Fremantle Prison looms over the hipster paradise of Fremantle1 like a stern headmaster. Built between 1852 and 1859, this massive limestone fortress is something of a local celebrity, chiefly because it's impossible to ignore a hulking structure with "Don't mess with me" written all over it. It's not every day you see a building that's both a dire warning and a tourist attraction.

Originally, the Swan River Colony (now Perth and its suburbs, including Fremantle) was a "free colony," meaning they did not intend to ship in British convicts when it was founded in 1829. But the early settlers, mostly landed gentry from northern U.K., were much more gifted with optimism than skills. Or supplies. Or sense. They were wholly unequipped to deal with the harsh environment, so 20 years in, they still didn't even have a town or functioning government. And their population was dwindling.

With disaster imminent, the colonists wrote to the Crown begging for convicts. They put the letter on a ship back to London and bided their time. The King had been sold on allowing the colony in the first place because, as a free colony, colonists would pay their own way to get there. So, the Empire would gain more territory without any significant cash outlays.

But the Industrial Revolution had turned society upside down, and there was a spike in crime—because, apparently, not everyone was thrilled with working 16-hour days. The King was amenable to the idea, so he drafted a fancy letter accepting the colonists' request and sent it off on the first ship leaving. He sent the convicts on the second ship leaving.

Unfortunately, global travel at the time being what it was,2 the ship with the convicts arrived first! Needless to say, the colonists were a bit taken aback. There they were, standing on the shore, facing 75 convicted felons and nowhere to put them. Yikes!

The colony did have a tiny, baby little prison—the Round House3. But it only had eight cells and a jailer’s room. So the convicts were housed, well, everywhere—in a wool shed and nearby warehouses, in rudimentary lean-tos they slapped together, and even in tents. But no worry. The colony suddenly had laborers! In a cruelly ironic twist, the first job on the convicts’ to-do list was to build their own prison.5

Nice.

Anyway, I had to visit the place. Twice. I mean, Rick really only had it in him to do it once, but there was SO MUCH MORE to see. So I tricked persuaded our friend Mali to go back with me

a second time. This is an amalgam of both visits. So it’s twice as long as usual. Lucky you!

Imagine a place designed not for comfort but for maximum security and minimum morale. Then add a gift shop and, voilà, you've got yourself a major tourist attraction! This prison, Colonial Alcatraz, has been out of the penal business just long enough to become quaint,6 which means it's perfectly acceptable to stroll through and comment on how dismal life must have been while sipping a latte from the café by the front gate.

Our chirpy guide—let’s call him Kevin—led us through the menacing front gates rusty from decades of regret and tears with so, so many jokes about us being prisoners and watching our step or we’ll never get out blah blah blah. Har har. Honestly, Kevin’s irrepressible cheeriness in such somber surroundings suggested he’d misunderstood his assignment.

After establishing the ground rules of visiting a high-security prison, albeit a defunct one, we ventured into the heart of despair—the kitchens. This is where some of the luckiest prisoners worked seven days a week. The jobs offered a break from the monotony of cell life and allowed them to learn a trade for when they were released. More importantly, it offered a break room and a small exercise yard separate from the general population. Sweet! The exclusive VIP section of a club nobody ever wanted to join.

Moving on, we went out to the larger recreational yard for the not-so-special non-kitchen workers. This is where inmates presumably exercised their right to walk in circles and ponder the existential dread of their situation. For the first few decades of the prison, convicts had to work—building the prison itself, the Perth Town Hall, roads, bridges, jetties, and any other infrastructure the colony needed.

That went until, oh, say, 1885. After that, prisoners weren't sent out to work anymore. So they mainly were sent out into the rec yards for most of the day every day. Regardless of the weather. And the shelters you see weren't added until the late 1970s or 1980s. In cold weather, the jailers might put out urns of hot water so prisoners could make themselves hot drinks—but they ended up using the water to scald each other in fights instead.

