Walking into the Australian War Memorial, I was ready for a day filled with history and reflection. Little did I know, the War Memorial has two sections—the Hall of Memory, which I was there to see, and the War Museum, a labyrinthine mass of endless galleries devoted to all the wars Australia has been involved in since it became a country.1

And you have to go through the museum before you get to the Hall of Memory. Fine, I thought, I’ll learn some stuff on my way. So I wandered through the museum to see what was what.

I shouldn’t have. It's endless galleries of war memorabilia—uniforms, helmets, guns, letters, medals, and other paraphernalia painstakingly preserved and displayed for our viewing pleasure. The sheer volume of artifacts teetered between impressive and excessive. Was there a competition to collect the most obscure wartime relics? “Ah, yes, the famed sock of an Australian digger, worn during the battle of Mount-Someplace-Important. Riveting!”

More likely, we can't bring ourselves to discard anything that belonged to the young men and women who served. No matter how mundane, each item carries a piece of their story, a fragment of their sacrifice. The relics remind us of the humanity behind the history, the lives that were lived, but mostly those that were lost.

The Aircraft Hall was cool for a minute, with massive planes suspended from the ceiling as if they were about to dive-bomb unsuspecting museumgoers. The Hall of Valour, with its unending displays of servicemembers’ medals, was moving, but that wore off after about the third room.

Then you move into galleries devoted to individual wars, some of which I’d never heard of—the Boer War, the Boxer Rebellion, WWI, the Russian Civil War, the Armenian-Azerbaijani War, the Egyptian Revolution, the Malaita Punitive Expedition, WWII. After that, they start lumping them together as Conflicts 1945 to Today.

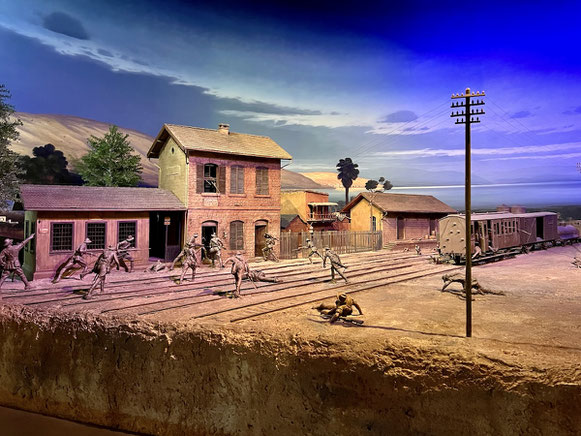

And the dioramas! Oh my gosh, the dioramas. These are not your average school project shoebox dioramas; these are intricate, sprawling scenes of historical carnage. They’ve recreated the Australian experience in WWI in giant models of key battles in which tiny soldiers are frozen in perpetual warfare. The world's most detailed and depressing dollhouses. “Come for the history, stay for the existential dread.”

Realizing this was not really what I'd come for—and after having gotten lost in the maze of misery more than once—I made a concerted effort to find my way to the shrine portion of the Memorial.

And that, that was beautiful. And, frankly, profound.

The Hall of Memory stands as the heart of the Australian War Memorial, a tribute to all who have fallen. The long walk past the Pool of Reflection and the Eternal Flame toward the Hall, beneath the names of more than 100,000 Australians who sacrificed their lives for their country, set a somber tone that was way less frenetic than inside the museum.

