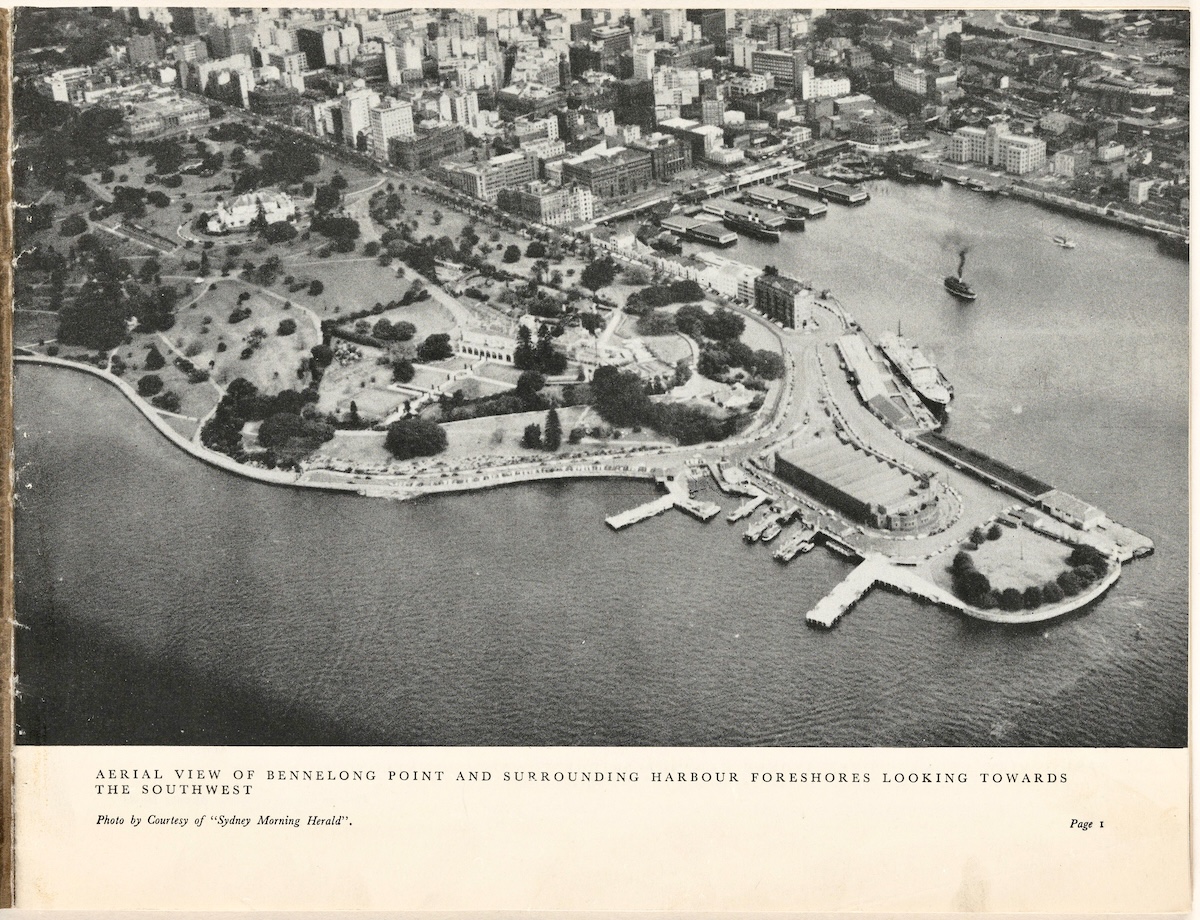

The Sydney Opera House is more than a gleaming white behemoth squatting on Bennelong Point like a cluster of half-eaten meringues—it’s the lead character in a story about architectural audacity, artistic ambition, and enough drama to fill a season of Shakespearean plays.

Sydney in the 1950s was a city on the cusp of greatness, but still searching for its identity on the world stage. Enter Sir Eugene Goossens, chief conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and man with a vision. In 1948, Goossens declared that Sydney needed an opera house. Little did he know this simple statement would forever reshape the city’s skyline and cultural landscape.