The tour continued inside with what I can only describe as a peppy lament over the harsh realities of 19th-century prison life. Each cell was a masterpiece in the art of squeezing human misery into a space no larger than a pantry, outfitted in Early Australian Despair with original scratched graffiti that read like the world's saddest guest book. Some inmates—Aboriginals or those with little left in their sentence—were given supplies and allowed to paint their walls.

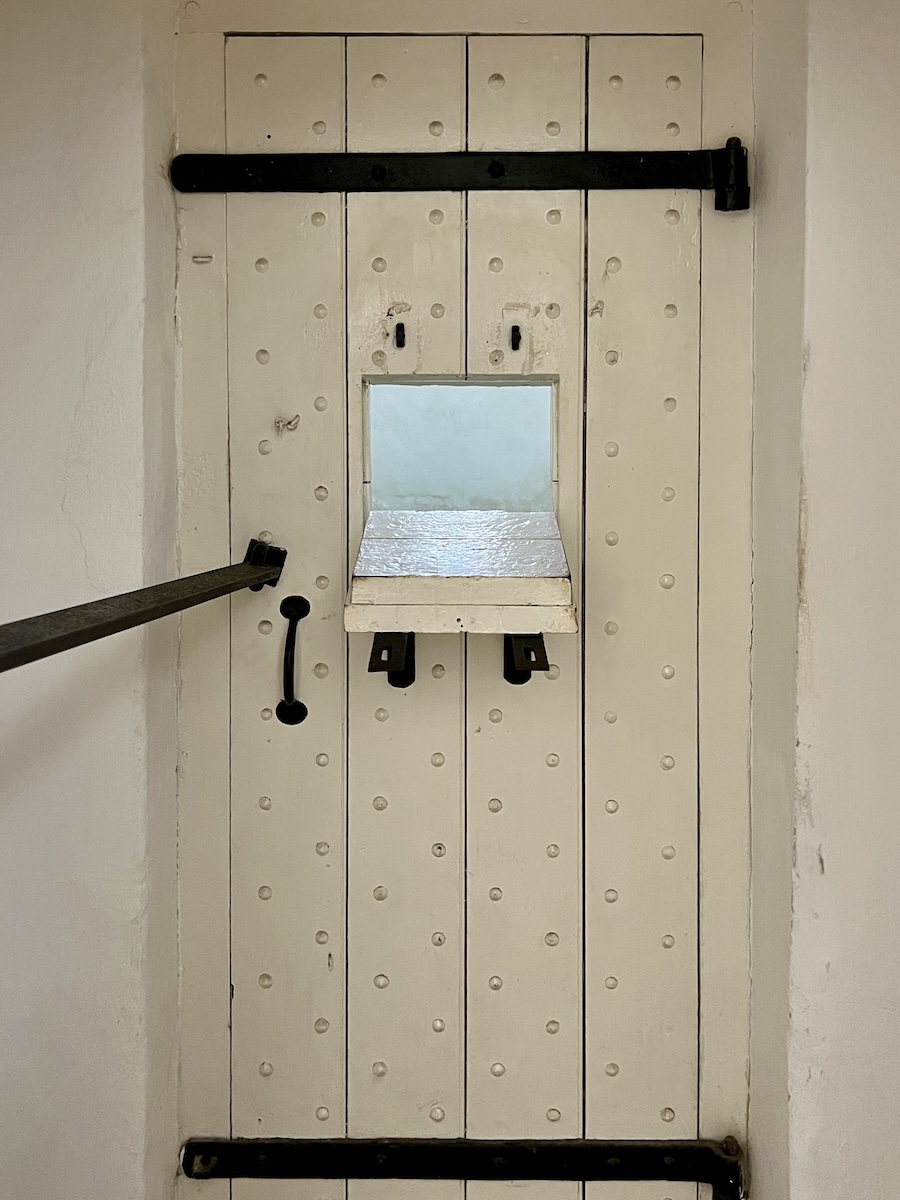

There were plenty of solitary confinement cells—12 punishment cells and six lightless cells called "the silence rooms"—each built as double chambers with inner and outer doors for added security. In the punishment cells, prisoners had their toilet bucket, a bed without a mattress, a blanket, and a bible. In the silence rooms, prisoners had, well, silence. These prisoners often became disoriented and lost track of time. Stays in solitary were between one and six months. “Some inmates spent weeks here!” Kevin exclaimed, suggesting this was a personal accomplishment instead of an achievement in survival.

