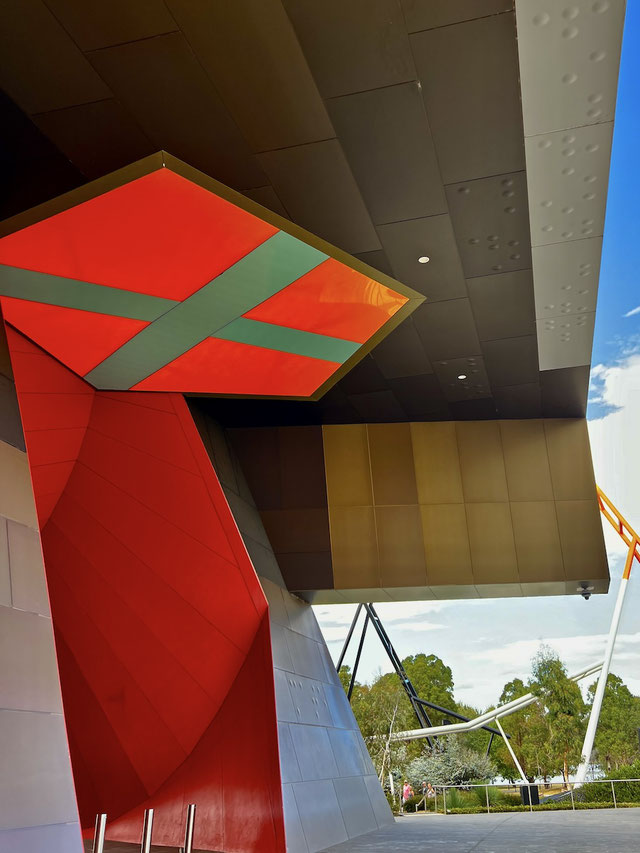

At the end of Canberra’s Acton Peninsula, jutting out into Lake Burley Griffin, is a perplexing building that just doesn't seem to belong with the rest of Australia's capital city—which is predominantly mid-century modern concrete and glass. This museum is a bold, postmodern design that captures the imagination.

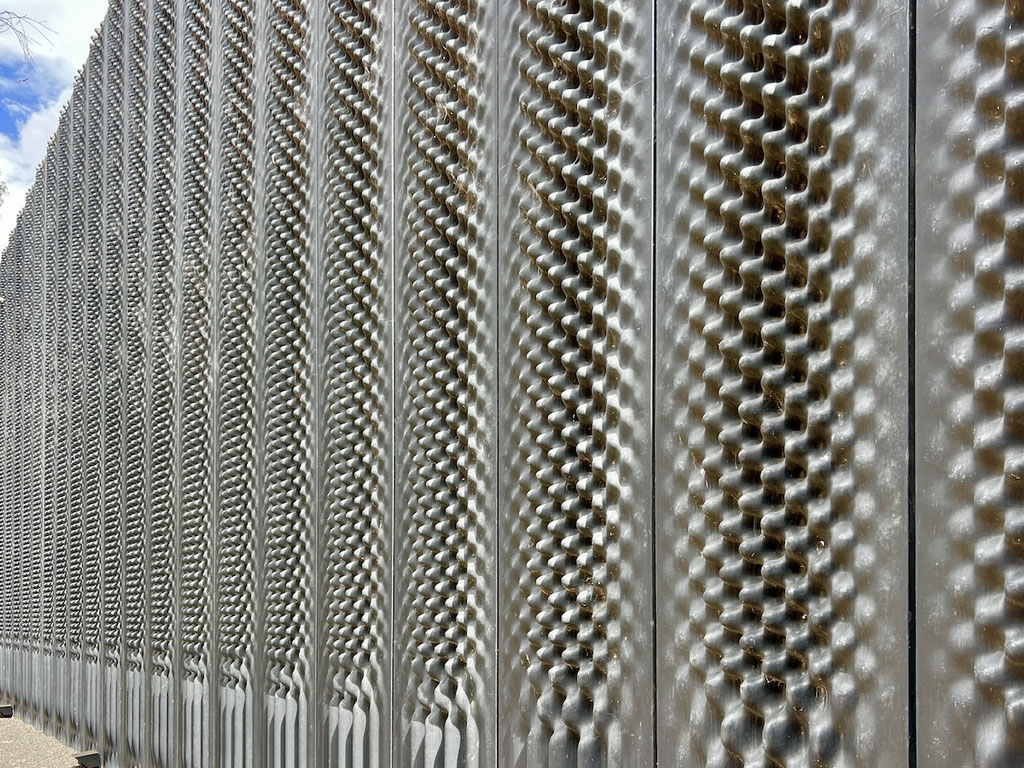

The museum’s exterior is a riot of colors—crimson, orange, bronze, gold, black, and brushed silver—creating a dynamic visual feast. The textures are equally varied, from the smooth finish of anodized aluminum panels to the deeply patterned concrete walls with colossal inscriptions in braille.1

The National Museum of Australia replaced the Royal Canberra Hospital on the Acton Peninsula.

