One warm Sydney afternoon, there we were, waiting for our Uber, me with a goofy, expectant smile on my face. We were on our way to visit the Rose Seidler House, a modernist gem snuggled far from the hustle and bustle of Sydney’s city center. So far, in fact, that as the Uber driver dutifully followed the lengthy and labyrinthine route to the house, I silently worried we’d never get home.

The house is located in the suburb of Wahroonga, which, when the house was built in 1950, was even further out of town than it is today and considered downright remote. Back then, it was considered the edge of civilization, bordering the vast Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park and accessible only by a dirt road flanked by small farms and flower gardens.1 Even today, the location retains a sense of serene isolation, a stark contrast to the hustle and bustle of downtown Sydney.

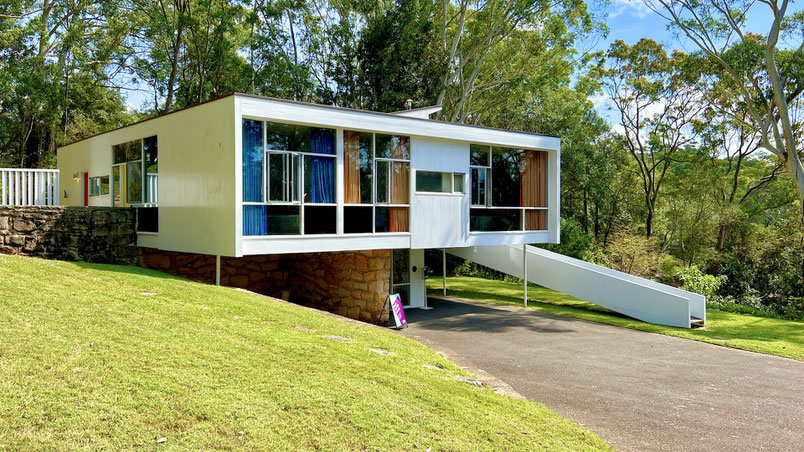

You can’t see the house from the road, so it is a delightful surprise as you walk down the drive. The Rose Seidler House is just one of three homes Harry Seidler designed for his family members on the site. He built a trio of homes so the whole family could live near each other, reuniting the family in Australia after World War II.2 The houses were designed to offer a communal living arrangement while maintaining distinct, modernist architectural features. Each is carefully situated on a steeply sloping site to maximize views while maintaining individual privacy.

As you come around the drive’s gentle curve, you see the house hovering over the rugged bushland. The stark, cube-like form of the house stood in sharp contrast to the undulating greenery around it, creating a visual tension that was captivating and serene. It felt like stepping into a 1950s sci-fi TV show.3

