For 50 years, Australia's political drama played out in the Old Parliament House in Canberra1. And, boy, are there stories to tell, though they might bore you to tears if you’re not careful. Because, you know…politics…Australia…Canberra. You get it. But we went to see it anyway.

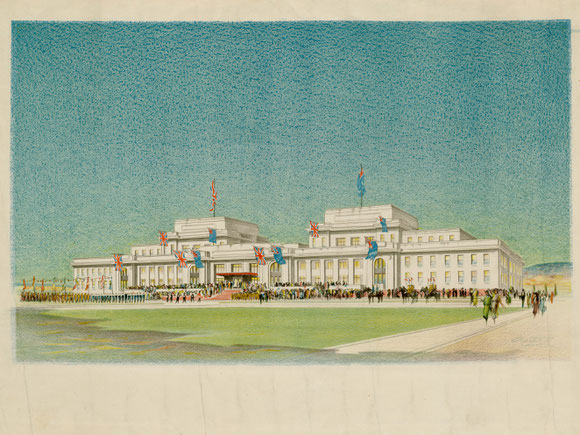

The building is what they call “simplified” neoclassical, meaning it's the stripped-down, budget-friendly version. It’s like someone thought, "The Parthenon, yeah. Greek, inventors of democracy, grand, staying power—that's what we need! But what if we did it without all the fancy bits?"

The result was a building that stands a stately three stories tall, managing to be both underwhelming and merely functional, much like a bureaucrat in a cheap suit.

A little history is what we need here.

Old Parliament House—though back then, when they still only had zero parliament houses, they called it Provisional Parliament House—was basically forced on the nation after many, many years of bureaucratic dithering. Australia became a country in 1901 at Federation when all six colonies elected to join together as a single nation. A nation without a capital, mind you.2 Or a parliament house.

So the brand-spanking-new and freshly elected Australian Parliament looked around and decided the Victorian Parliament House looked pretty sweet. It was built in 1856 when Victoria had money to burn, so it was, in fact, a pretty great building. Without ado, the feds kicked the Victorians out of their own house and moved on in.

While they were having house parties and generally running the place down, the Victorians had to make do meeting in a drafty, leaky old exhibition hall up the road. After about 14 years and with no end in sight, the Victorians began making noises about how the feds really needed to move to the capital, Canberra, and vacate their beautiful home at the end of Bourke Street.

The only course of action the Federal Parliament could take, of course, was to appoint a committee and launch an ambitious international design competition for a permanent Federal Parliament House.3 Unfortunately, being 1914 and all, WWI rudely interrupted their grand plan, diverting attention and funds elsewhere.

In 1923, after various attempts to revive the international design competition had failed, the government finally threw in the towel. They indefinitely suspended the competition—the war left the country with a hefty war debt, and constructing a monumental building was about as high on the priority list as a cup of tea in the middle of a bushfire.

Instead, they turned their attention to something more immediate and achievable—a "provisional" Parliament House. This was the architectural equivalent of a temporary shed meant to last a few years but ended up sticking around for longer than six decades.4 The decision was driven by practicality and a dire need to escape the increasingly passive-aggressive grumblings of the Victorians in Melbourne. It just wasn’t fun anymore, I guess.

The architect chosen for this task, John Smith Murdoch, embraced the challenge with the enthusiasm of someone told to build a palace out of plywood and plasterboard. His design philosophy was simple—keep it functional, keep it cheap, and, for the love of all things parliamentary, make it quick.

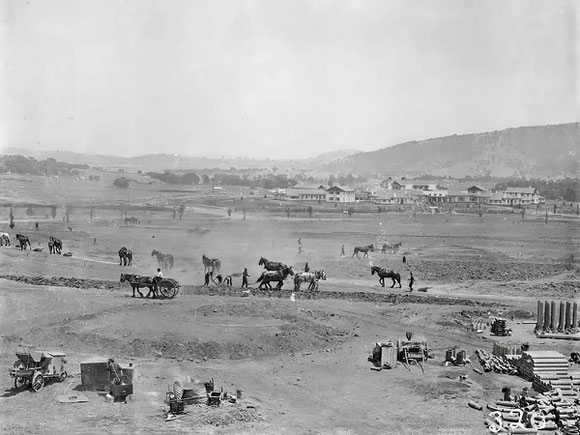

It still took four years to build it but build it they did. Workers toiled with local Canberra clay bricks, timber, and cement. The result was as utilitarian as it was boring. The roof is just slabs of concrete, a metaphor that characterized the entire project if there ever was one. It was completed in 1927, and the feds decamped Melbourne for Canberra with a sniff and a snooty "bye, Felicia" from the Victorians.

