Sydney's skyline.6 It's the perfect blend of Brutalist brawn and modern architectural acrobatics.

Museum of mysteries

When I discovered Sydney had this Masonic temple, I immediately scheduled a tour with the curator by email. Not surprisingly, Rick elected not to join me.

When I arrived on the day of the tour, I was greeted by...absolutely no one. No front desk, no perky tour guide. Just a creepy statue of Tubal-cain hammering on his anvil.

Tubal-cain is the Freemason mascot, the biblical figure who, according to Masonic lore, was the first metalsmith. He's the patron saint of guys who spend too much time in their garages playing with power tools and dads who insist on fixing everything themselves instead of calling a professional. The Freemasons idolize him as a paragon of craftsmanship and knowledge.

The weird part? Aside from the fact that he’s theoretically working molten metal in little more than a loincloth? He’s from the Cain side of the family. Yes, that Cain—the Bible’s OG bad boy. It seems an odd choice for someone to idolize, I’m just sayin’. I’ll assume it was more about his skills than his ancestry. I'm not gonna lie, though, that statue left a poor first impression.

The place was a labyrinth of rooms, none of which had anyone in them. So I wandered around like a child in a hedge maze in The Langoliers, looking for someone, anyone. All the rooms were filled to the picture molding with paraphernalia, so it was hard to know if I was in a museum or a storehouse. I finally worked my way to the very back to an overstuffed office with one guy in it. The curator. He seemed surprised 1) to see me and 2) that I’d found him.

He did not recall our appointment, though I had his email confirmation on my phone. He told me that it’d just be a minute while he finished something really important and we could do the tour, I guess. Or I could just show myself around and let him know if I had any questions?7 His tone made it clear exactly which option he would prefer.

So I showed myself around.

Armed with nothing but my wits, good looks, and unhealthy fascination with the bizarre, I set off on my self-guided tour. I was eager to “peek into the mysteries of Freemasonry and discover an ancient yet timeless system of morality and symbols,” as promised by the website.