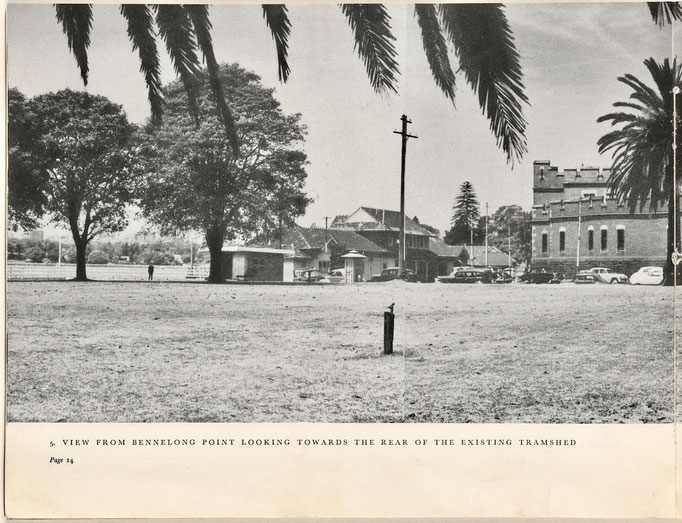

In a moment of inspired madness or visionary genius (depending on your outlook at the time), the state government agreed and immediately decided to hold an international design competition. In 1955. So, you know, seven years later, the stage was set for one of the most dramatic architectural contests in history.

The dream takes shape

Architect Jørn Utzon was working in his home office in Copenhagen when he heard about the competition. Utzon was a virtual unknown in the world of architecture at the time. He was 38 years old at the time of the competition. He’d graduated from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1942. He spent the early years of his career working and traveling, absorbing diverse architectural influences. He had very few projects with his name attached, though. The most notable were two homes—his own in Hellebæk (1952) and the Kingo Houses in Helsingør (1956–60)—which were still under construction when he submitted his Opera House design.

