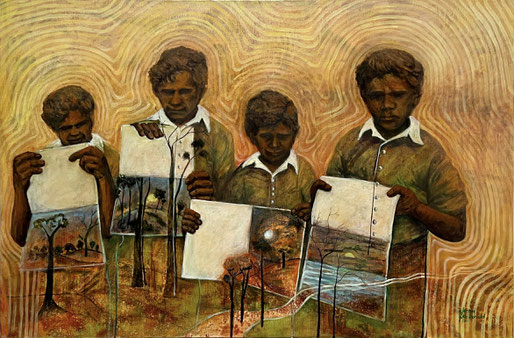

Kintyre, 2021 (multiple artists)

Rick and I love art galleries. So much. Sometimes they're just an excuse to get lunch or a drink at the café or that great restaurant across the street. And we've been surprised by the cool factor of all the state galleries we've visited here in Australia.*

I haven’t come up with a good way to write about them yet, but I have decided not to let that stop me! Let’s practice with the Art Gallery of Western Australia,** shall we?

Surrounded by the main museum, the state library, the contemporary art gallery, and the performing arts theater complex, AGWA is the beating heart of Perth’s Cultural Precinct. It's also just across the street from the central train station and mere blocks from the center of downtown. So, you know, pretty handy.

Since 1895, AGWA has served as the primary art institute in Perth. The current museum—a modernist design inspired by the National Museum of Anthropology of Mexico in the 1960s—might suggest a staid, sober institution. But just step inside, and you'll find a space alive with the vibrant energy of more than 18,000 works that span continents, cultures, and centuries—right here in little ol' Perth.

The gallery has a vast collection of artworks by First Nations and Western Australian artists, alongside works from around Australia and the world—20th-century Australian and British paintings and sculpture are a particular strength. A recent rooftop redevelopment created one of the largest rooftop spaces in Western Australia. This area now hosts a sculpture garden (sculpture roof?), rooftop bar, and event space—all with an incredible view of the Perth skyline.

Targets, 2020–21 (Christopher Pease)

The bathers, 1989 (Mark Tansey)

A rock, a pool, 1959 (Robert Juniper)

little mermaid + intimate friends, both 2021 (Luisa Hansal)

The AGWA spotlight shines brightly on the Indigenous artworks that form an integral part of its collection. With more than 3,000 works by Aboriginal artists, the gallery is clearly sincere in its aim to put Aboriginal stories on equal footing with colonial stories and to celebrate the full history of this place. Every piece captures the vibrant hues of the Kimberley region, the ancient Dreamtime stories, and the resilience of Aboriginal communities, inviting visitors to immerse themselves in a world where art is not just seen but felt.

This is where tradition meets innovation, where ancient techniques find new expressions in the hands of modern artists. This commitment to celebrating Indigenous culture is not just about preservation; it’s about igniting conversations, challenging perceptions, and opening hearts and minds to the rich tapestry of stories that define this land.

Spirit drawn, 2008 (Norma Macdonald)

My Heartland, no date ("Swag" Graham Taylor)

South-West landscape near Pemberton, с1962 (Revel Cooper)

From our lip, mouths, throats and belly, 2021 (Amanda Bell)

The Noongar word "moorditj" means good, or even awesome, in English. It conveys a glowingly positive energy that Bell—a Badimia and Yued woman—uses to express loving connections across generations and geographies.

Oa Warrior II (pink), 2020 (Reko Rennie)

Maralinga, 1990 (Lin Onus)

Maralinga is the Australian desert site for the U.K.'s atomic bomb tests in the 1950s. It has become an enduring symbol for desecration and pollution—and a commentary on the compulsory displacement of Aboriginal landholders from their traditional land.

Special exhibits—such as Yhonnie Scarce’s The Light of Day—also demonstrate AGWA's dedication to exploring complex themes with nuance and sensitivity. These exhibits don't just showcase art—they invite contemplation, offering visitors a space to confront the universal truths of mortality, memory, and identity. Scarce, a Kokatha and Nukunu artist, explores our unbreakable connection to the past in a way that is both personal and universal. Her exhibit spanned three huge gallery spaces across two levels, creating a monumental showcase that, rather than overwhelming, offers visitors the time and space they need to engage with the art and the stories it holds.

Apparently, the installation for this exhibit was the most complex ever undertaken by the gallery—especially with regard to Scarce’s immense hanging installations, including “cloud series” works that have never been shown together before. These installations—like Death Zephyr, Thunder Raining Poison, and Cloud Chamber—are abstract representations of the nuclear testing in the Maralinga desert, which impacted not only the land but also the lives of its Aboriginal inhabitants.

Thunder Raining Poison, 2015 (Yhonnie Scarce)

Death Zephyr, 2017 (Yhonnie Scarce)

Other, more intimate parts of the exhibition included a beautiful mixed-media work, Oppression, Repression (Family Portrait), that digs into Scarce’s family history and the experience of Aboriginal people in Australia. Set alongside her larger installations, this piece demonstrates the depth of her art.

Family Portrait, 2008 (Yhonnie Scarce)

In the end, we were expecting a cowboy museum in Perth—but we found a world-class gallery that uncovers the area’s enduring connections between the land and its people. You’re not going to find another place like this outside of Australia.***

Painting for a New Republic (The inland sea), 1994 (Gordon Bennett)

Write a comment