Buried in the back streets of Surry Hills, a suburb of Sydney, lies Brett Whiteley’s last home and studio. Presumably. The street grid was clearly designed by a city planner with a fear of symmetry and right angles.

But after hours of wandering, we did indeed find it.1 Outside, it was a nondescript brown building that looked about as exciting as a tax return. It didn’t seem like the studio of one of Australia’s most celebrated artists. But it was.2

Inside, it was definitely not nondescript. The first floor is very gallery-like, so a good beginning. But Rick and I always like to start at the top and work our way back down.3 And upstairs here is like being inside the mind of a mad genius.

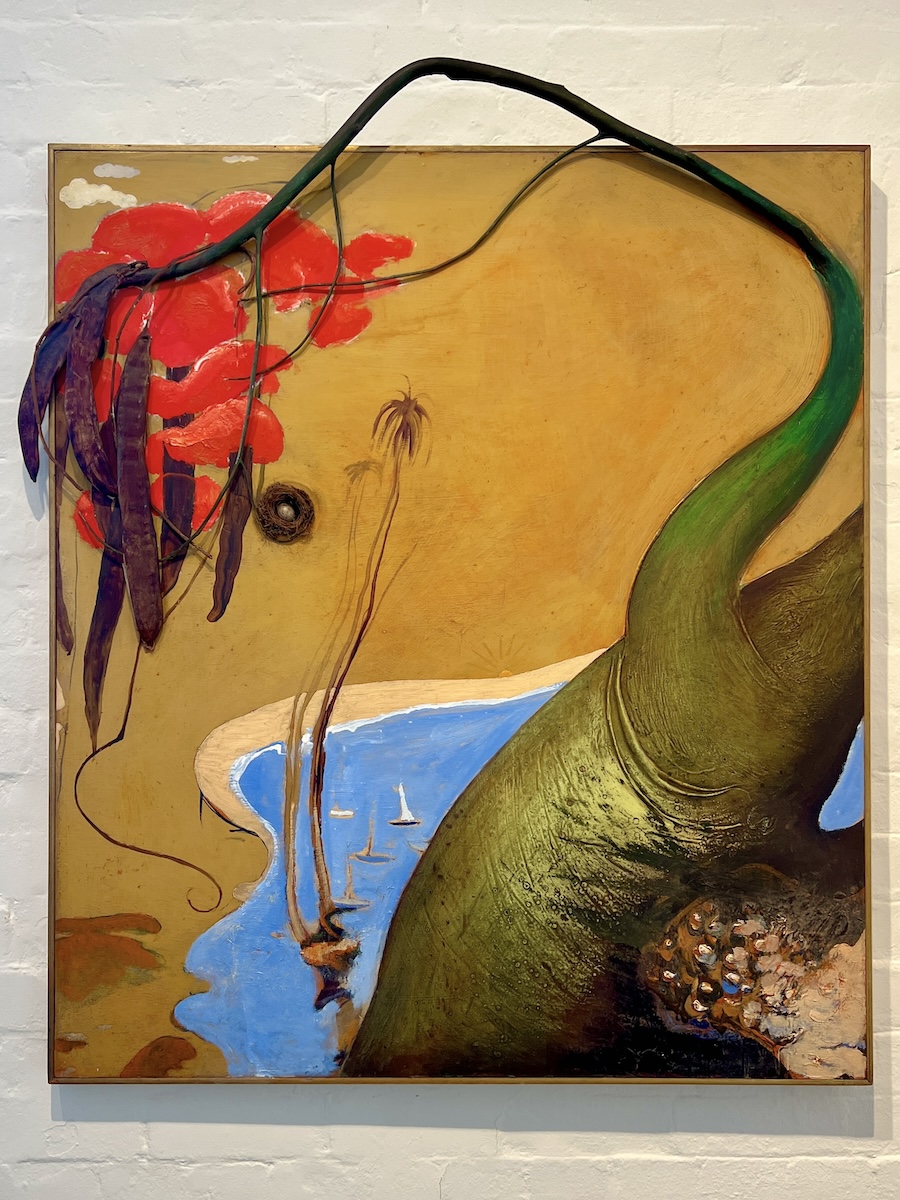

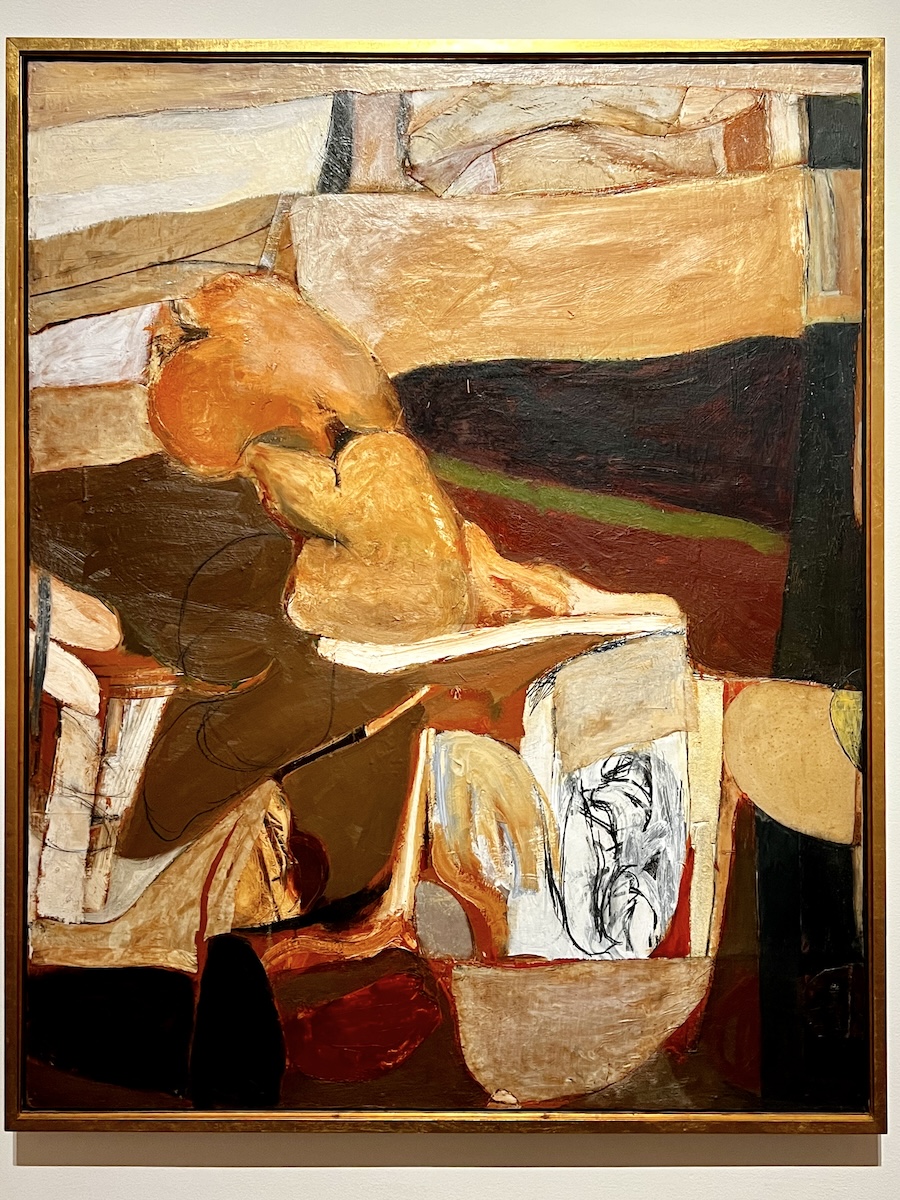

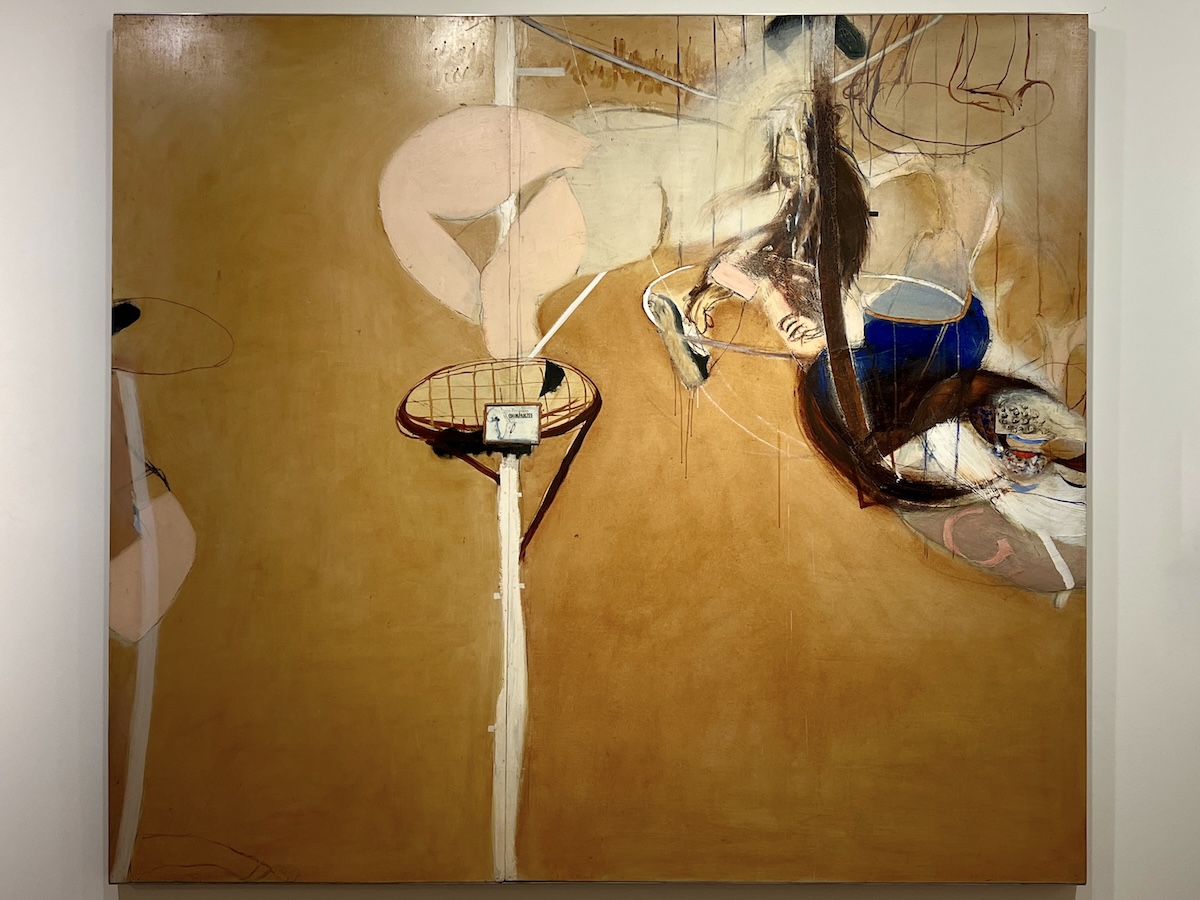

The space was a chaotic symphony of colors, textures, and objects. Unfinished canvases casually leaned against walls, half-formed images teasing the imagination. Finished paintings—a couple quite famous ones, even—were hung more formally on the whitewashed brick. Abstract constellations of paint splatters on the floorboards. Ephemera piled tall and neat. Art supplies cluttering the studio floor a little less tidily.