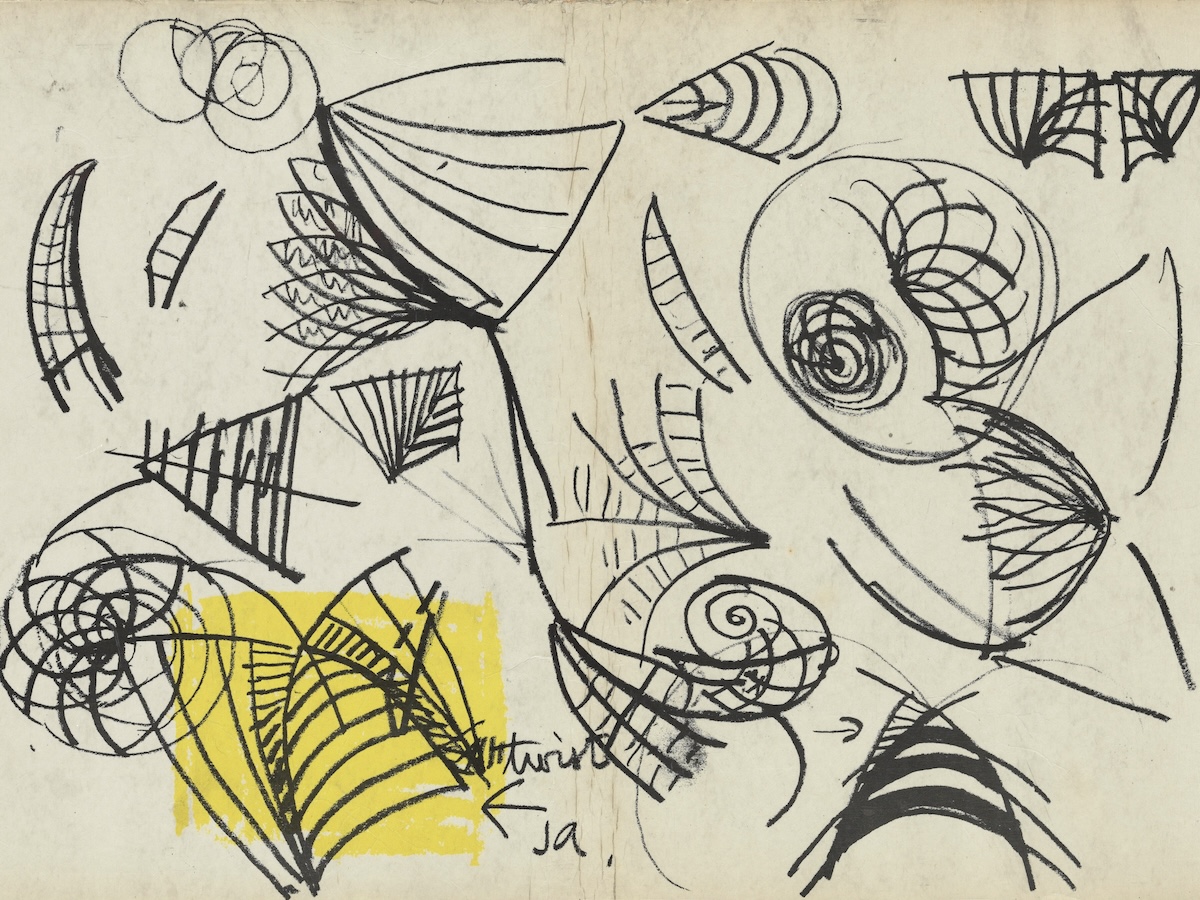

But Utzon’s professional experience included working with leading Scandinavian architects like Alvar Aalto and Arne Jacobsen. He’d also traveled to Mexico and the United States, where he was inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s organic architecture. His design philosophy was influenced by natural, organic forms, and he was fascinated by the interplay of light, landscape, and built structures. This approach, combined with his interest in platform architecture inspired by the Mayan temples he had studied, would play a crucial role in his Opera House design.

Oh, and he was a certifiable genius.