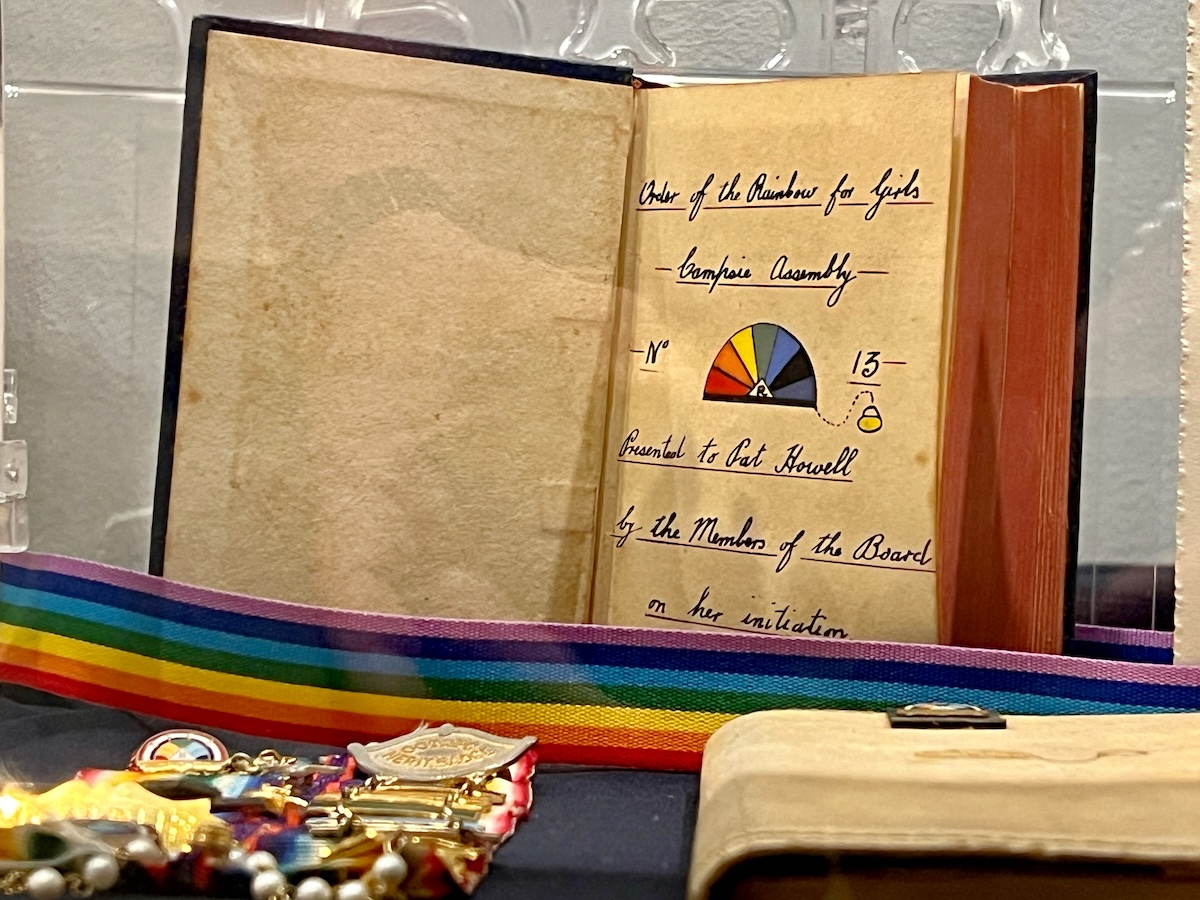

I discovered that the museum is a treasure trove of, erm, stuff. So much stuff. Glass cases filled chockablock full of stuff. Glassware, printed materials, furniture, pottery, photographs, knickknacks, regalia, ephemera, clothing—each piece carefully chosen for its deep, symbolic meaning. Or, more likely, each piece found in some dead Freemasons attic by his surviving family. Who can say?

Freemasonry has always been shrouded in secrecy and conspiracy theories. I learned through careful reading of several hand-written signs8 that the organization traces its roots to the Middle Ages when skilled masons formed groups to pass on trade secrets to their apprentices. A secret handshake identified members to one another and granted passage to secret meeting sites. Unlike other trades, masons were free to work and travel as they pleased, which is why they're called Freemasons.9

According to another sign, there are about 750,000 Freemasons in Australia and New Zealand out of about five million around the world. Um, right. Given the secretive nature of the organization and the fact that they couldn't even remember a scheduled tour, I decided to take that fact with a grain of salt.10 I reckon there are, like, maybe 45,000 in all of Australia, though that is still an alarming number of grown men willingly wearing aprons and making up silly handshakes.