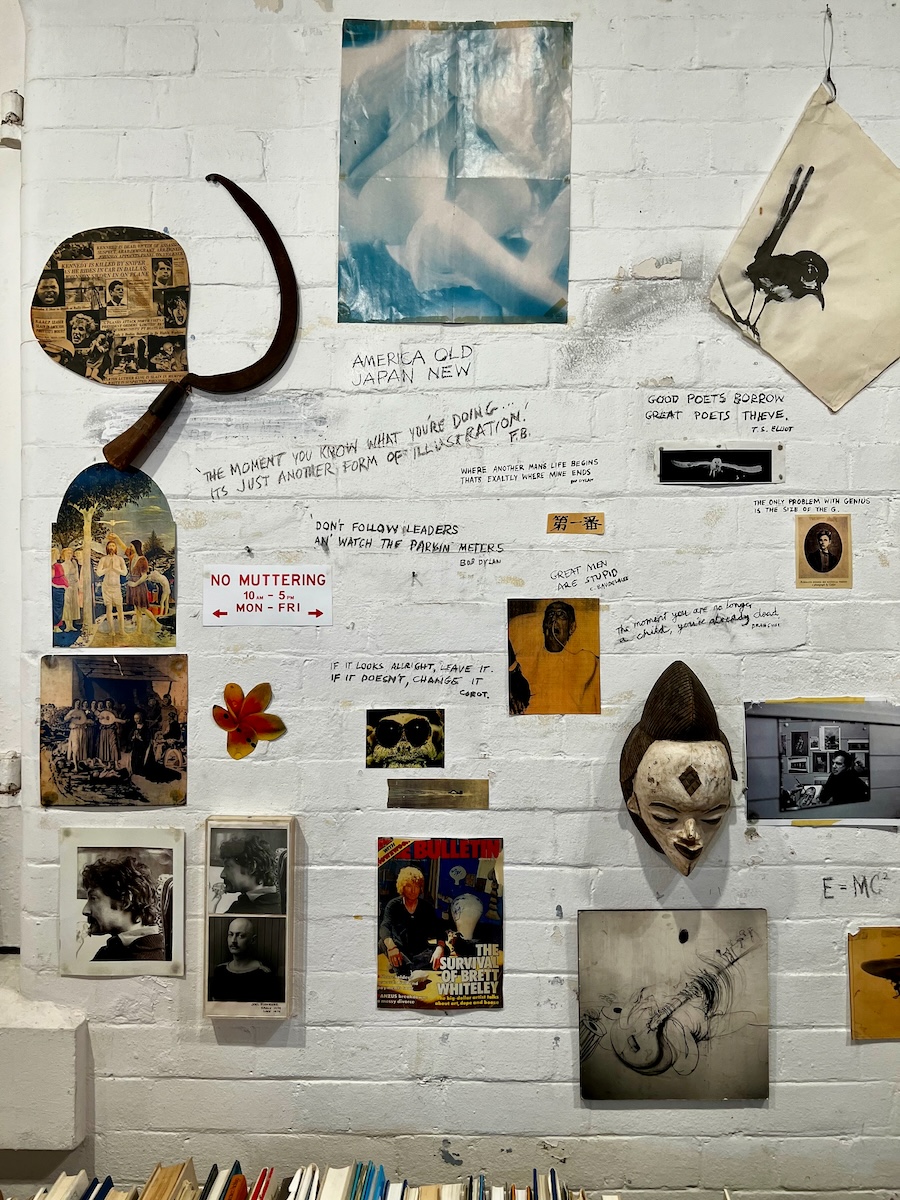

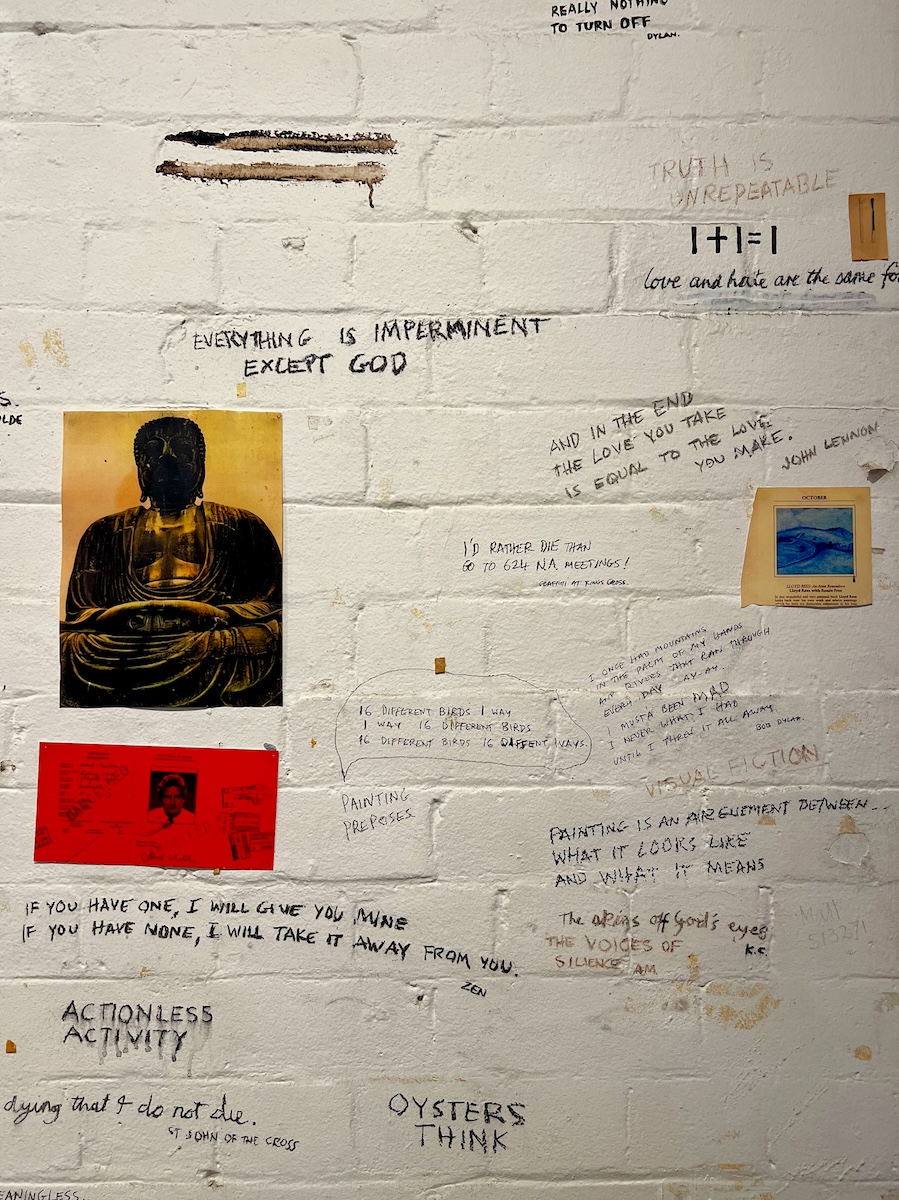

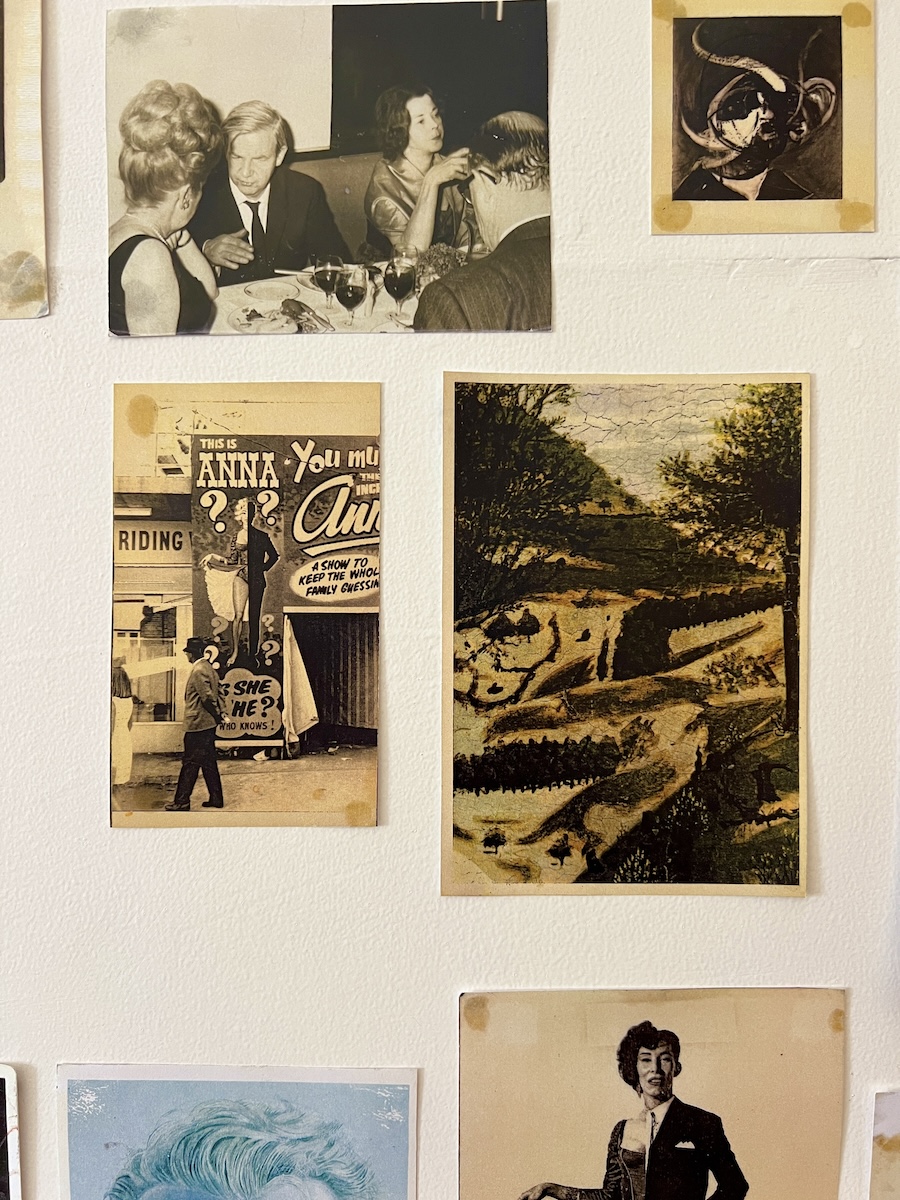

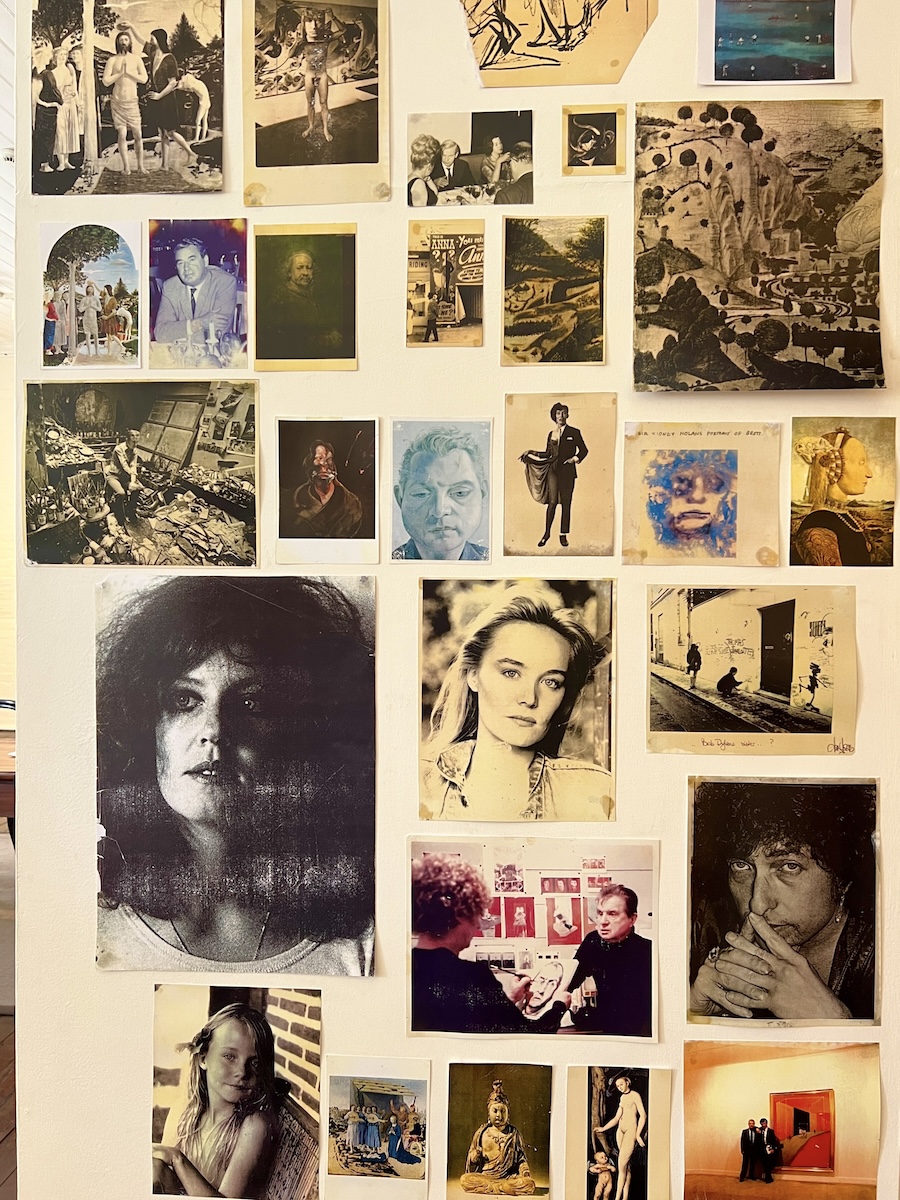

One wall was covered in handwritten quotes, taped-up clippings, and photos. Like the world’s most artistic bathroom stall, minus the crude drawings and phone numbers.4 Turning the corner, though, I found the phone numbers scrawled on the wall above his telephone table. Oh, how I wanted to see if any of them still worked. Don’t worry. I didn’t embarrass America.

Poking around felt a bit like snooping through someone’s diary5—someone who was a wildly talented, slightly unhinged artist with a penchant for collecting oddities. Shells, seed pods, binoculars, and even a cricket ball were scattered about, each object presumably holding some profound artistic significance that was entirely lost on me. Or maybe he just liked them.

The air was thick with the ghosts of creativity past, and I could almost hear the echoes of ‘60s rock music that once filled these walls.6 The space was littered with paintings from Whiteley’s time in London, New York, and Fiji.

Whiteley was a born and raised Sydneysider. He went to art school here. But in 1959, at the age of 20, he earned an Italian art scholarship and couldn’t leave fast enough. He landed in London in 1961, where he met Wendy Julius, a fellow Australian who became his wife, muse, and partner in chaos. Their marriage, a whirlwind of paint fumes and passion, produced countless artworks and a daughter, Arkie, born in 1964. In London, among other things, Whiteley created several paintings of animals at the London Zoo, which he felt was a particular challenge—not only because the animals keep moving, but because it was “sometimes painful to feel what one guesses the animal ‘feels’ from inside.”