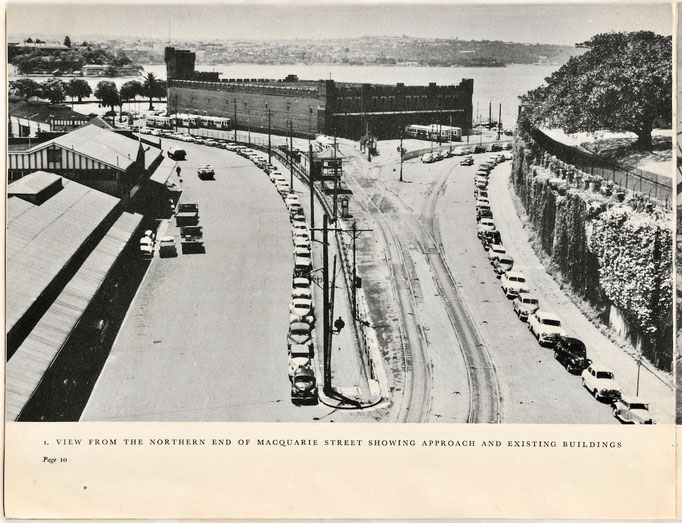

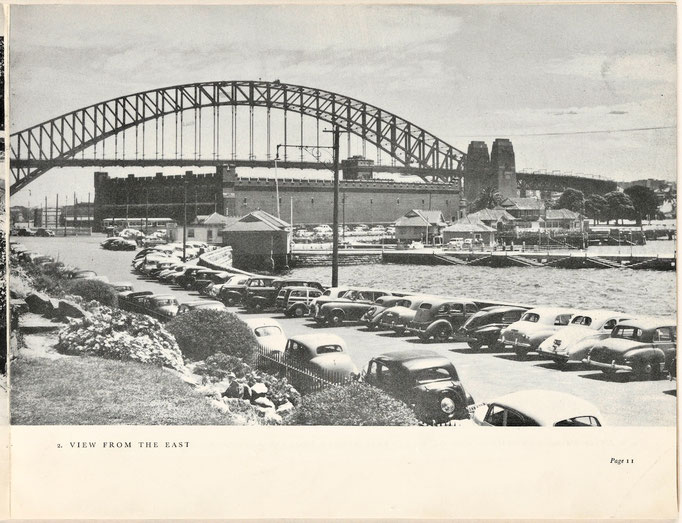

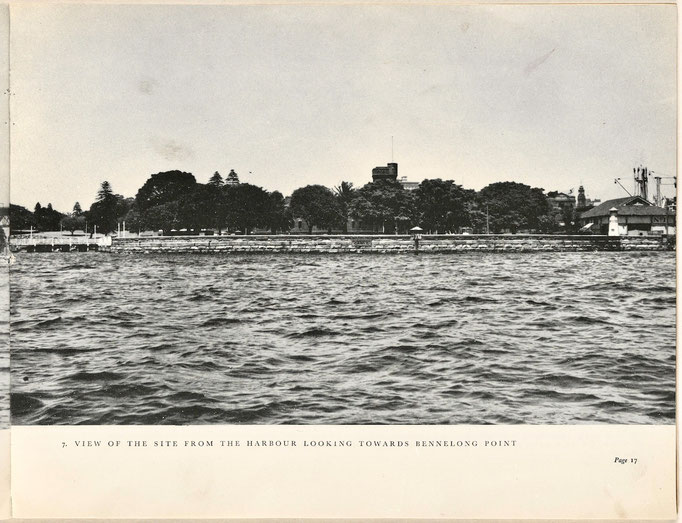

With only a few photographs of the Sydney Harbour and some rough dimensions, Utzon created a design of bold, shell-like structures rising from a massive platform. It was wholly unlike anything the world had ever seen before.

After days of scrutinizing hundreds of entries, though, the judging panel of esteemed architects and experts declared Utzon’s design “unconventional,” “too ambitious,” and “unbuildable.” They rejected it out of hand and threw it on the discard pile. But one judge walked in late, the famed Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen, whose flight from the US had been delayed.

Saarinen did not intend to rubberstamp the panel’s decisions. He insisted on seeing all the rejected designs. You can imagine the heavy collective sigh coming from the other judges, who were keen on calling it a day and heading out for a few beers. No one dared to argue with the renowned architect, though. So, as the Sydney night deepened outside, Saarinen began sifting through the discarded entries. At one point, he plucked Utzon’s proposal from the pile, declaring it the winner.

“Oh, hell no,” the other judges said.1

But Saarinen wouldn’t budge. He explained the merits of the design with the passion of the visionary he was. He pointed out its innovative approach, its harmony with the harbor setting, and its potential to become an icon not just for Sydney but for all of Australia.

The others weren’t having it. Hours passed. The night grew old as Saarinen tirelessly advocated for Utzon’s design. And he won them over. By the time the dawn crept over the horizon, skepticism had given way to curiosity—and then to excitement. The judges unanimously agreed to adopt Utzon’s proposal.

From paper to reality

Few stories are as dramatic or consequential in the annals of architectural history as this one. Utzon’s design nearly missed its moment in the spotlight but for a fluke of timing and Saarinen’s spirited defense. His victory in this prestigious international competition would catapult him to global recognition. And if you think that’s the end of the story, you don’t really know much about how long my stories can get. Nope, it was just the beginning of a tumultuous journey to follow.

