Ah, Melbourne—city of art, coffee, and...a rather imposing 19th-century prison?

My adventure to the Old Melbourne Gaol, a relic of Australia's less Instagrammable past, was a solo one, with Rick feigning disinterest in “antique torture chambers.”*

The gaol’s** façade struck me as a strange contrast against the modern cityscape, plopped as it is right in the middle of modern, growing Melbourne, standing like a stern relic of a bygone era. It's like stumbling upon a haunted mansion at the end of a cul-de-sac lined with super-trendy cafes.

Established in the 19th century, this prison is a stark reminder of Australia’s rough colonial past, when the British Empire seemed to believe the solution to every problem was either a cup of tea or a prison beating. There was just no in-between for those guys back then. Melbourne was not founded as a penal colony like Sydney, Hobart, Moreton Bay, and Perth. But it was still a wild, dangerous city.

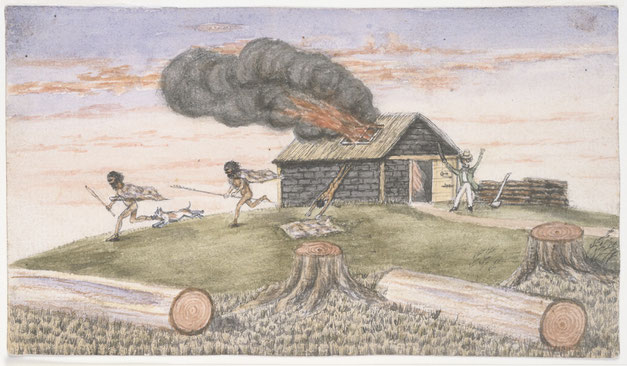

Initially, Melbourne was mostly a farming community. The availability of good land led to some overcrowding. During Melbourne's early years, lawbreakers were jailed in small, poorly built wooden lockups. The city’s first jail was burnt down by Tullamareena—a Wurundjeri headman who escaped after being arrested for stealing sheep.

The Victoria gold rush strained the whole broken system. Massive numbers of immigrants came. Included in that flood were plenty of reckless characters looking to hit it big. More often than not, though, they just ended up restless and frustrated at best and destitute at worst.

So Melbourne needed a much bigger, better gaol, which they built out of non-flammable bluestone and opened in 1845. The bluestone is dwarfed by neighboring buildings today, but back in the day, it was a looming presence on a small hill overlooking the rest of Melbourne.

By 1850, it was already overcrowded, so they expanded it in 1852 and added a female prison block in 1864. Ultimately, the prison occupied an entire city block,*** with exercise yards, a hospital, a chapel, a bathhouse, and staff quarters.†

Ultimately, the gaol operated from 1845 to 1924 and housed everyone from petty thieves and the homeless to notorious criminals and the mentally ill—all of whom I assume were equally unenthused about their accommodations.

It was also home to up to 20 children at a time—some convicted of petty theft or vagrancy and others who had to accompany a convicted parent. Babies younger than 12 months old were allowed to be with their mothers. The youngest prisoner was recorded as 3-year-old Michael Crimmins, who spent six months in the prison in 1857 for being idle and disorderly.†† In 1851, the 13- and 14-year-old O’Dowd sisters were imprisoned because they had nowhere else to go.†††

The gaol is three levels. Prisoners convicted of serious crimes, like murder, arson, burglary, and rape, would start in solitary confinement on the first floor in cells so cramped they make economy-class seating look like a luxury. They were forbidden from communicating with other prisoners, which was strictly enforced by wearing a rough calico hood or silence mask whenever they were outside their cells. Which was not often. They had a single hour of solitary exercise a day and spent the other 23 hours in their cells. The forced alone time was probably better for everyone—they were only allowed to bathe and change clothes once a week.

If they behaved downstairs, the prisoners could move up a floor. They were also granted the “luxury” of work—men would break rocks and the women would sew, cook, and clean.º

Prisoners who had become trusted (stooges?) and those near the end of their sentence were moved to the third floor with the “minor” criminals—people convicted of things like drunkenness, vagrancy, prostitution, or petty theft. The cells on the third floor were bigger and held more than one person, though they were still pretty grim. It’s like being upgraded from solitary to a hostel—not ideal, but you take what you can get.