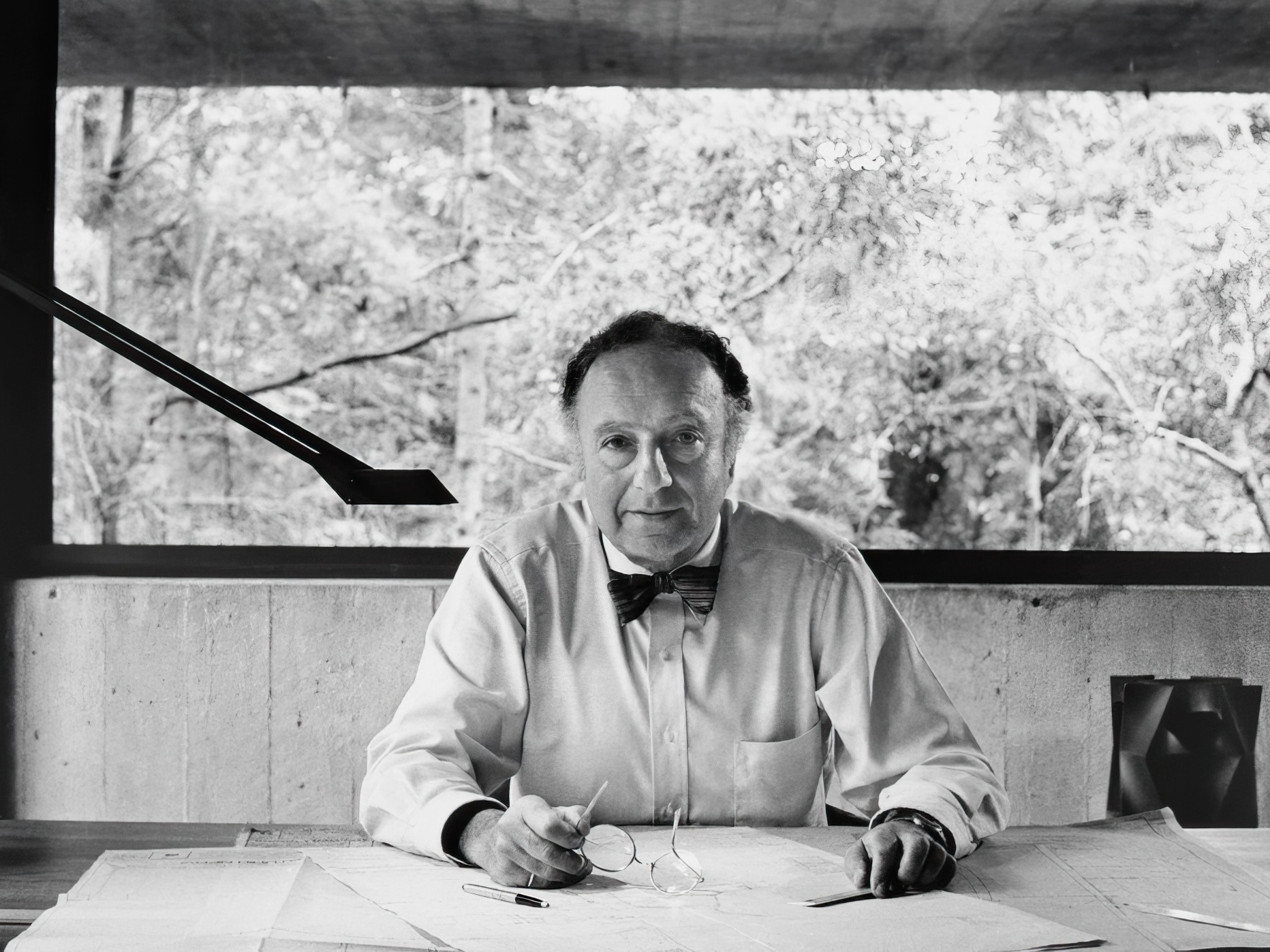

Harry Seidler was born to parents Rose and Max in Vienna in 1923. He fled to England with his brother Marcell to escape the Nazi occupation in 1938. Their parents stayed behind in Vienna but eventually made their way to Australia in the early 1940s to join Max's brother Marcus, who had established a successful shirt-making business in Sydney.

The boys’ journey took them through internment as “enemy aliens” in Canada, where Harry’s architectural journey began at the University of Manitoba. His studies continued at the Harvard Graduate School of Design under the mentorship of Walter Gropius, a founder of the Bauhaus movement. Seidler’s vision was further shaped by his work with Marcel Breuer and his time in Brazil, where he absorbed the modernist influences of Oscar Niemeyer and Lúcio Costa.