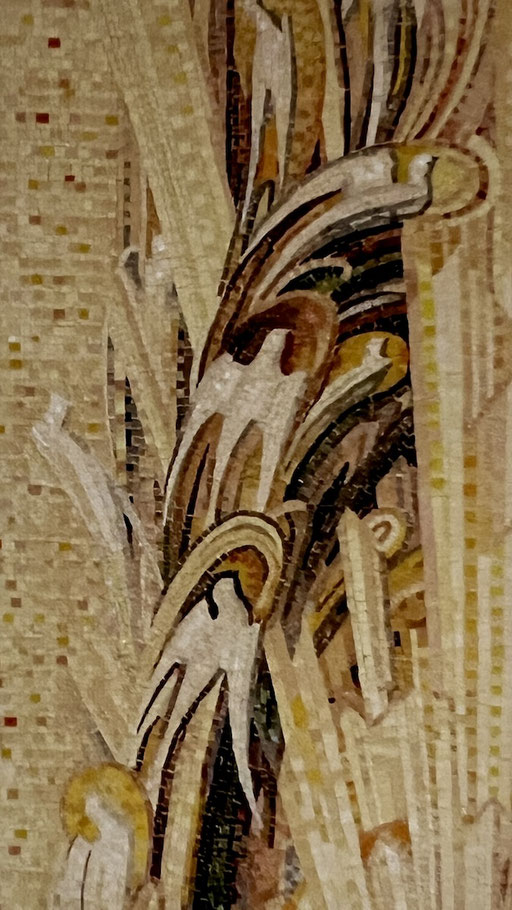

Inside, the Hall of Memory is dominated by the massive Byzantine-style dome that looms over the Tomb of the Unknown Australian Soldier. The golden mosaic depicts souls ascending to heaven. The dome is surrounded by a wreath of Australian wattle and a flock of black swans.

I could stare at the dome for hours if I didn’t get a crick in my neck so bad. It’s mesmerizing.