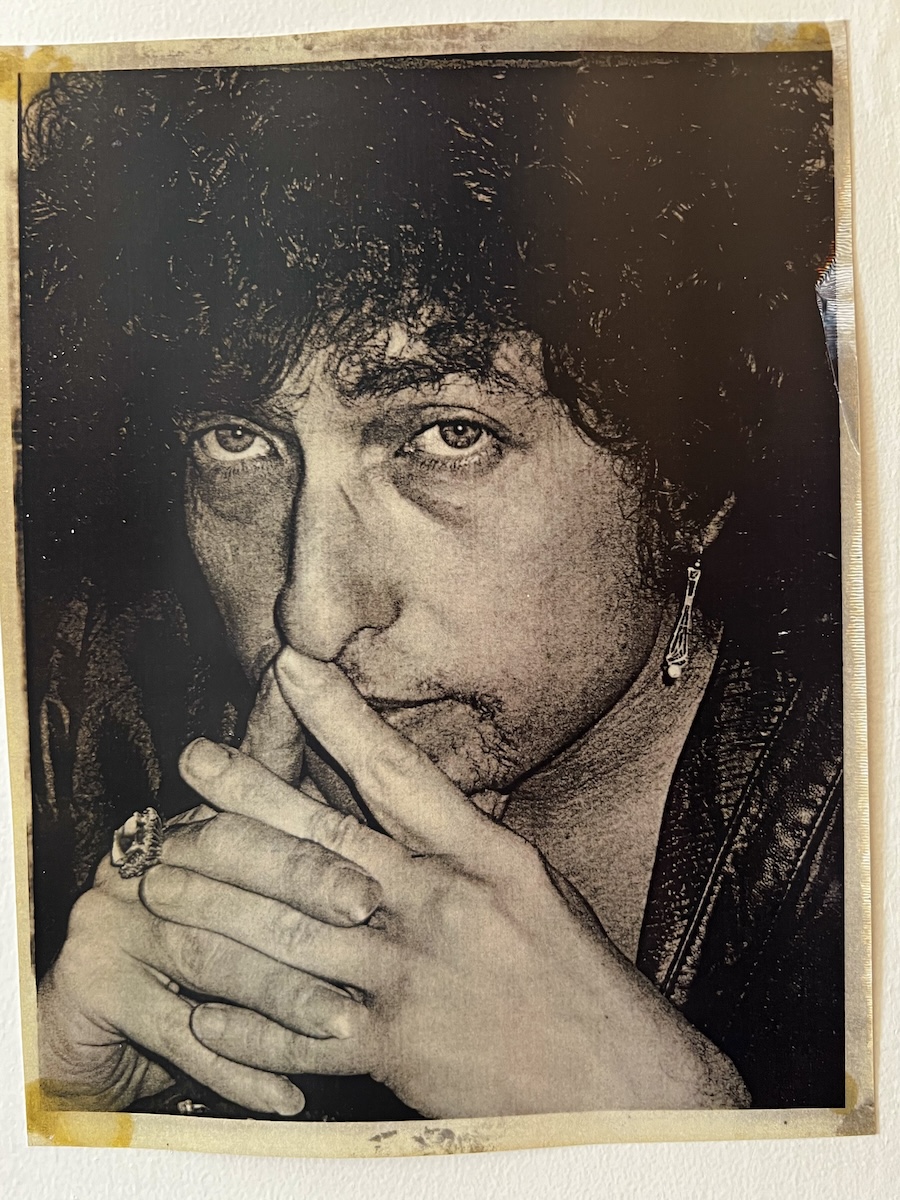

In 1967, he was awarded another scholarship, this time to study and work in New York. He and his young family lived in the Hotel Chelsea, where he met and hung out with artists and musicians like Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin. In the late ‘60s, New York was a playground for artists, activists, and anyone with a penchant for recreational pharmaceuticals. Never one to do things by halves, Whiteley threw himself into all three with gusto.

Alcohol, marijuana, and whatever else he could get his hands on became tools of the trade, portals to the subconscious that sometimes led to the emergency room rather than artistic enlightenment. He was twice admitted to the hospital for alcohol poisoning, proving that even genius has its limits—usually around the bottom of the bottle.

Early on, he was excited by the city, embarking on swirling, sensuous explorations of urban vitality and form. One of his early New York pieces, New York 1, painted in 1968, caught my eye at the studio. This canvas captures the frenetic 1960s energy of the Big Apple, with soaring buildings that twist and turn with real movement and a strategically placed nude female form obscured by a reflective silver starburst. I’m not sure I “got it,” but I loved it.

But Whiteley’s infatuation ended after about a year, and he woke up with a metaphorical hangover and a very real socio-political conscience. This was when he created his gargantuan The American Dream—which spanned 18 wooden panels and stretched nearly 75 feet in length. This piece was less of a painting and more of a fever dream committed to canvas. Starting with a serene ocean scene on the left, it steadily devolves into a chaos of explosions, flashing lights, and enough red paint to make a bull see, well, red. It was Whiteley’s technicolor scream against the Vietnam War, a psychedelic prophecy of impending doom that took a year of full-time work and, one suspects, several lifetimes’ worth of altered states to complete.

When his masterpiece was finally complete in 1969, Whiteley proudly presented it to his gallery, Marlborough-Gerson, expecting them to swoon. Instead, he was met with a resounding “Huh, yeah…nice. But no. Can we get more of that other stuff?”