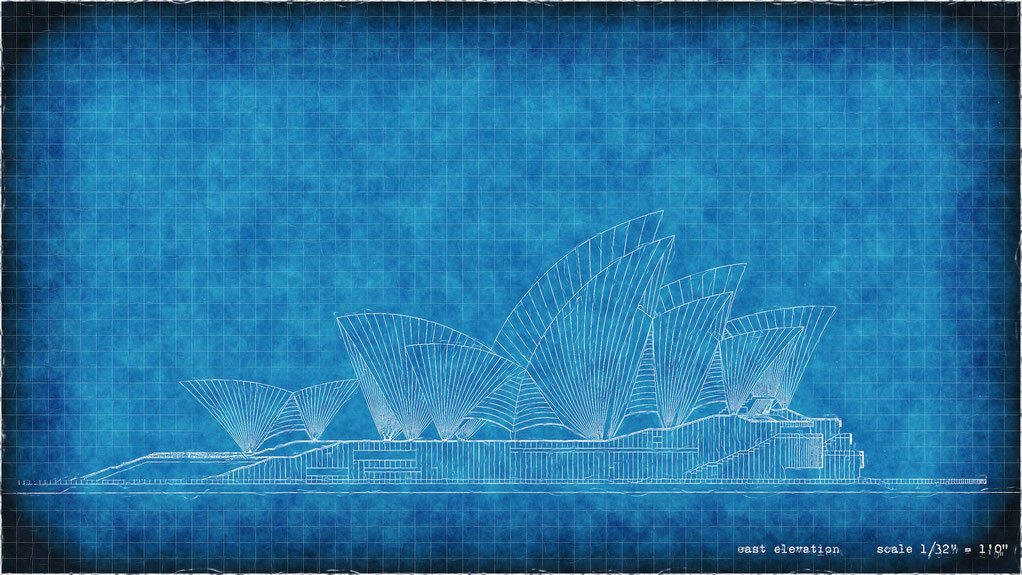

The design was, indeed, very nearly unbuildable. You think putting together an Ikea chair is hard? Hold my Scandinavian beer. Utzon’s unprecedented vision of parabolic shells with no internal support was too complicated. His practical models failed over and over again. He and his team struggled with the problem, even turning to an engineering firm, Ove Arup & Partners, for help. They explored countless mathematical models and geometric forms, but not a single one worked. And all before personal computers and AutoCAD. These poor guys were working with slide rules and giant drafting tables.

The eureka moment came in 1961 when Utzon was peeling an orange at the kitchen table, probably dejectedly. As he removed the peel in segments, he realized that all these curved segments could be extracted from a single sphere—which sparked the idea that all the shells of the Opera House could be created from sections of a sphere. And if all the shells were derived from the surface of a single sphere, they would be uniform in geometry while still appearing unique.

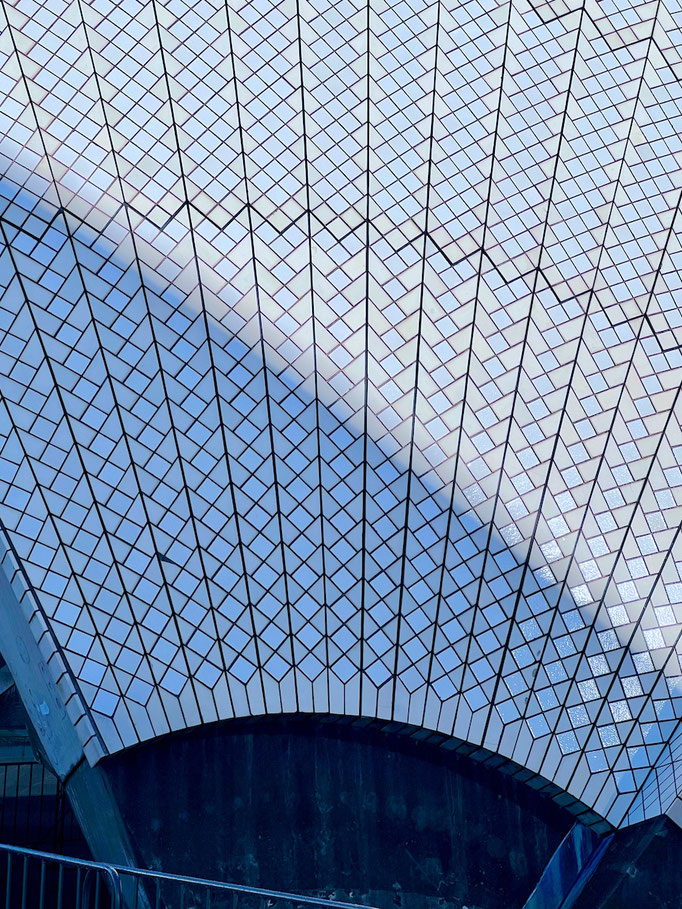

Finally! With this solution, they could move forward with construction. I mean, it was still a mathematical nightmare, but it worked!2 The roof shells, those iconic sails that make the Opera House look like a fleet of ships forever racing across the harbor, could be prefabricated in sections, assembled on-site, and covered with self-cleaning tiles custom-made in Sweden. I mean, it was doable…it wasn’t easy. Think of it as the world’s most complicated jigsaw puzzle built on 588 concrete piers sunk up to 25 meters below sea level, with roof shells covered in more than 1 million tiles arranged over 4,253 cast concrete panels.