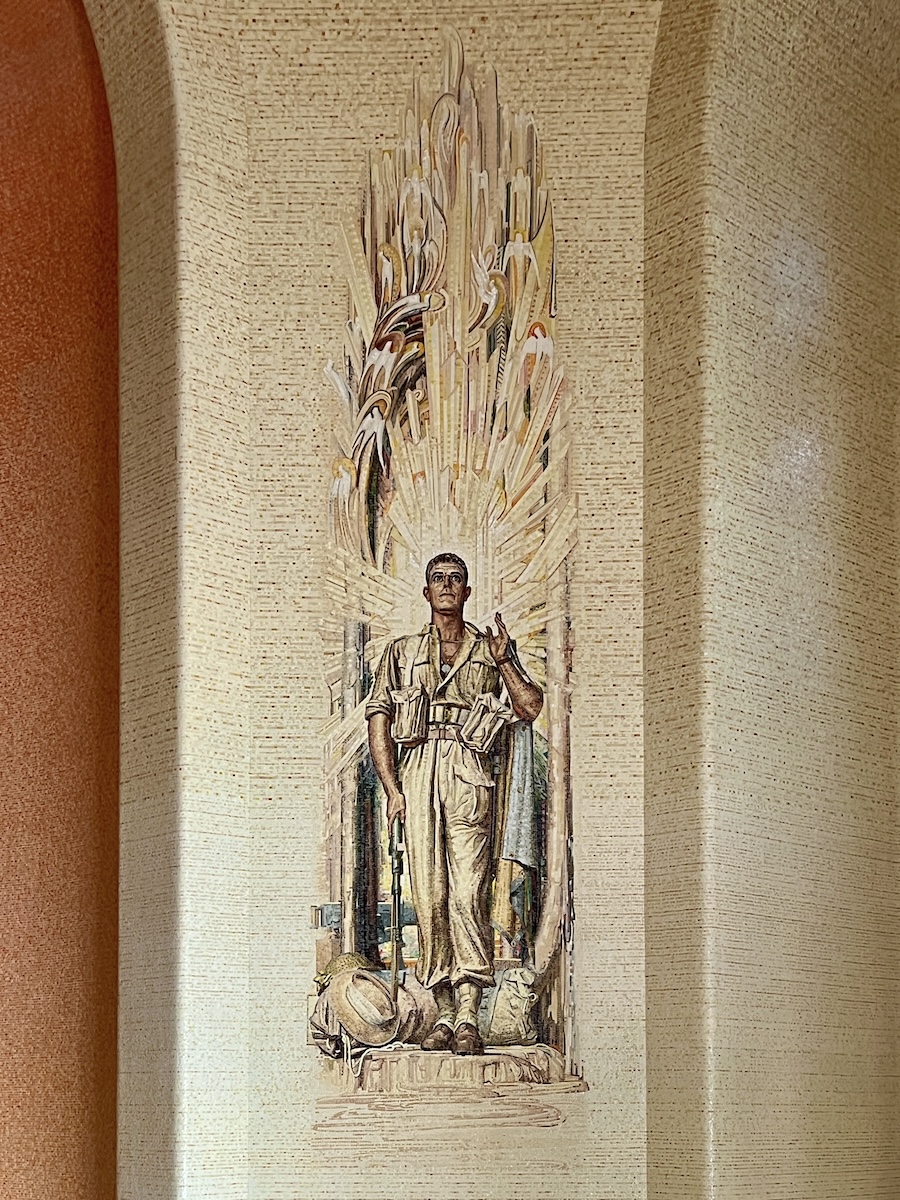

When you finally tear yourself away from the dome, you see the wall mosaics facing inward. Dedicated to WWII, each figure—representing different branches of service, Navy, Army, Air Force, and Women's Services—stands with a formal posture and large eyes, symbolizing vigilance and sacrifice. The centaur over the servicewoman represents the hospital ship Centaur, which was sunk by a Japanese torpedo, killing all but one of the nurses on board. My favorite is the gargoyle above the airman, though I never figured out what it represented.

Between the mosaic figures are gorgeous stained-glass windows, each divided into five panels depicting WWI figures. Each figure represents "quintessential Australian qualities” such as resourcefulness, devotion, curiosity, and loyalty—my favorite was coolness. The colors and designs combine blue and grey to evoke serenity and a dim cathedral light.

The mosaics, dome, and stained-glass windows were all designed and produced by one man—Napier Waller. Waller dropped out of school to work the family farm when he was 14. At 20, he moved to Melbourne to study art and then enlisted in 1915. He lost his right arm in 1917 at Bullecourt, so he had to learn how to write, draw, and paint all over again with his left hand. He was selected to create the Hall’s decorative elements in 1937, beginning with the stained glass. The windows were installed between 1947 and 1950, and the mosaics were installed between 1955 to 1958. More than six million tiles (or tesserae) were used for the figures and the dome.

The Tomb of the Unknown Australian Soldier, at the center of it all, holds the remains of "An unknown Australian soldier killed in the war of 1914–1918" brought back from France in 1993. Flanking the tomb are the Four Pillars, each representing one of the elements—Air, Fire, Earth, and Water.

Designed by artist Janet Laurence and architect Peter Tonkin, the pillars are over 30 feet tall. Air is made of polished jarrah wood, Fire is made of steel, Earth is carved from marble, and Water pillar is made of glass. They are monumental and a fantastic, modern counterbalance to the Art Deco design of the rest of the Hall.

Just outside the solemn Hall of Memory is a sculpture garden dotted with figures and memorials that invite further reflection. I mostly went out there to see the newest addition, For Every Drop Shed in Anguish by Alex Seton—a series of rounded liquid forms carved from marble to suggest blood, sweat, or tears. War by Bertram Mackennal stands nearby, a classical bronze sculpture that powerfully captures the grim reality of conflict.

For Our Country by Daniel Boyd also captivates. A circular wall of mirrored glass invites visitors to see themselves as part of the story, and a central pool gives a nod to the contributions of Indigenous Australians to the nation’s military history.

My favorite part, though not technically a sculpture, was an Aleppo pine tree planted in 1934. The tree grew from a pinecone an Australian soldier picked up at Lone Pine on Gallipoli, where his brother had died in 1915. He found the cone on branches used by the Turks to cover their trenches and sent it home to his mother. She, in turn, offered it to the Memorial in honor of her son and everyone else who fell at Lone Pine.

That puts a lump in your throat.

In the end, despite being a bit put off by the museum itself, the Australian War Memorial was everything I’d hoped it would be. The blending of classic and modern elements felt both timeless and innovative. The meticulous mosaics, the grand Byzantine dome, and the serene Sculpture Garden all come together to create a space that is as stunning as it is respectful. The Memorial is not just a place of reflection but a genuine feast for the eyes.

Write a comment