Tracing boards and Gran’pop

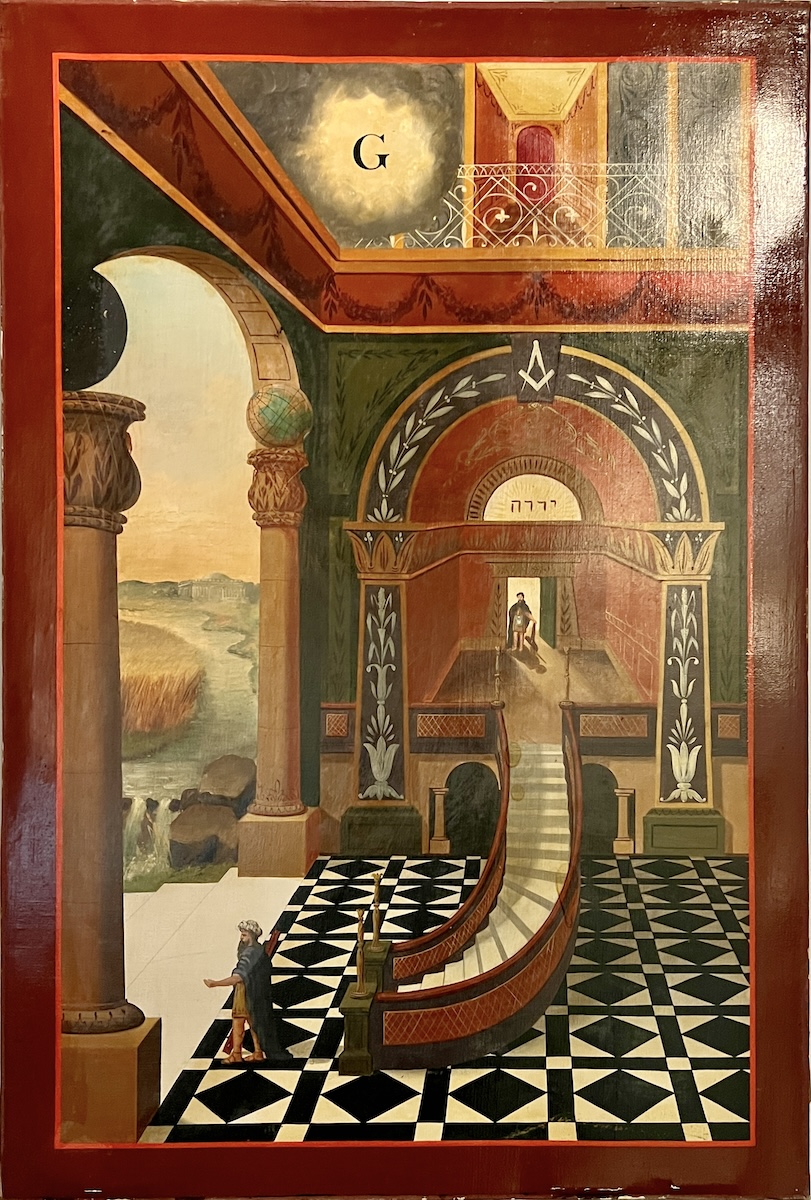

This was the first time I'd noticed tracing boards in a Freemason lodge. This one was lousy with them. Masonic tracing boards are essentially 18th-century PowerPoints with more mystical symbolism and less mind-numbing bullet points. I’m sure they have them in American lodges, too, but somehow, I missed them. Or, more likely, didn't know what I was looking at.11

Tracing boards today are painted or printed illustrations containing the various symbols of Freemasonry and are used as teaching aids—either to educate new members or to refresh older members' memories. Back in the day, when most meetings were in rooms above taverns, the images were drawn on the floor by the Tyler12—or Worshipful Master, if the lodge wasn’t big enough to have a Tyler.

They'd start with a chalked frame, inside which they'd start adding various symbols like circles, pentagrams, ladders, beehives, skeletons, etc. The boards were part mnemonic devices, part visual storytellers—memory aids for important teachings and prompts for deeper discussions—meant to help initiates navigate the labyrinth of Masonic philosophy while providing experienced members fodder for their mystical TED Talks. At the end of each meeting, the newbie would have to hang back and mop up the chalk.

Most Freemasons were loath to create permanent images of their symbology because secret! But let’s face it, making a new drawing, creating a mess, and cleaning it up Every. Damn. Time. was starting to get old. So by the mid-1700s, they’d mostly adopted modern technology—they’d throw a room-size cloth over the drawings so other tavern-goers couldn’t see them. Turns out that wasn’t a great solution because walking across the cloth would smear the chalk drawings underneath. So the Masons started painting the images on, you guessed it, boards! Boards—and canvas or even marble slabs—could be taken away. Well, and they looked way more professional.

By the 19th century, tracing boards had gone upmarket. Lodges commissioned bespoke designs like custom Masonic bling. The Picasso of the art form was John Harris, initiated in 1818. Harris churned out tracing board designs faster than you can say “square and compass.” The artistic arms race ended in 1845 when the Emulation Lodge of Improvement13 held a design competition to standardize the boards. Harris, ever the overachiever, submitted several different entries and—surprise!—won. His revised 1849 designs became the gold standard for British and Commonwealth Freemasonry.