The drama continues

But no great story is complete without a bit of drama, and the Sydney Opera House had plenty. If you’re keeping track, the entire project is now off schedule. It was also off-budget—really, really off-budget. The original estimate was for four years and $7 million. But it actually cost $102 million and took 14 years to complete.3 In the time it took to build the Opera House, we went from talking about space travel to walking on the moon.

Halfway through construction, in 1966, when the project was just seven years behind schedule, the new state government started hyperventilating about the money pit they’d inherited. They started questioning Utzon’s designs—and then stopped paying him. Utzon’s magnum opus, his symphony in stone and light, was being gutted right in front of him. Faced with an impossible situation, he resigned and left Australia, vowing never to return.

It was a divorce of epic proportions, leaving the Opera House half-built and without its visionary creator. The government brought in a team of Australian architects, led by Peter Hall, to complete the interiors. Hall was well-known, but let’s face it, it was like asking someone to finish the Mona Lisa based on one of Leonardo’s pencil sketches.4

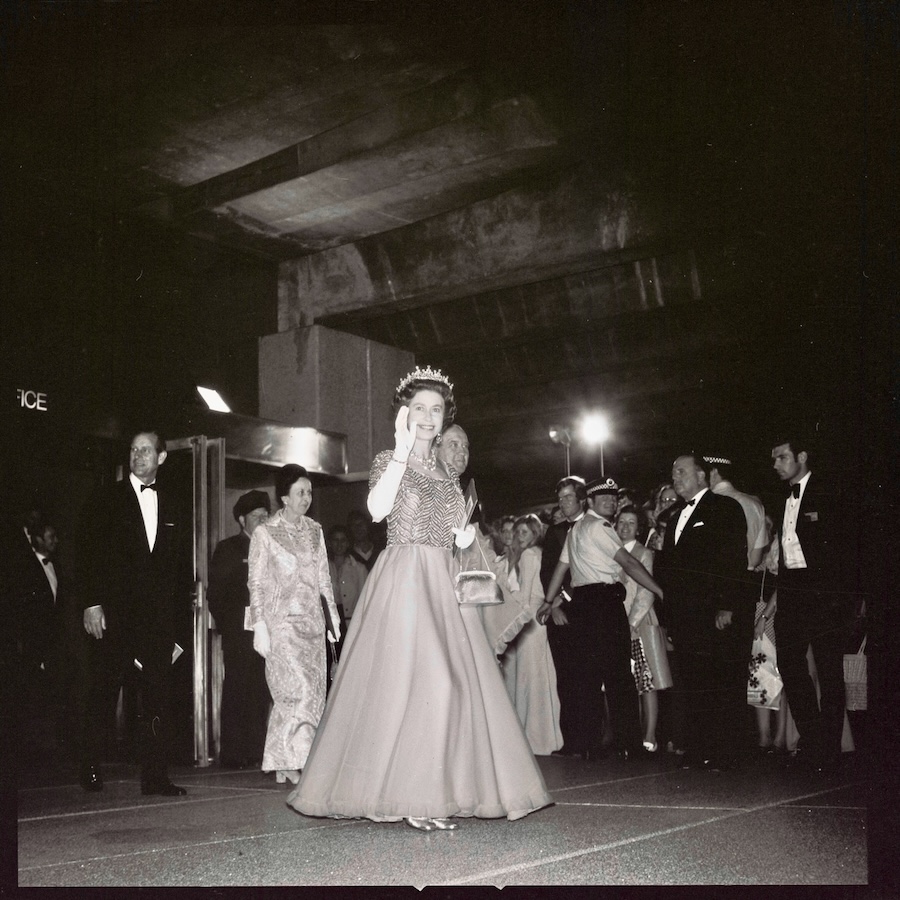

Finally, after what must’ve seemed an eternity for Sydneysiders, the Opera House was opened by Queen Elizabeth II herself in 1973. Because they were petty, the government pointedly did not invite Utzon—or mention his name.5 He never did come back to see his masterpiece before dying at the age of 90 in 2008.

A name is born

Now, when you think “opera house,” you probably think of tuxedo-clad gentlemen and ladies dripping in diamonds, sipping champagne, and discussing the finer points of Wagner.6 But the Sydney Opera House has a way more larrikin spirit about it.7 It was intended as more than just a playground for the elite from the very beginning—it was meant as a “house for the people.”

