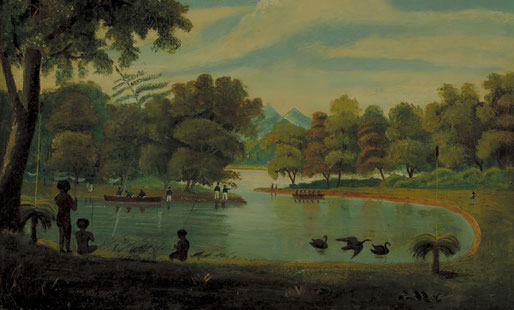

Once upon a time in 1829, on the sunny, sandy, and oh-so-inhospitable shores of Western Australia, the British, with their classic colonial optimism, decided to plant a flag and call it a day. Thus was the Swan River Colony born, named after the majestic local birds that float serenely on the river.

The colonists weren't the first Europeans to visit. The Dutch had come by as early as 1619, but they didn't hang around because the surf was choppy, and they had to hurry to the Spice Islands for an appointment to subjugate a different bunch of indigenous people. Another Dutch ship on its way to proto-Indonesia foundered decades later, which meant more Dutch people came by a couple years later looking for it. No luck. A hundred years go by, and the French show up, mostly to map it.

In other words, it’s not like Western Australia was a complete unknown. It was mostly an uncared-for. But the slowly growing interest—or more likely dawning awareness—on the part of other Europeans had the British crapping in their collective pantaloons. Especially when someone heard from someone else who heard it from a friend that the French (the French!) were thinking of creating their own penal colony on the west coast of Australia.

So Captain James Stirling successfully persuaded the British Crown to let him establish a colony there.1 He also pitched it as a free colony, meaning it would be funded by private capital, thereby limiting the cost to the Royal Treasury.2 Having been by before by Stirling from his perch on a ship 10 miles off the coast, he was 100% sure that it was the Land of Milk and Honey.3

The settlers4 were lured with promises of fertile soil and a positively Mediterranean climate. Yay! What they got was sandy soil as barren as their third sons’ prospects, with temperatures so hot they could grill a steak medium-rare on the pavement.5

Assuming they even made it to what would later become Perth, honestly. The first ship to arrive held a posh bunch of landed gentry dressed to the nines and sipping their tea with outstretched pinkies. They’d come well prepared for taming the Australian bush with things like upright pianos, carved sideboards, and trunks and trunks of frocks. As fate would have it, this first ship crashed on what was euphemistically named Garden Island. So they had to hang out there—piano-less by now, I assume—for about six months while The Smart People went off to survey and explore what would later become Perth.6

When they finally made it up the river to Perth, in a twist that surprised absolutely no one, the colony struggled. Food was scarce, the settlers were dropping like flies, and the only thing growing was the settlers' sense of resentment. Poor farming conditions led to food shortages and near starvation. By 1832, just three years in, the colony was shrunk to just 1,524 people. And that was followed shortly by a devastating economic depression just 10 years later, which led to more, erm, shortened life spans.

The point is that the colony was a veritable factory of fatalities, churning out dead bodies with the efficiency of a well-oiled machine. So they really needed to figure out what to do with them, or they'd all be driven mad by the flies. The flies! Oh, my Lord.

The city fathers established the East Perth Cemeteries in 1829.7 They selected the location with all the same care and consideration that went into the rest of the colony's planning—on top of a steep, barren, sandy hill. Because it’s hot in Perth, burials were only allowed to be conducted in the hour after sunrise or the hour before sunset to slow decomposition and maintain decorum.

(T)o, prevent indiscriminate burials and unpleasant consequences arising there from, in a warm climate…(a)ll burials by the Chaplain must take place as soon after Sun rise as possible or an hour precisely before Sun set, and at no other time unless circumstances should render it absolutely necessary and twenty-four hours previous notice must be given to the Chaplain.