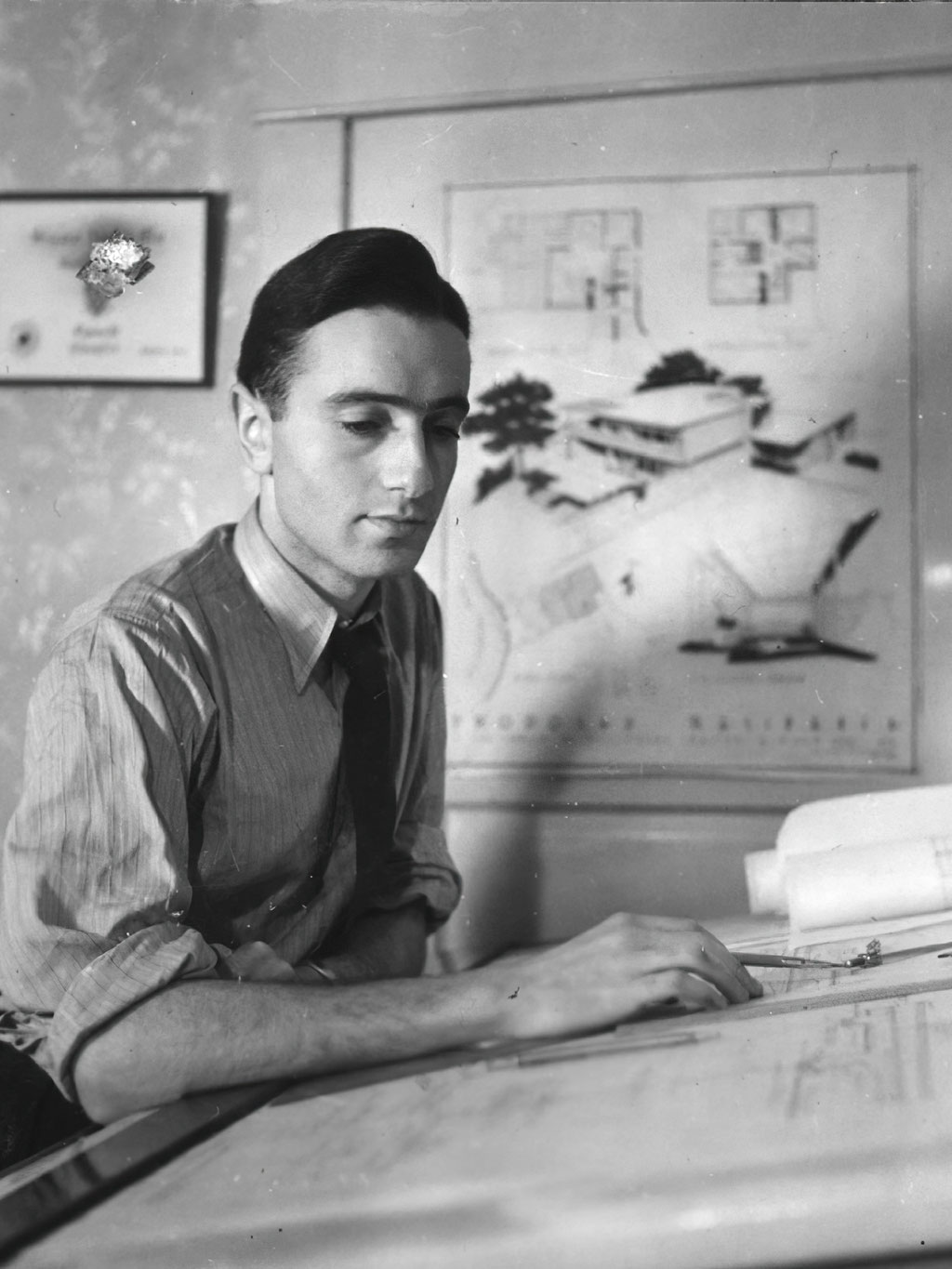

When Harry arrived in Sydney in 1948, he brought with him a radical vision that upended the local architectural scene. At the time, Sydney was just emerging from a period of austerity and embracing a newfound optimism. The city was ready to shed its post-war drabness for a brighter, more modern future. Enter Harry Seidler, the modernist wunderkind, fresh off the boat from New York via Brazil, with a head full of radical ideas.

The house for his parents was his first Australian commission and his chance to make a bold declaration of modernist principles that emphasized simplicity, functionality, and a harmonious relationship with the natural environment. Seidler’s design for the house was revolutionary, overturning the standing convention of domestic Australian architecture.