The journey began with a bit of naming confusion. When the design competition launched in 1955, the project was grandly titled the “National Opera House.” It was a name that reeked of prestige and—maybe—just a little of imperial hangover. Back in the late 19th century, slapping “national” onto the name of any cultural institution was all the rage.8 It was a trend that started to feel a bit ridiculous after Australian Federation in 1901, when places like New South Wales and Victoria became states in a larger nation.

But as the project evolved, so did its name. In 1958, Jørn Utzon referred to it as the Sydney National Opera House in his Red Book.9 By the time the foundation stone was laid in 1959, it had been streamlined to the Sydney Opera House. But for most, it was simply “the Opera House” or “the House.” Because, as any Australian can tell you, why use multiple words when one or two will do the trick?

Why call it an opera house at all? We can blame ol’ Eugene Goossens (see above) and his grand declaration in 1948. Goossens wasn’t being a diva. He used the “opera house” in an international sense—a prestigious performance venue for all sorts of cultural events. He envisioned a place that could rub shoulders with the likes of London’s Royal Opera House or San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House. These venues aren’t just for opera—they host everything from ballet to concerts to dramatic productions.10

But here’s where it gets interesting. The word “opera” in the name started to ruffle some feathers. People worried it would give the wrong impression, making the venue seem elitist and exclusive:

“

The name is a misnomer. The complex has four main performing halls, but because of its name

we will always have trouble getting this fact readily appreciated. From the start the building

was meant to be a performing arts centre, but somehow ‘opera house’ caught on

and soon became too firmly established to be changed.

—Sir Charles Moses, General Manager–ABC11

and member of the original Opera House Working Party12

”