Courtesy of National Archives of Australia

The approach to the museum is marked by a series of unexpected architectural elements. A native garden introduces a touch of Australia’s wild beauty, contrasting with the modernity of the museum. The curving Loop, symbolizing a journey through Australia’s history, draws visitors toward the main entrance in a seamless flow. The Welcome Wall delights with its reflective surface etched with thousands of names that tell stories of migration and heritage. These elements combine to create a unique and thought-provoking entry experience that hints at the innovative design within.

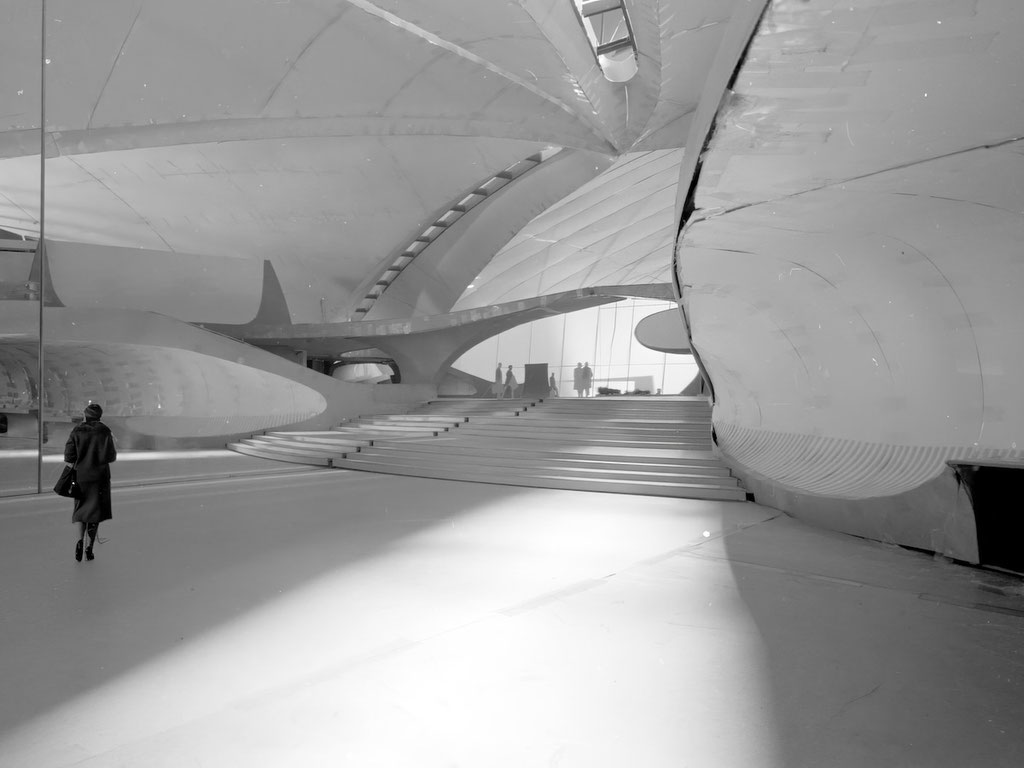

Inside, the soaring atrium is a gigantic, light-filled knot that is a nod to Eero Saarinen's iconic TWA Terminal at JFK. The Main Hall echoes the same sense of movement and dynamism with fluid lines and towering windows overlooking the lake. This area is not just a central meeting spot, it’s also a gallery that features some of the museum’s most impressive large objects.

The museum's Main Hall design was inspired by the TWA Terminal at JFK in the 1960s.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Here is where you find a 1955 FJ Holden Special in near-mint condition and a vintage caravan that symbolizes the quintessential Australian family road trip and spirit of adventure.2 A cool neon art piece hovers delicately above everything, Reko Rennie’s Bogong Moth.3 You’ll also find the massive skeleton of a Muttaburrasaurus.4

The museum exhibition spaces cleverly integrate gallery space and building design. The architecture informs the exhibition layouts, with elevated platforms providing impressive views over three levels. Rich, warm colors and natural materials create intimate and energetic spaces, making the stories come alive. Feature windows capture stunning vistas of Canberra and the surrounding landscape, blending indoors and out. Whether having a nosh and a cocktail at a cafe overlooking the lake or exploring the museum's amphitheater, the museum offers a visually exciting experience.

At the heart of the museum lies the Garden of Australian Dreams, an outdoor courtyard that’s an exhibition piece itself. This outdoor space is a symbolic landscape representing a slice of central Australia. The Garden's contoured concrete surface features complex maps intertwining histories and cultures, offering a space for reflection and exploration. The maps display the word for “home” in the hundred or so languages spoken in today’s Australia. 5 These words are overlaid with names of various Aboriginal mobs6 and languages, inscriptions that honor the traditional custodians of the land and celebrate the linguistic diversity of Indigenous Australia.