– Governor James Stirling, 13 February 1830

Initially, the cemetery was a non-denominational final address, though it was nominally managed by an Anglican minister. The keys to the kingdom were officially handed to the Church of England in 1842. But as the years rolled by, the dead diversified. Not everyone wanted an Anglican burial in an Anglican cemetery.8 The Roman Catholics claimed a separate section in 1848. The Congregationalists and Methodists, not to be outdone, claimed theirs in 1854. The Jewish community and felons got their own sections in 1867, the Presbyterians in 1881, and the Chinese in 1888.

Things really heated up in the early 1890s with the gold rush—you know, sudden overcrowding and a lack of infrastructure led to poor sanitation, diseases like typhoid and tuberculosis, and angry drunk people who were often disappointed by something.9

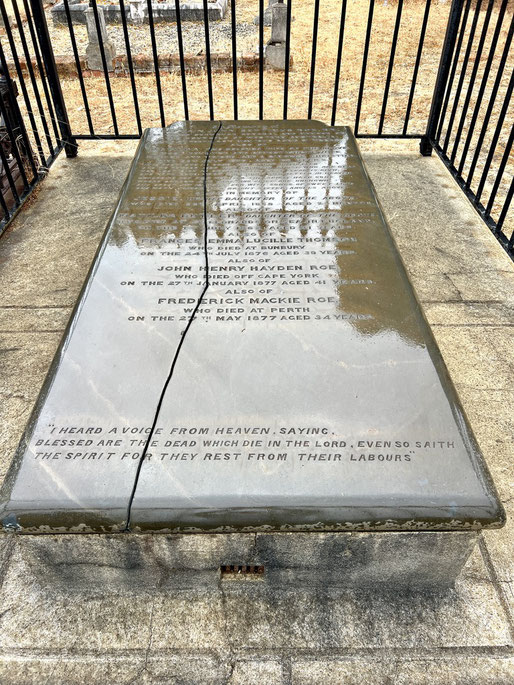

The cemetery was a veritable who's who of early Perth,10 everyone from the wildly optimistic to the downright unlucky.

Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Clarke, a distinguished Irish soldier and administrator appointed as the third governor of Western Australia, sadly came down with something deadly shortly after arriving and expiring six months later. He was, however, the first governor to be buried in Perth. Apparently, his predecessors had been rich, so they could afford to have their bodies sent back to Britain for burial.

Cleopatra Palmer, daughter of Henry Palmer, died at 21 in 1895. I don’t think there’s a story there, but I sure like her name. Bonus: Her brother’s name was Cicero!

John Septimus Roe, who, clearly armed only with a faulty ruler and a massive ego, platted the entire city of Perth.

John Henry Monger, Jr., a merchant prince and legislative luminary, is buried under perhaps the grandest monument in the Methodist section with his wife, Henrietta Joaquina. Just another awesome name.

George John Hollis, dead at 60 in 1879, but whose headstone is carved on the back of someone else’s, Ellen Landor—an Englishwoman who’d married a respected Perthling lawyer, author, newspaperman, explorer, and man about town, and raised four children. What the hell’s that about?

Things finally got so unpleasant up the hill that they closed the cemeteries to all further burials in 1899, and they’ve been deteriorating ever since. More than 10,000 people were buried in these cemeteries, but only 800 gravestones remain. The average age of people buried here was under 30 years. Thirty-five women buried here died during childbirth. And a shocking 32 percent were infants and young children. Hey, life was tough.

Ultimately, the Presbyterian, Jewish, and Chinese cemeteries were “relinquished” to the state’s Education Department. So, the Chinese are now currently buried underneath a school for girls. And the Jewish graves sit under a bunch of condos. Classy. And weirdly, because I'm just not sure how you let this sort of thing happen, they've just plain lost the convict cemetery.11

There you have it, a not-so-brief history of the East Perth Cemeteries, where early settlers' dreams of a new life always ended up six feet under. Even in a land as beautiful as Western Australia, Mother Nature—and colonial incompetence—is an unforgiving mistress.

Write a comment