When the design for his parents' home hit the scene, Sydney collectively inhaled sharply and held its breath. Most fancy homes built then were traditional and conservative,4 emphasizing a homely aesthetic that featured pitched roofs, brick exteriors, bay windows, and ornamental details. Seidler’s floor plan was something wholly new, with the house divided into distinct living and sleeping zones connected by a central playroom, stairs, and terrace. Rather than facing the street, the house sat back from the road in the center of its wild lot. Instead of conventional walls, Seidler used flexible dividers and sliding doors, creating a dynamic, adaptable living space.

Seidler’s vision left the traditionalists clutching their pearls. It was, they said, “the most talked about house in Sydney” when it was finished in 1950.

Seidler’s approach was as holistic as a yoga retreat. He didn’t just design walls and roofs—he crafted an entire living experience, right down to the furnishings and the landscaping. The house was his canvas, and boy, did he paint a picture that Sydney wouldn’t soon forget.

“

When designing a house, the contemporary architect thinks of an

‘environment for living’ rather than of empty box-like

rooms...he designs actual spaces in the interior

for specific purposes and designs the furnishings

and equipment that go into them.

—Harry Seidler, 1952

”

I was so excited about seeing this place that I scheduled our visit before locking down our Airbnb in Sydney. Priorities, right? But hey, sometimes you just have to follow your architectural heart. As we wandered through the neatly designed rooms, it was clear why Seidler’s vision was both celebrated and controversial. The open-plan living areas, floor-to-ceiling glass windows, and minimalist design were light-years ahead of the time. Each room, bathed in natural light, offered panoramic bushland views, making it feel like you’re in a luxurious treehouse.

Of course, me being me, I made a beeline for the kitchen. And oh my gosh, what an amazing place. A masterpiece of mid-century modern design. Rose was known to be a superb cook and hostess, and, in 1950, her kitchen was considered one of the best-equipped in Australia. Imagine stepping into a space straight out of The Jetsons. This kitchen was ahead of its time, featuring a waste disposal unit, the latest refrigerator model, stove, dishwasher, exhaust fan—and even a Mixmaster. It was a dream come true for any mid-century housewife or cooking enthusiast.

Harry Seidler’s belief that “the relation between the kitchen work center and the dining room table must be an arm’s length matter” was brought to life with a counter that acted as a pass-through and could be shut off from the dining room by a sliding panel. Today, we take this type of thing for granted. But back then, it was ground-breaking. This ingenious design facilitated easy serving and kept the kitchen separate when needed, maintaining the sleek, uncluttered look of the dining area.

Seidler didn’t stop at the appliances. The kitchen featured built-in shelving and storage designed for maximum efficiency and minimal clutter. The cabinetry was sleek and modern, with clean lines and functional design. And the color! Awesome. Every utensil, every gadget, had its place. The kitchen's aesthetic was completed with industrial-designed items like the Gents plastic wall clock and the Flint utensil set, making it a place to cook and showcase modern design.

Seidler was so committed to his modernist aesthetic that he also selected the crockery (minimalist), cutlery (contemporary), and glassware (unadorned)—and he made his mother get rid of all her traditional Viennese silver, china, and crystal. Rose largely embraced her son's modernist vision for the house but kept a few cherished pieces, like her ornate silverware and a fancy tea set. Seidler designed a special “traymobile” to Rose’s specifications to display her tea set.5

When I’d had my fill of the kitchen, I moved on to the rest of the house, starting with the living room. The open-plan design allowed for a seamless flow of space, with floor-to-ceiling windows that brought the outside in. The furniture in the living room was a mix of pieces sourced from the New York showrooms of Herman Miller and Knoll, along with custom pieces designed by Seidler himself. The coffee table, the traymobile, and the sofa were all designed to fit perfectly within the space, both in terms of aesthetics and functionality. Seidler’s design philosophy was evident in every piece—everything was there for a reason, and nothing was superfluous.