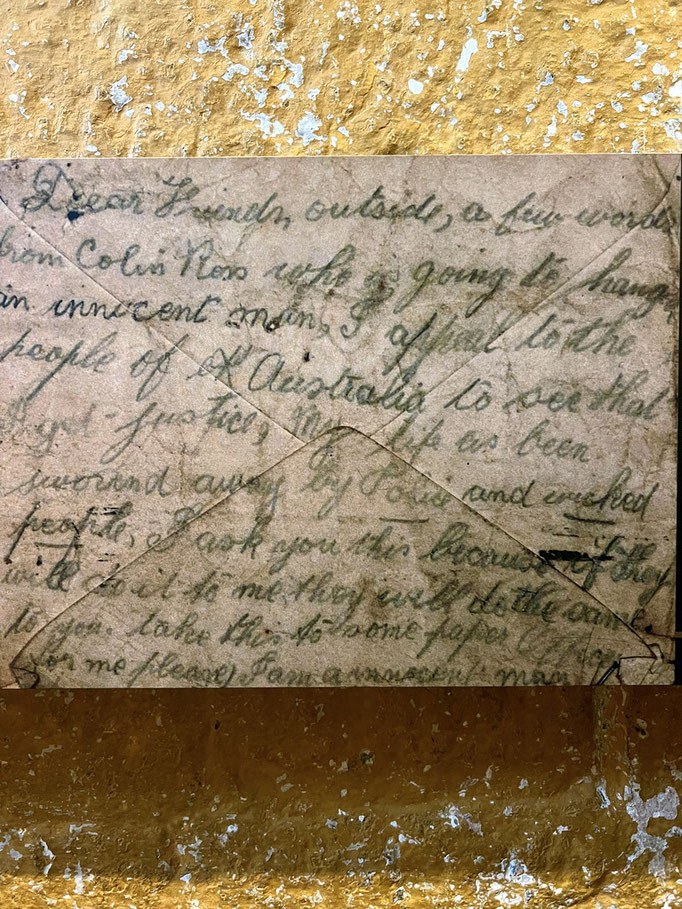

A morbid highlight was the gallows. Originally outside in the yard, they moved the rope inside onto the third floor in the octagon at the central axis point of the prison block. That’s where they hung Ned Kelly, arguably Australia’s most famous criminal. His story is woven into the fabric of Australian folklore. His life, filled with daring escapades and a controversial end, seemed to encapsulate the spirit of an era of rebellion and resistance against authority—part Robin Hood, part notorious killer.