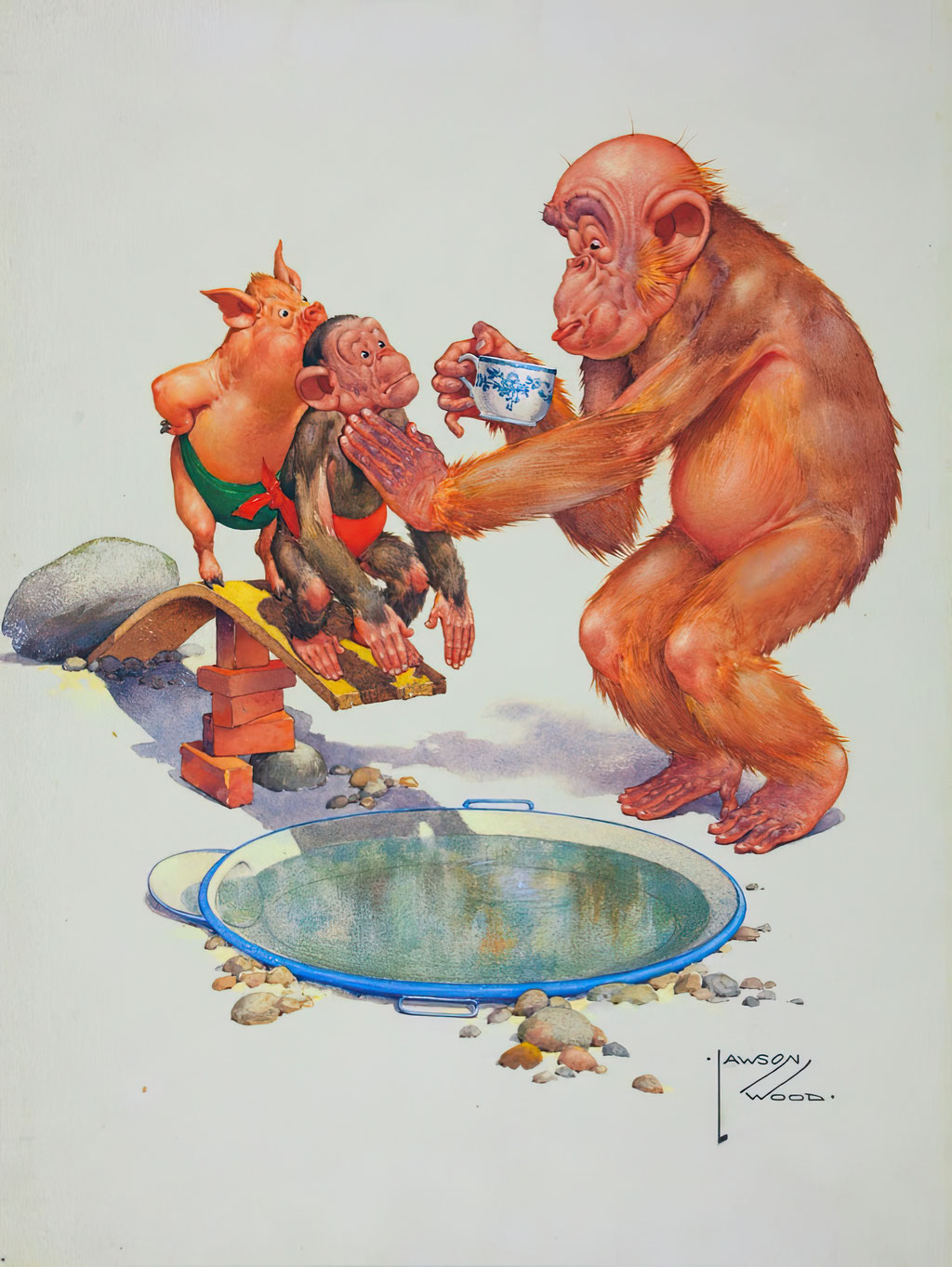

A lowbrow counterpoint to the intricate symbolism and deep philosophical meanings of the tracing boards was the Gran'pop Masonic Series. It’s, um, a bunch of propaganda cartoons about a red Freemason chimpanzee? Created by English comic artist Clarence Lawson Wood, Gran'pop is an “artful ginger ape” who gets up to Masonic mischief. These illustrations were a huge hit in Britain and Australia.14 Where tracing boards aim to educate and elevate, Gran'pop seemed determined to deflate Masonic pomposity. I mean, I didn’t think they were funny in the least, but maybe, just maybe, the Gran'pop series represents a fascinating moment when the usually secretive and serious organization became the subject of mainstream humor.15

Down another hall is the Gallery of Former Grand Masters. Picture, if you will, a hallway lined with life-sized paintings of (all white) men in elaborate costumes, ready to lead a secret ritual or audition for a community theater production of The Phantom of the Opera. The age-old tradition of immortalizing leaders in the most awkward poses possible. There's another hall filled with normal-size pictures of other famous Australians who were also Freemasons, including Tom Mix. Who is not Australian. He's from Pennsylvania.16 I was confused. But then I was cheered by a Lego model of a lodge room showing a range of very famous characters I had not known were Masons. Robin, Homer Simpson, Mr. Burns, even Yoda. Now that makes sense.

Then, honestly, I just ran out of steam. Usually, a tour guide can bring up cool no-one-else-knows-this informational tidbits, a juicy dad pun, or some unexpected insight to keep things fresh. But I'm a lousy tour guide. I didn't amuse myself at all. I loved the building, and Freemasonry seems like it might be good for some people. You know, what with the enduring nature of human curiosity and a very human desire to belong to something greater than ourselves.17 But, at its core, it was a giant concrete box filled with grown men in aprons playing an elaborate game of make-believe.

But the next time you’re in Sydney, visit the Sydney Masonic Centre and report back. Remember to take your sense of humor, appreciation for the absurd, and maybe a compass and square. What if you get initiated right there? Stranger things have happened. Probably here.

Write a comment