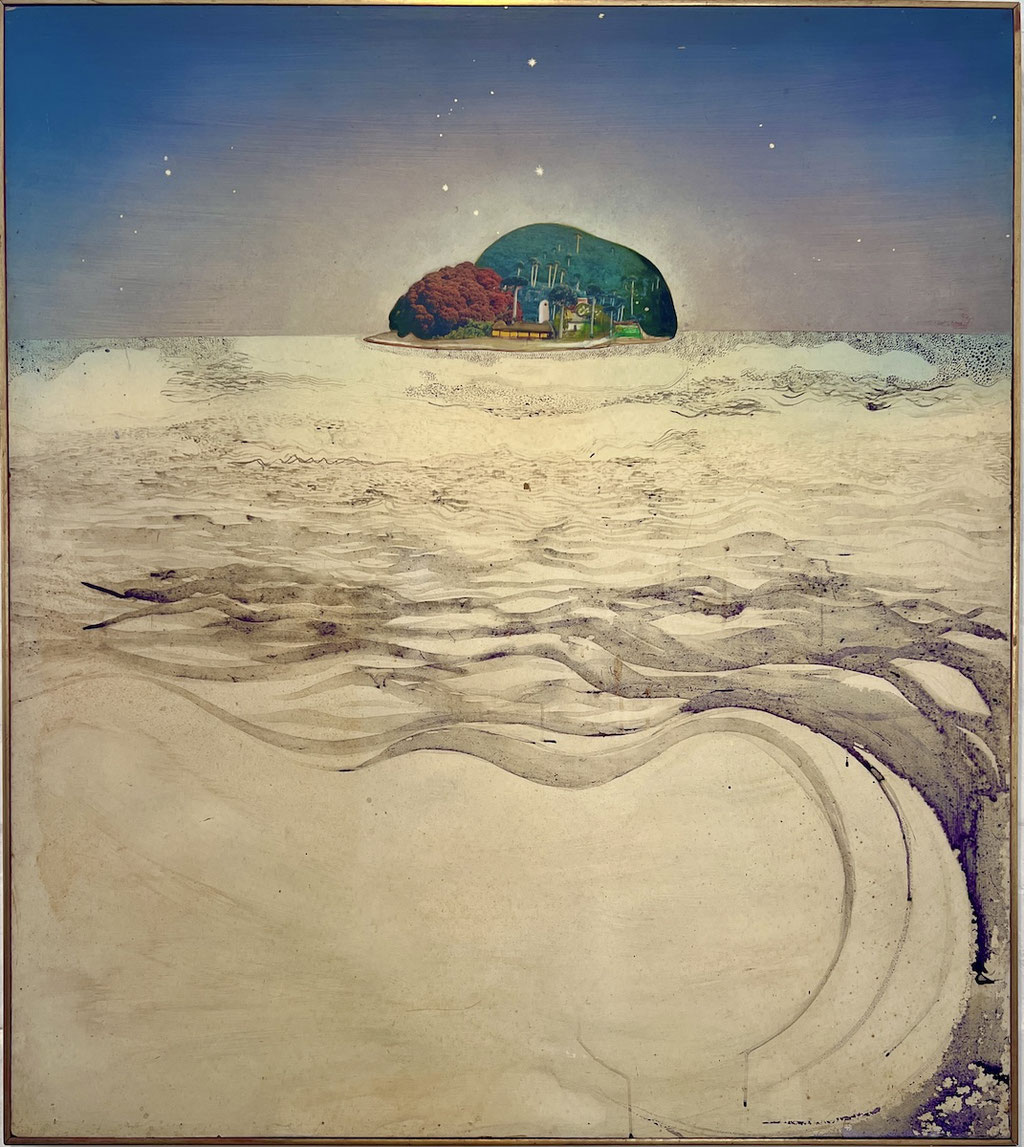

Devastated, Whiteley did what any self-respecting artist and young father would do—he bolted to Fiji. It was here that he had a bit of a creative epiphany—or maybe just a really good mai tai. Either way, Fiji infused his work with a new vibrancy and freedom. Whiteley’s art exploded with his tropical surroundings' vivid colors and lush forms. The studio has several paintings and artifacts from Whiteley’s time in Fiji, which he clearly loved. The family had found their slice of heaven.

Unfortunately, as it turned out, Fiji had a rather strict attitude towards recreational drug use. In about a year, the Whiteleys had to abruptly leave Fiji, allegedly due to Brett’s inability to leave his chemical muses behind. Given a choice between a hasty departure and an extended stay in less salubrious accommodations, the Whiteleys opted for the former and moved to Sydney.

Whiteley continued to work prolifically, his artistic vision forever altered by his Fijian stopover, but his personal demons, it seemed, had come back home with him. The 1980s saw him locked in a losing battle with alcohol and heroin, his brilliance increasingly overshadowed by his addictions. Critics may have cooled to his work, but the art market remained bullish on Brett. Despite numerous attempts to get clean, sobriety proved elusive. His marriage ended in 1989. He escaped into a new relationship, globetrotting and hobnobbing with rock royalty like Dire Straits.

In a final ironic flourish, Whiteley was made an Officer of the Order of Australia in June 1991. A year later, almost to the day, the enfant terrible of Australian art was found dead in a suburban motel room “due to self-administered substances.” A stark epitaph for a short life lived in vibrant, turbulent color.

Standing amid the treasure trove of artistic brilliance and beautiful chaos, it felt like the space captured the barely containable essence of the man and his art. I was struck by the enduring power of creativity—and maybe a little pang of sadness for the art that might have been, the masterpieces left unpainted. Whiteley may be gone, but his spirit lives on in every paint splatter, every scribbled note, every odd little object that caught his discerning eye.

Brett Whiteley’s Studio is, in my opinion, one of Sydney’s best-kept secrets.

The heroin clock, 1981

Write a comment