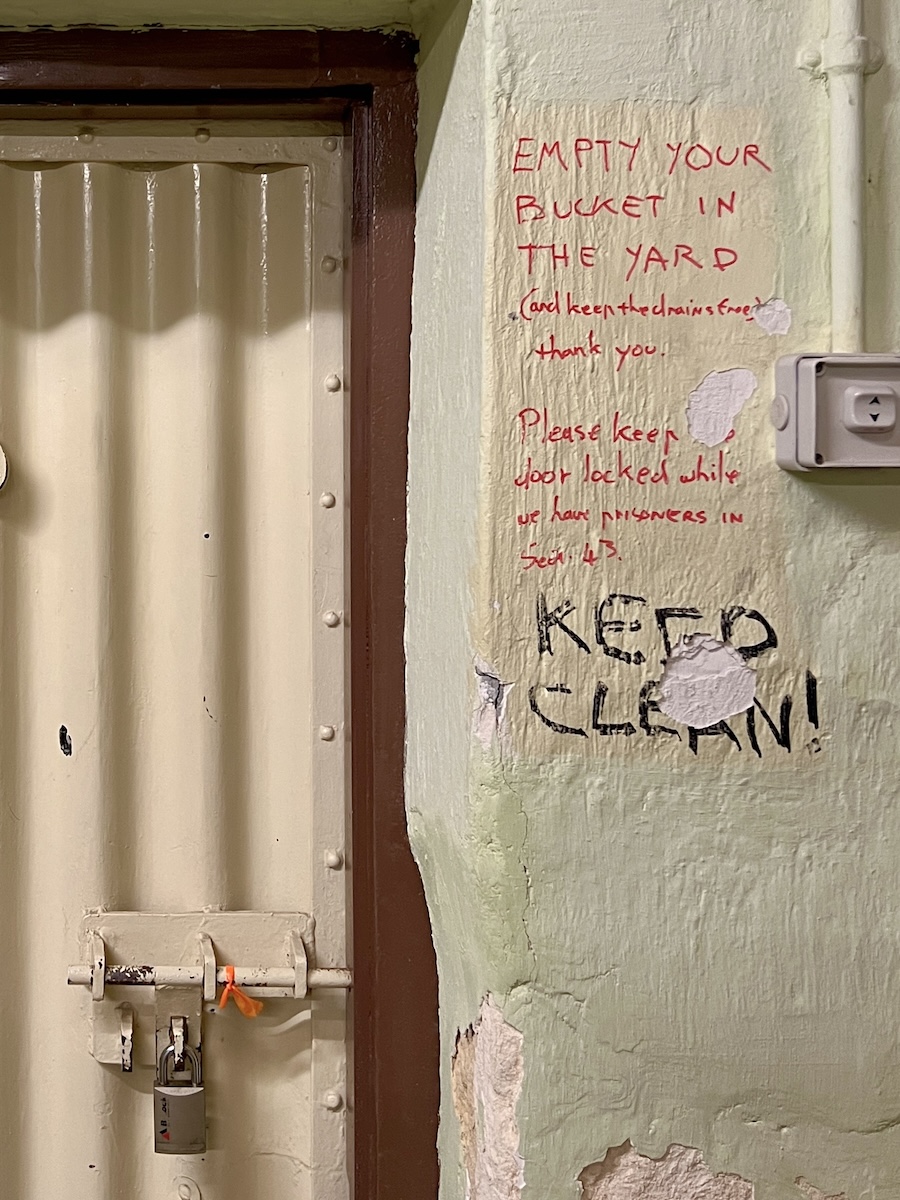

Speaking of toilet buckets…Fremantle Prison never had running water in any of the cells. Prisoners had to use the infamous red toilet buckets. There were two per cell, one for waste and the other for fresh water. And cellmates had to share. The buckets they were using when the prison shut down in 1991 were the same buckets the prison started with in 1859.

