“Oooh, an asylum for the criminally insane gives tours!” I said to Rick. “Wanna go?”

“Oh, hell no,” he said.

You know, I get that response a lot to my very best ideas. Oh well.

So I went alone to the somewhat eerie halls of the infamous Z Ward at the Glenside Hospital in Adelaide.* My visit was a glimpse into a past where the lines between mental health treatment and outright incarceration were, hmmm, let's say, a bit blurred?

I'd really, really hoped that this lunatic asylum would look like Arkham, but, sadly, it did not. Part of that is because my mid-afternoon visit occurred on yet another perfect and sunny day in South Australia. Another part of it is that Arkham doesn't exist outside the comics. Too bad.

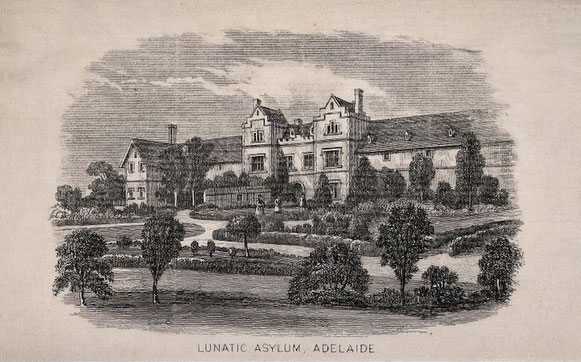

Adelaide, founded in 1836, was just starting to bustle, as it were, when the city elders decided the burgeoning population needed a place to house those considered mentally ill. By 1845, the

Adelaide Gaol was home to several inmates who were segregated from the main population due to mental health issues. But, as you might imagine, jail isn't ideal for mental care. So the city built

its first asylum in 1846—just a bit out of town to keep the inmates patients out of sight and, presumably, out of mind.

Things went swimmingly for a while—almost 20 years, in fact. But then the fine citizens of Adelaide, specifically those in the neighborhood of the asylum, began to complain vehemently that the

inmates patients were loud, distracting, and generally a nuisance that ruined their genteel lives.

So the city began building the Parkside Lunatic Asylum, a complex of buildings used as a psychiatric hospital, which opened in 1870. The asylum soon became a catchall for not just the mentally

ill but also a variety of societal outcasts genteel Adelaide society found, um, inconvenient—from unmarried mothers to the terminally ill. The conditions, by today’s standards, were far from

therapeutic. Roughly a third of the inmates patients met their end within the asylum’s walls.