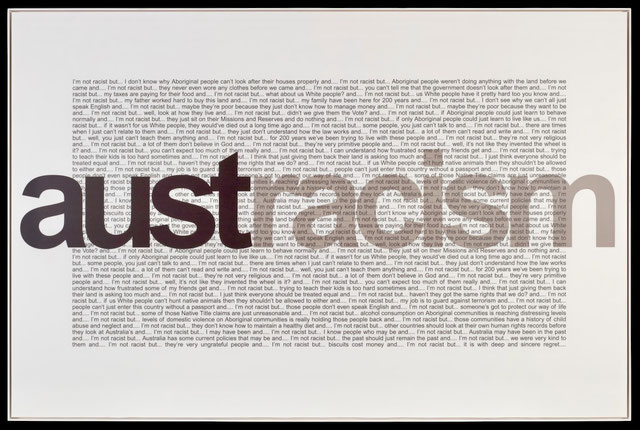

Through the Garden lies the First Australians gallery, which is devoted entirely to the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Works old and new are displayed over two floors and include a powerful Talking Blak to History exhibition, which speaks to colonization and explores issues including land rights, sovereignty, the Stolen Generations, and deaths in custody.7 The First Australians gallery, with its zigzag form, is a “tribute” to the Jewish Museum in Berlin,8 symbolizing the struggles and triumphs of Indigenous Australians.

Austracism, 2003 (Vernon Ah Kee)

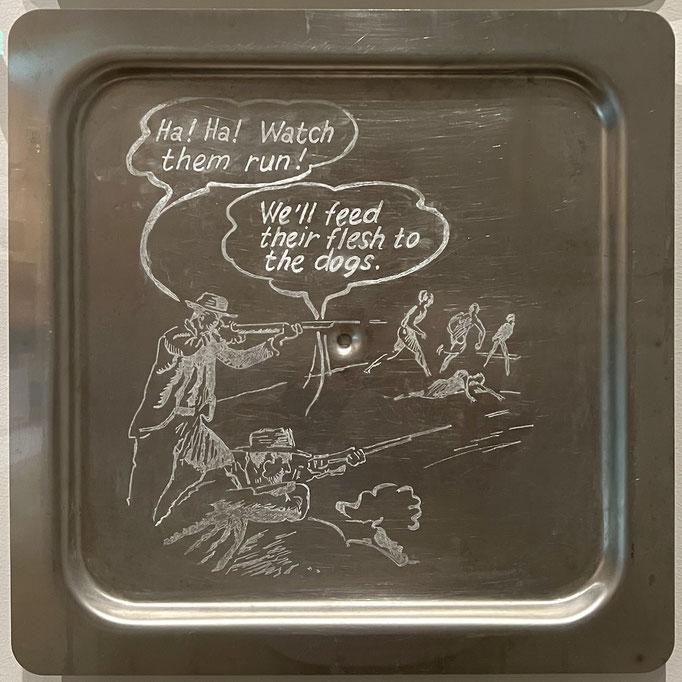

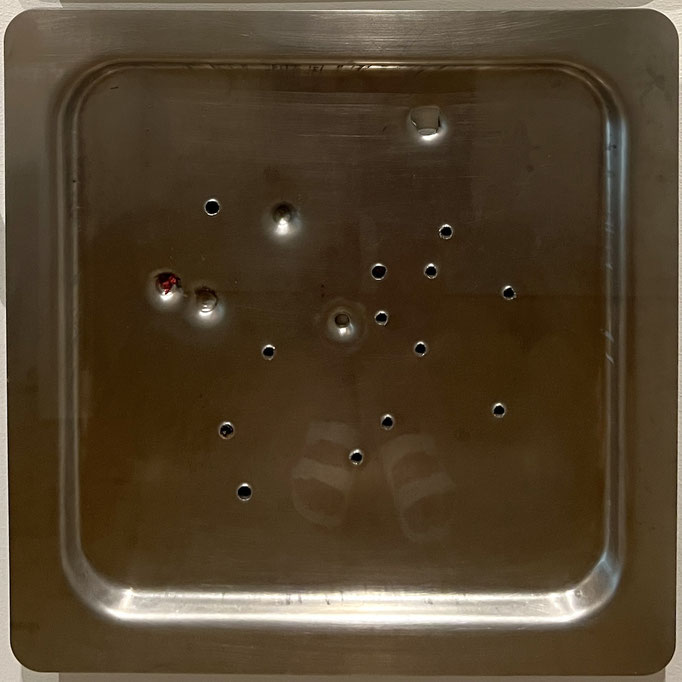

Hunting Party (Barbeque Area), 2014 (Julie Gough)

Leaving the Museum and learning what you've learned, the Uluru line becomes more apparent—and comprehensible. The Uluru line is a relatively significant sculptural feature that joins with the Loop that was so obvious at the entrance. It begins at the entrance to the museum and continues as a bright red footpath to the east. You can now grok the 30-meter-high Loop as a modern interpretation of the rainbow serpent that figures prominently in Aboriginal Dreaming stories. From the Loop, the red Uluru line symbolically extends all the way to Uluru—the massive sandstone monolith at the heart of Australia that holds profound spiritual significance for Australian Aboriginal peoples—connecting the museum to the broader Australian experience.

Honestly, even if you’re not into the historical exhibits at the National Museum of Australia, you’ve got to be impressed by its bold architectural statements.

Write a comment