At one point, they introduced composting toilets, but prisoners tried to drink the alcoholic solution in the toilets. The fancy new toilets were promptly un-introduced, and the prison returned to the bucket system. Gross.

We saw the Hanging Room. Between 1888 and 1984, this was the only legal place of execution in Western Australia—though the last person to be hanged here was a serial killer in 1964. In all those years, they hung just one woman. Martha Rendell was accused of murdering her diphtheria-stricken stepchildren by swabbing their throats with hydrochloric acid. In fact, pharmacists at the time prescribed just that for diphtheria.

But Martha lived with the children’s father while he was separated from his wife, and public opinion, fueled by sensationalist media and lurid tales of a wicked stepmother, swung against her. Martha maintained her innocence to the bitter end. Even her prison guards were moved to tears at her execution. It’s possible she was executed for not being sympathetic. Dickensian.

Better stories were the escape stories. Escapes were like “prison Olympics," with inmates competing to be the craftiest. Moondyne Joe, Houdini of the bushland, was the Michael Phelps of prison escapees. He was in and out of prison and had escaped a couple different times. The governor ordered a special escape-proof cell lined with ultra-dense jarrah sleepers secured with extra-long nails. He even sarcastically promised to pardon Joe if he got out again. You know where this is going, right?

Joe was put to breaking rocks under strict supervision. After many days, he’d created quite a large pile of rubble conveniently near the prison wall. Now, partially hidden behind the pile, Joe dug a hole through the prison wall with his pickaxe and disappeared into nearby bushland.

Hahahaha! I love it.

And then there was John Boyle O’Reilly, who had arrived with 62 Fenians, Irish nationalists who had been arrested and sent to Fremantle by the British. O’Reilly befriended a local Catholic priest who helped him escape aboard an American whaling vessel in 1869. O’Reilly made it to Boston, where he settled and eventually became editor of the Boston Pilot newspaper.