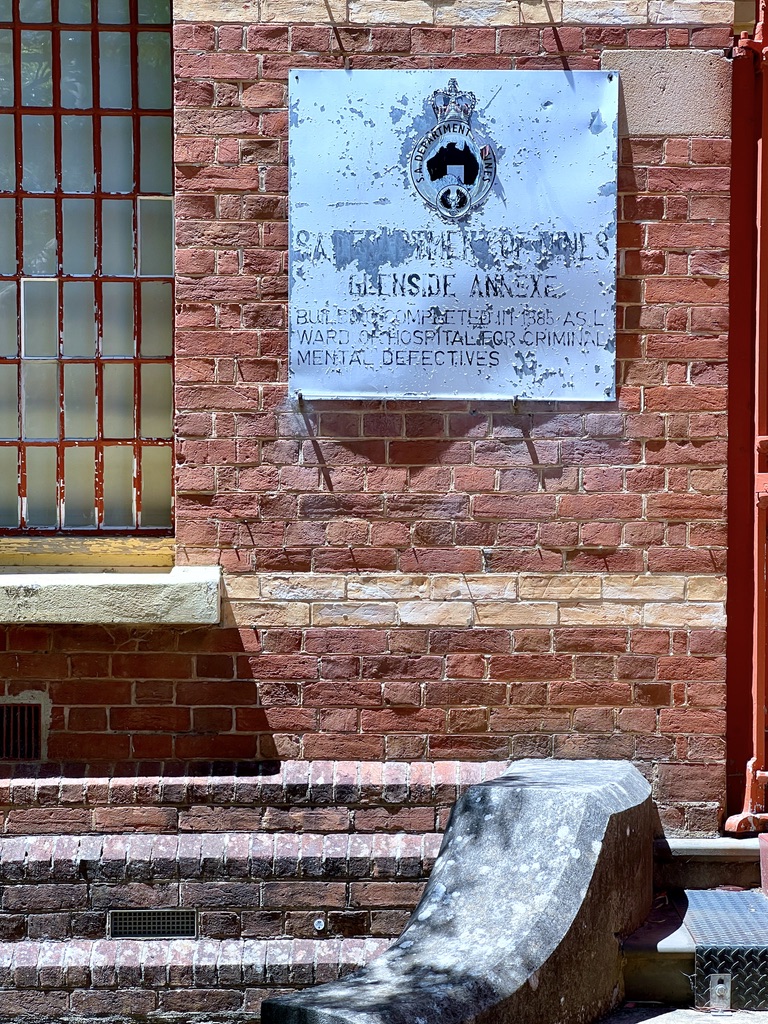

And then there's the Z Ward, which was designed specifically for the “criminally insane”—a term that is both mysterious and dreadful. The building itself is gorgeous, with elaborate polychromatic brickwork that is considered the best of its kind in South Australia. It adds a nice veneer of sophistication to a place with such grim purpose. The infamous “ha-ha wall,” which looks shorter from the outside than it really is, seemed the physical embodiment of the era's approach to mental health—an illusion of normalcy masking a harsh reality.**

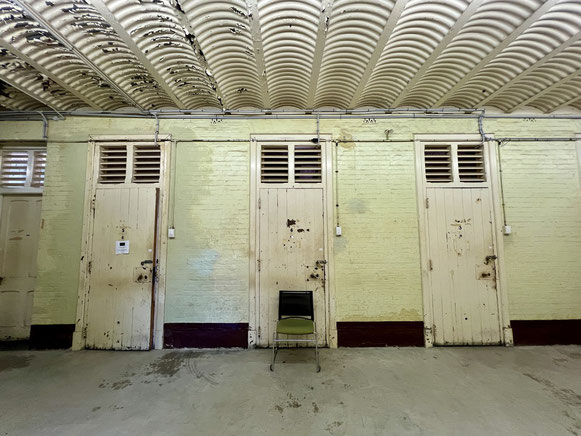

Admitting a new member to this exclusive club was a ritual in itself. A bell chime at the gate would summon a key-wielding attendant, whose sole purpose was to navigate a maze of locked doors,

almost as an abject lesson in the futility of any escape attempt. “Special guests” of the Governor (so-called “Governor’s Pleasure” inmates patients,*** or

those found not guilty by reason of insanity) were given prime real estate—ground floor cells, separated from their peers by a cyclone screen.

But not everyone in the ward was a Governor's Pleasure patient. In fact, most were minor offenders, deemed too unstable for jail but just right for an asylum stay. Another smaller group was made up of those considered to be dangerous to themselves or to others and were placed there for the protection of the larger Asylum's other patients.