And there it stands today—testament to the nation's pragmatism and proving that sometimes, the best-laid plans are the ones you slap together when you have no other choice. Of course, it’s not Actual Parliament House5 anymore, it’s a museum.

Stepping into the Old Parliament, you’re greeted by a bronze statue of good ol’ King George V in a large, square King’s Hall built from silver ash wood and jarrah. It's impressive if you squint a little and imagine it’s grander than it actually is. George earned this honor by accidentally being in charge of the empire when they built the building. He stands there, looking regal and slightly bemused, probably wondering why he got stuck in a governmental stopgap measure instead of the full meal deal up the hill. It’s all about timing, I guess.

King’s hall serves as a central foyer and a grand entrance to the building, with the House of Representatives and the Senate chambers located on either side. This layout was designed to facilitate easy access between the two chambers and to highlight the hall’s significance as a central gathering and ceremonial space within the building. It also emphasizes the bicameral nature of the Australian Parliament, with both houses linked physically and symbolically.

Wandering the (former) corridors of power, you're struck by nostalgia and mild irritation. The building is a labyrinth of rooms, each more unremarkable than the last, yet imbued with the gravity of historical decisions. Like your grandmother's house, everything is outdated, but you can’t help but feel a strange sense of respect for the lived-in wear and tear.

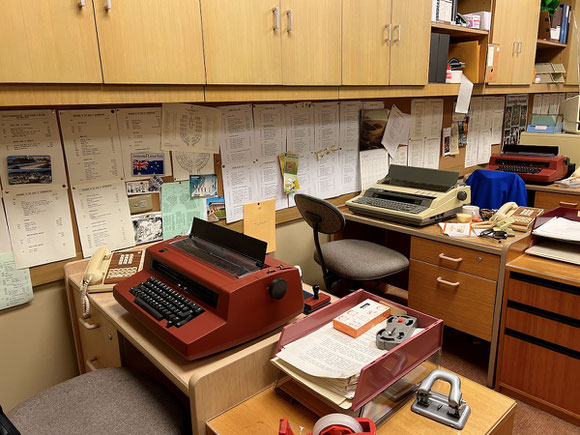

The place was filled with numerous rooms for the rank-and-file members of Parliament. Which makes sense. Part of the reason they were so keen to build the Actual Parliament was because this building became increasingly cramped with each passing year. Each member had a modestly sized office, but some had to share. And I’m not kidding when I tell you that it looked like some of those offices were minimally transformed storage rooms and supply closets. All of them were furnished with the bare essentials—a desk, a few chairs, and a filing cabinet that probably hadn’t seen the light of day since the 1950s. The décor, a mix of functional drab and accidental kitsch, lent an air of determined mediocrity.

Grander and more comfortable were the Government Party Room and the Senate Opposition Party Room. The Government Party Room was used as a meeting room for the governing party. It was the site for robust party meetings, heated political debates, and more than a few leadership challenges. Routine and quieter parliamentary business also took place there, with MPs dropping in to consult reference books, collect their mail, read newspapers, and make telephone calls.

The Senate Opposition Party Room was ostensibly a sanctuary of quiet contemplation and legislative study for Senators of parties other than the governing party. In practice, though, it was where they could retreat from the frenetic pace of political life to read a newspaper, flip through hefty government reports, or enjoy film nights. The room was lined with bookshelves holding an eclectic mix of legal tomes, parliamentary records, and policy documents. It featured comfortable club-style lounges, easy chairs, mailboxes, and soundproof telephone booths.

Old Parliament House was also home to government administrative offices. The last administration to have offices here was Bob Hawke’s, who served as Prime Minister from 1983 to 1991. It was his administration that moved to the new Parliament House in 1988.

Which means that walking through the government offices at Old Parliament is like stepping onto the set of a period political drama—one set in the big-hair era of the 80s—complete with wood-paneled walls and plush carpet that probably witnessed more backroom deals than an underworld poker game.