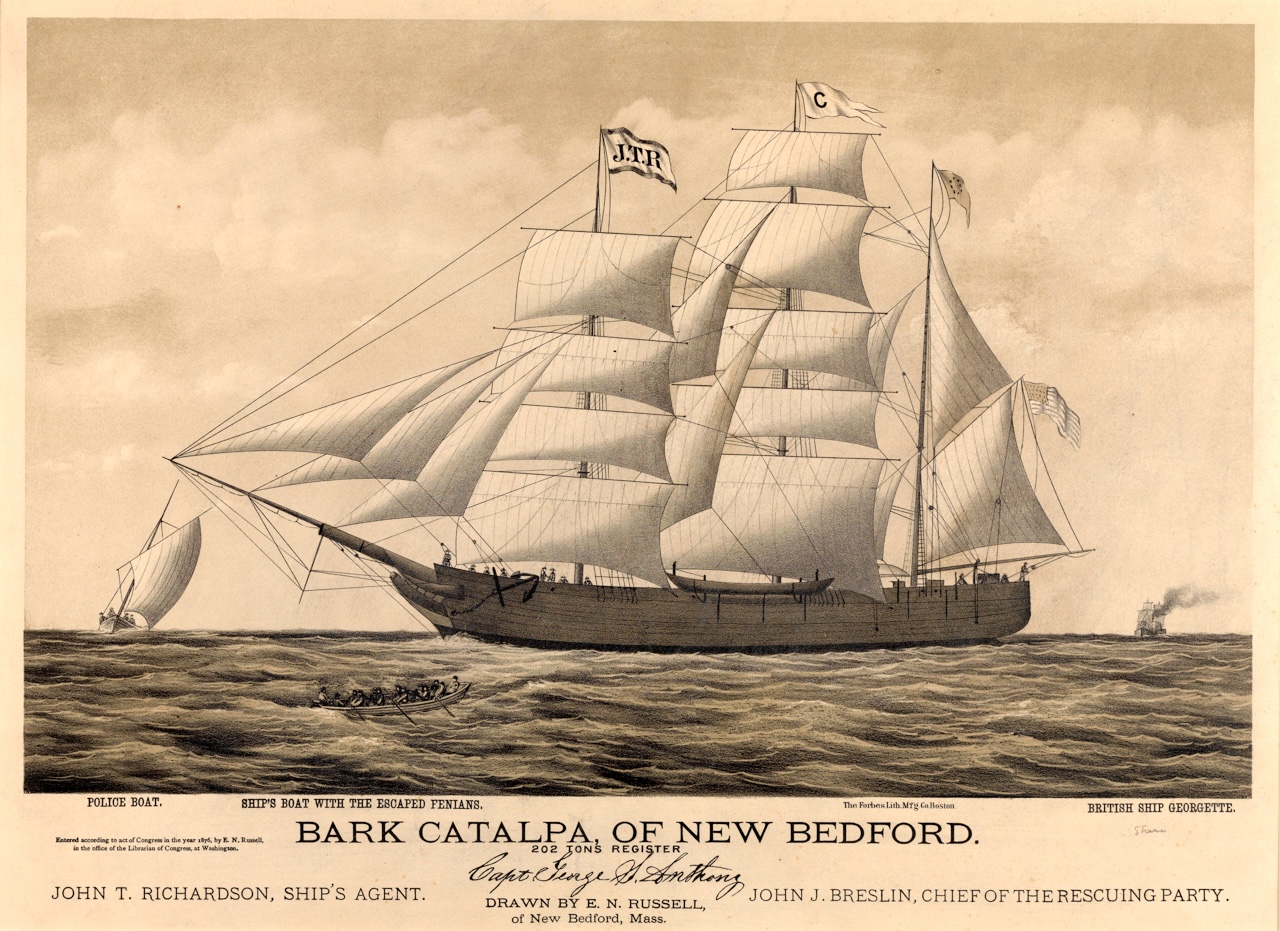

By 1875, all but six of the Fenians had been released. Back in Boston, O’Reilly and another Irishman, John Devoy, plotted to rescue the remaining prisoners. They bought a ship, the Catalpa, disguised it as a whaler,7 and sailed it to Fremantle. Meanwhile, two other Fenians traveled to Fremantle pretending to be a wealthy American businessman and a wheelwright.

It took 11 months, but the Catalpa finally reached Western Australia in March 1876. Plans were finalized, and coded messages were sent to the prisoners to prepare for an Easter Monday escape. The conspirators cut the telegraph lines between Fremantle and Perth to slow communications.

On Easter Monday, the six Fenian prisoners left with their morning work parties—probably waving cheerfully at the guards because they're Irish and Irish people are friendly—before dashing off to meet their getaway carriages and hightailing it to where the ship was anchored. A local saw them and raced to Fremantle to alert the authorities.

A storm prevented the escapees from getting to the ship, and they had to spend the night hiding out. They tried again the next morning, but the governor had sent an armed steamship overnight, which was waiting for them. The escapees barely reached the Catalpa first. As the Catalpa set sail for the open seas, the steamer fired a warning shot across their bow. Things were getting spicy!

The captain of the Catalpa quickly raised the American flag and announced that any shots fired at his ship would be considered shots fired on America. The balls on that one. Not wanting to create a diplomatic incident, the steamer reluctantly allowed the Fenians to sail away.

The whole thing was a nail-biter! The Catalpa sailed triumphantly back to America, where the Fenians were hailed as heroes. And ol’ John Boyle O’Reilly ended up one of the most famous and respected journalists and writers in the United States at the time,8 even writing a popular book about Moondyne Joe.

In the end, my visit to Colonial Alcatraz was an education—a deep dive into the bleak days of yore, presented with a cheerfulness that bordered on the surreal. For anyone yearning for a touch of historical misery with a side of heavy irony, this is the place. Just remember, the real escape is at the end of the tour, through the gift shop.9 “Don't forget to grab a souvenir!” Kevin beamed.

Write a comment