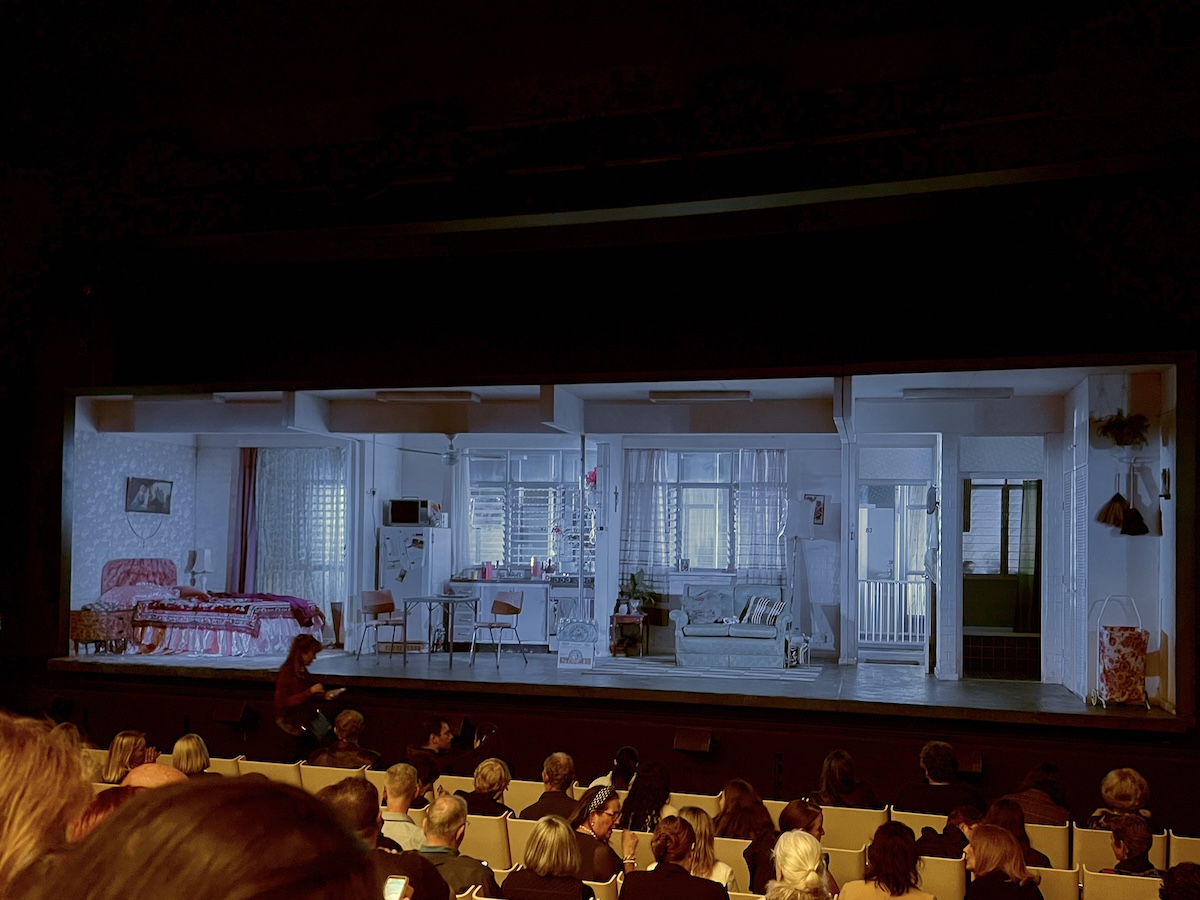

In fact, the Opera House would soon be hosting everything from classical concerts to rock shows. The Opera House Trust Act of 1961 laid out a vision for the venue that was as expansive as Utzon’s architectural plans. It was to be “a theatre, concert hall and place of assembly to be used as a place for the presentation of any of the branches of the musical, operatic, dramatic, terpsichorean,13 visual or auditory arts or as a meeting place in respect of matters of international, national or local significance.”

The real magic happened when the Opera House opened its doors, and the staff embraced the concept of public ownership and access with gusto. In the 70s and 80s, the publicity department reminded anyone who called, “It’s the people’s Opera House.”

This wasn’t feel-good marketing speak. It translated into actual policies. Anyone who could afford it could hire the theaters. The booking policy was first-come-first-served—no special treatment for the hoity-toity types. And most importantly, there was no censorship. Freedom of expression was as much a part of the Opera House’s foundation as its iconic shells.

This democratic spirit led to some unexpected events. Clifford Atkinson, a Sydney schoolteacher, called to buy a performance ticket but was mistaken to be inquiring about booking the Concert Hall. Australian to the core, he booked it for the first six Saturday nights after the Queen opened the building. With a buddy, he quickly pulled together a series of folk, rock, and jazz concerts. The gigs all sold out, and Atkinson promptly built into a successful career as a concert promoter.14

In other words, this place was never just for opera. It was a cultural smorgasbord, a venue as diverse and dynamic as Australia itself. From ballet to rock concerts, symphony orchestras to contemporary art installations and stand-up, the Opera House is a home for all forms of creative expression. Today, the Opera House hosts more than 1,500 performances a year of all types, and it’s seen the likes of Pavarotti and Prince, Ballet Russes, and Bangarra Dance Theatre.

Cultural icon

The Opera House hasn’t been without controversy, though. Some critics continue to carp that the acoustics aren't up to snuff for a world-class venue. Others complain about the irony that the Opera House’s actual opera theater (now called the Joan Sutherland Theatre) is too small for most large-scale productions. Haters gonna hate, I guess.

But these nits pale in comparison to the building’s cultural impact. The Opera House has become a canvas for public art and a focal point for national celebrations. During the 2000 Sydney Olympics, it was a centerpiece of the festivities. It stars in Sydney’s New Year’s Eve celebrations each year, fireworks cascading from its sails as the clock strikes midnight. It’s impossible to imagine Sydney—or Australia—without it.

In 2007, the Opera House received UNESCO World Heritage status, with a citation describing it as “a great architectural work of the 20th century that brings together multiple strands of creativity and innovation in both architectural form and structural design.”

As you stare up at the Opera House’s gleaming shells, it’s hard to grasp just how close this global icon came to remaining an unbuilt dream, lost in a pile of rejected proposals on a fateful night in 1957. I’m glad they plucked it out of the trash heap.

“

If we in our lifetime did nothing more than express our love of the arts by providing a building

worthy of them, even when names are forgotten, the building will always remain as a testimony

to what was done in the year 1954 by a group of citizens

for the encouragement of talent and culture.

—John Joseph Cahill, Premier of New South Wales (1952–1959)

”

Write a comment