A standout feature was the built-in stereo shelving with a vintage radio and phonograph. The phonograph, state-of-the-art at the time, allowed the Seidlers to enjoy their favorite records with unparalleled sound quality. The built-in shelving provided storage for their record collection, keeping everything neat and organized. It was a perfect blend of form and function, showcasing Seidler's attention to detail and commitment to creating spaces that enhanced the quality of life.

Like the rest of the house, the bedrooms were designed with both aesthetics and functionality in mind. The sleeping areas were separated from the public spaces by a central playroom, stairs, and a terrace, creating distinct zones for different activities. Inspired by Marcel Breuer, this “binuclear” floor plan allowed for flexibility in how the spaces were used.

Each bedroom featured built-in wardrobes and sliding doors, maximizing space and creating a clean, uncluttered look. The design was minimalist but comfortable, with lightweight furniture that was easy to move and rearrange. Large windows offered stunning views, making each room feel like a private retreat.

The outdoor areas of the house were as thoughtfully designed as the interior. Rose herself contributed significantly to the landscaping, transforming the rugged bushland into a series of rockeries and gardens. The lawn area, surrounded by exotic plants, fruit trees, and vegetable gardens, provided a perfect setting for outdoor entertaining and relaxation.

The terrace, accessible from multiple rooms, was an extension of the living space, allowing the family to enjoy the outdoors without leaving the comfort of their home. The design blurred the lines between indoor and outdoor living. This concept was ahead of its time and has since become a staple in modern architecture.

Rose and Max Seidler moved into their new home in late 1950, and life was anything but ordinary. Reactions to the house were a mix of awe, admiration—and bewilderment. Extensive media coverage meant that on weekends, the driveway would be lined with curious onlookers, pressing their noses against the glass walls, peering in.6

Of course, not everyone was a fan. A lot of people probably thought Seidler had lost his mind. Some were fascinated by the house’s modernity, while others were puzzled by its stark departure from the norm. The local council was just looking for ways to nip it in the bud.

“

[The local council] said, ‘You’ve got two bathrooms and only one

of them has got a window.’ I said, ‘No, that’s not right, they

both have windows.’ ‘Where’s the window, where’s the window?’

You explain the plan to the local building inspector, he didn’t realize there

was a window sticking out of the roof on top—a skylight.

‘Oh is that it?’ He was trying to find rules that forbid that

kind of thing...but he didn’t get very far with me, so it got approved.

—Harry Seidler, 2003

”

But as history would show, Seidler was not just ahead of his time—he was setting the stage for a new era of Australian architecture.

Visiting the Rose Seidler House was like stepping into a time capsule of modernist design. It was a reminder of the boldness and vision of architects like Harry Seidler, who dared to challenge conventions and reimagine how we live. As I stood there, waiting for my Uber, I realized that Seidler’s legacy was not just in the buildings he designed but in how he inspired us to think differently about our spaces and lives.

Of course, as I’d suspected, getting back to civilization required more than just a little luck. But as I stood by the road, waving my phone in the air to somehow boost reception, waiting for a ride, I couldn’t help but chuckle at the irony—here I was, at the intersection of past and future, in a house that redefined modern living, yet utterly reliant on the whims of a fussy rideshare app and poor cell service.

So for all you budding architects with pioneer spirits out there, when designing the Home of Tomorrow, always make sure there’s good wifi—because you never know when you’ll need to call an Uber.

The Marcus Seidler House, finished in 1953, is a suspended cube with exposed elements inside and out, a continuous terrace on the north side, and a central open well for light. This home represents Seidler’s commitment to pulling sunlight into the living space.

The Julian Rose House, completed in 1954, is more structurally daring. Its elevated main floor is supported by a double cantilevered steel frame. It includes floor-to-ceiling windows and sliding doors facing the northern view, a freestanding fieldstone fireplace that floats in the living area, and a compact kitchen inspired by the model kitchen design developed in 1926.

All three houses, set in a wooded area with distant landscape vistas and a private driveway, showcase Seidler’s vision of modernist family compounds, blending architectural innovation with natural surroundings.

Write a comment