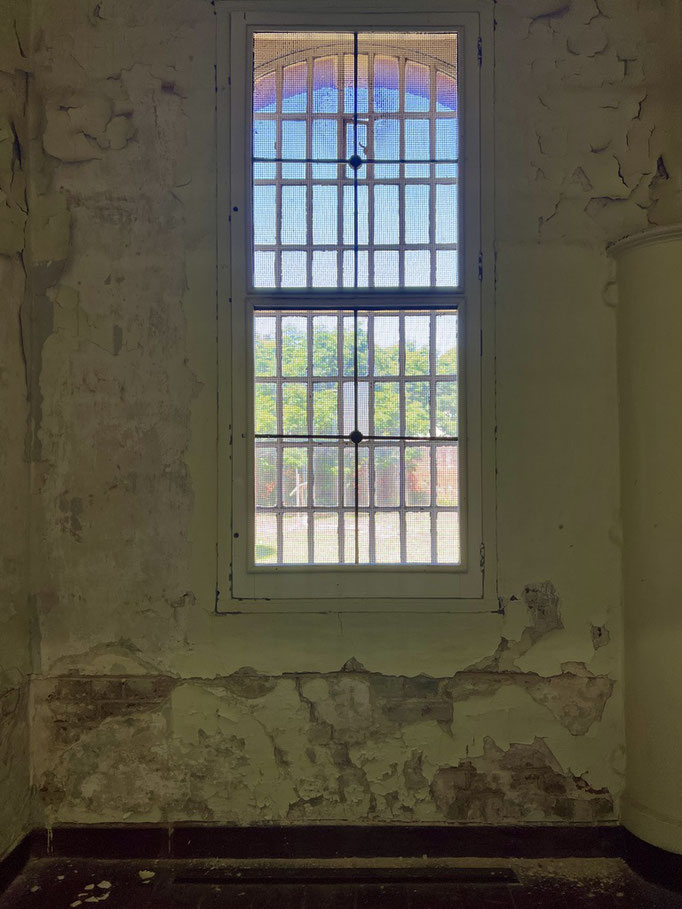

It wasn't fun for anyone, I don't think. The cells are small, unlit, and unheated. Patients had to report to their cells by 4 p.m. and put their clothes in a pile outside the door.† Strolling through the rear yard, the walls tell their own tales. The softer sandstone bricks bear the scars of time and idle hands, with gouges from patients who wandered around the yard with their fingers trailing along the walls. Like a guestbook but etched in stone and sad. Symbols and dates scratched into the stones further serve as silent testament to the stories that unfolded within these walls.

There's a misconception—and my being a bit glib doesn’t help—that Z Ward was a place of severe punishment and brutality. But while conditions were tough, patient treatment was in line with the standards of the time.

Initially, bed rest and isolation were the primary means of treatment. But as trends changed, so did standard treatment. In the late 1800s, chloral hydrate, bromides, paraldehyde, and barbiturates were used to control “the restlessness of general paralysis and senile dementia.” Mostly, I think, it made the patients sleep.

In 1929, malaria treatment—infecting patients with a “mild” form of the disease—was introduced. A year later, arsenic treatment was introduced to curb the influx of syphilis-derived dementia. By 1938, they were intentionally putting patients into diabetic comas with “insulin shock treatment” and inducing “convulsive therapy” with chemical injections. ECT (electro-convulsive shock treatment) started in 1941. The first psychosurgery procedure—and I assume we’re talking lobotomy here—was performed here in 1945.††

By the late 1950s, breakthroughs in modern drug treatments began to show promising results, and patient numbers in the asylum slowly began to fall.†††

The Asylum—as a whole, not just Z Ward—was colloquially known as “The Bin,” reflecting a time when society's approach to those of us who don’t fit the mold was to, quite literally, throw them away. That’s a jarring thought, especially when considering that alongside the mentally ill were people whose only “crime” might have simply been societal non-conformity.

Despite that, many patients became acculturated to the routine of the hospital. They began to fear life outside—to the extent that they didn't want to leave. The institution was self-sustaining, to an extent, relying on the labor of its residents. Patients were expected to work two to three hours each day, tending gardens, mending clothes, and even farming livestock. In a way, it almost sounds like a community for people deemed unfit for the larger world.º

Walking through the corridors of Z Ward,ºº it's hard not to be struck by the stark contrast between past and present mental health practices. The evident signs of monotony and frustration etched into the building itself speak volumes about the lives of its inhabitants. It's a sobering reminder of how far we've come in our understanding and treatment of mental health.

Write a comment