The Prime Minister’s office, a well-appointed but clearly a working room, was a space of significant decision-making. The Speaker of the House’s office, though more modest, came outfitted with a formal dining room, a testament to the importance of hospitality in political affairs. The Cabinet Room, emanating quiet power, was small, reflecting the size of Australia but not its influence. The boardroom-style table surrounded by low-backed leather chairs looked like something out of a movie, a setting for high-level discussions and strategic planning.

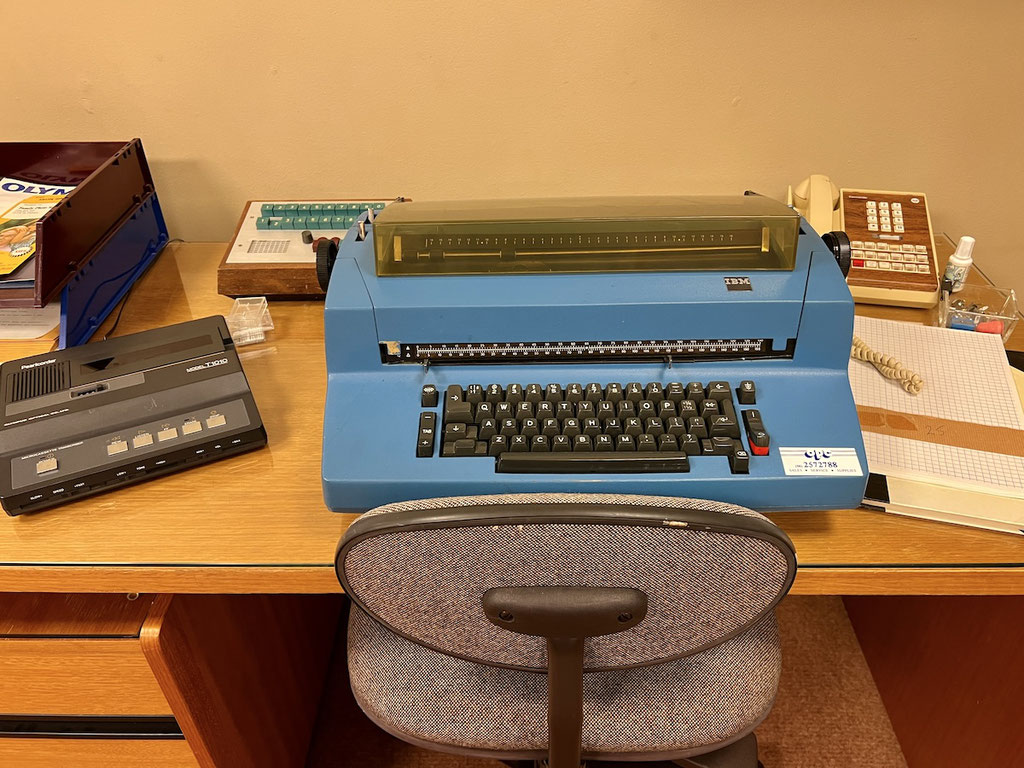

Staff offices looked like everyone had just left for the day—a hive of frenetic activity frozen in time. IBM Selectrics, once the cutting edge of administrative efficiency, sat silently, their keys covered in a fine layer of dust. Filing cabinets filled with yellowing documents and manila folders lined the walls like sentinels of forgotten paperwork. And everywhere you looked, there were reminders of the 80s—the beige computers with their floppy disks, the pastel-hued office supplies, and the posters extolling the virtues of productivity and teamwork in the most uninspired fonts imaginable.

Strolling through these offices, one couldn't help but feel a sense of nostalgia for a simpler, if somewhat gaudier, time. It was a living museum of Australia’s political past, a place where the decor might have been dated, but the spirit of governance and debate remained timeless.

In hindsight, the Old Parliament House was a fitting stage for the young nation's political theatre. It’s unpretentious, straightforward, and a little improvisational—kind of like Australia itself. The building may not boast the grandeur of its European counterparts, but it’s a testament to Australian ingenuity and resilience, cobbled together in a typically no-nonsense fashion.

Today, as a museum of Australian democracy, the Old Parliament House reminds us that while we might aspire to marble columns and sweeping arches, sometimes all you need is a bit of brick and mortar to get the job done. And maybe a bronze king watching over you, silently judging the entire spectacle.

Write a comment