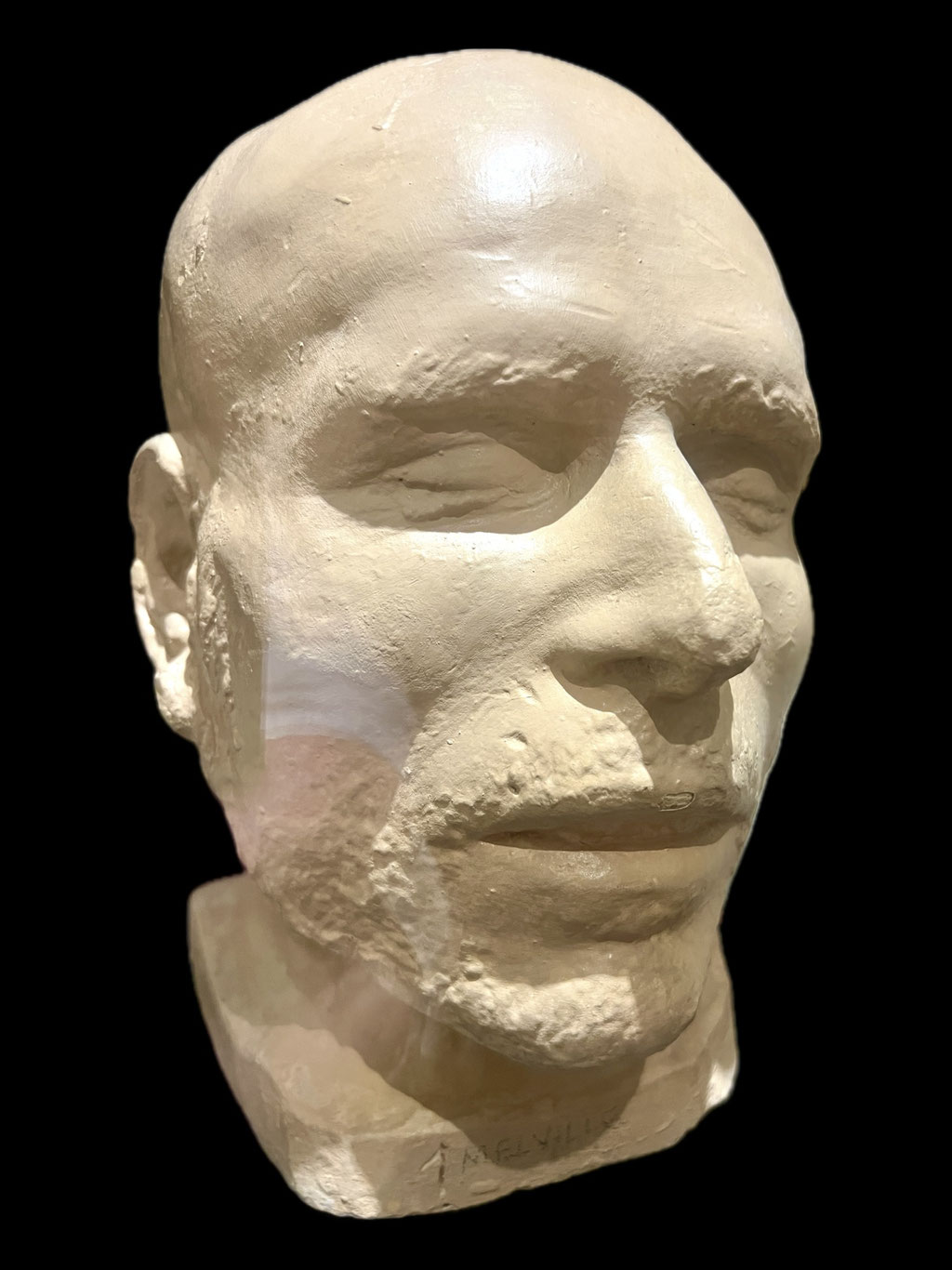

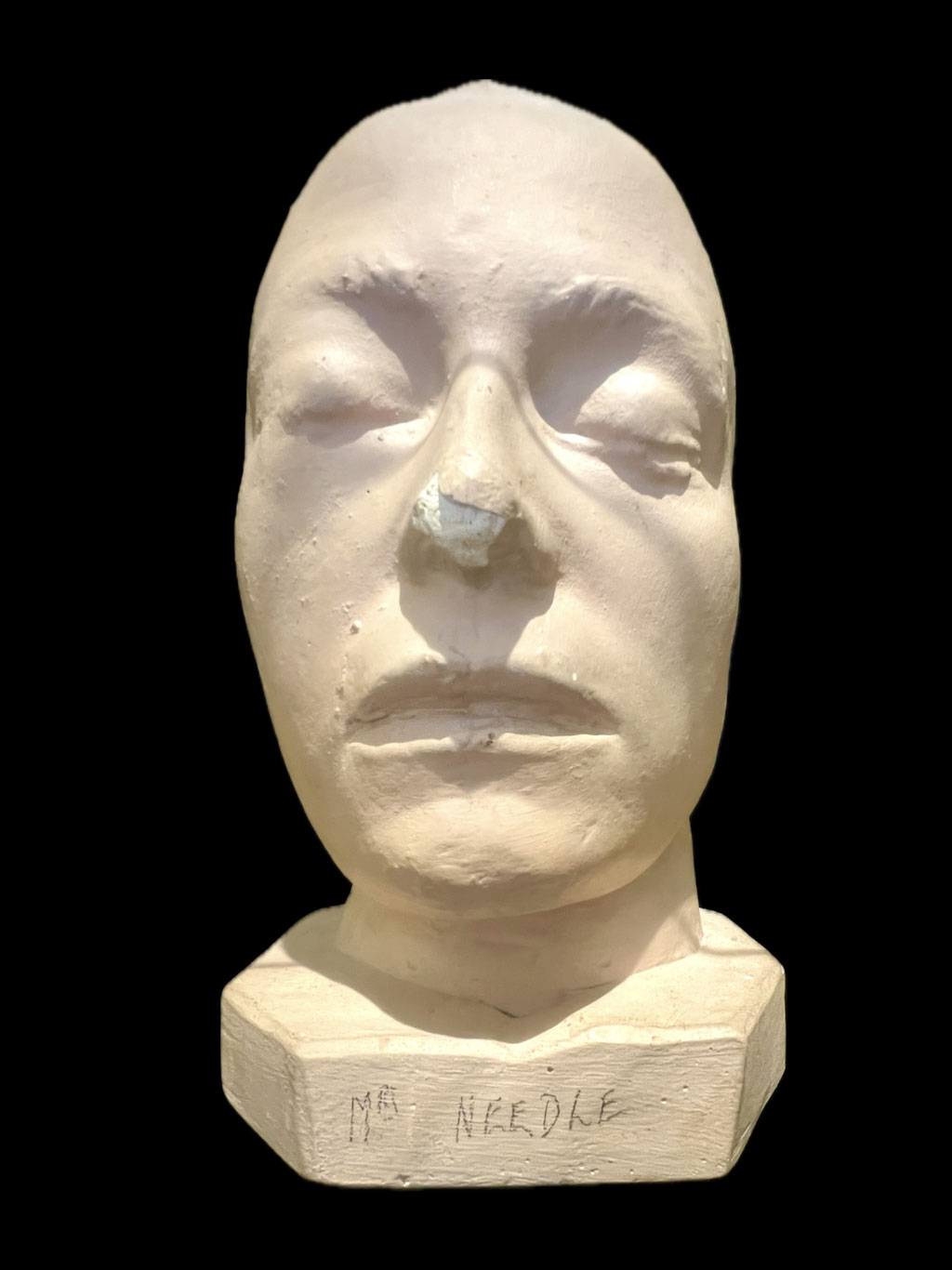

Among the more macabre exhibits were the death masks, plaster casts of post-execution criminals’ faces. Why? Because they were BIG into phrenology back then. You know phrenology—the quintessential Victorian hobby of judging a book by its cover. “Skulls are just bone bowls for brains. They’re a mystical roadmap to the soul!” The sheer absurdity of thinking you can judge someone's inclination toward crime or art by massaging their lice-ridden head is like confidently buying a car after kicking its tires—a “charming” blend of overconfidence and under-science.

My gaol tour was a potent reminder of evolving of penal practices.ºº The harsh conditions and brutal punishments seemed medieval compared to modern standards. Corporal punishment, flogging posts, and time in irons—a sobering reminder that the past, while fascinating, was not always a place for justice or compassion and a far cry from contemporary ideas around rehabilitation and reform. That said, I’m not keen on experiencing a modern prison, either.

Rick may have been right to skip this one.

* Clearly, he was faking it. Who wouldn’t love to wander around a historic torture chamber?!?

** And, yes, I will be using the ridiculous English spelling in this story. When in Rome Melbourne….

*** And the blocks in Melbourne are BIG, I’m telling you. Saying Melbourne's city blocks are “big” is like saying the Sahara is sandy. Navigating these blocks is all about endurance. So a prison that covered a “whole city block” isn’t just a prison—it’s a mini-fiefdom in the heart of the city.

† By 1860, there was a house for the chief warder and his family and 17 homes for gaol guards on Swanston Street in 1860. Before that, jailers and their families had to live inside the prison walls. Wow. What’s the word for an anti-perk?

†† Um…3. Years. Old. Arrested for being idle and disorderly. Did he refuse to pick up his Legos?

††† Their father ran off to mine gold up north, and their mother died of typhoid. Or maybe just overwork. Overall, this visit made me a bit more appreciative of modern life.

º I am rolling my eyes so hard right now I’m having trouble seeing the computer screen.

ºº Oh, I went there. Obviously, the phrase "penal practices" possesses a certain, shall we say, adolescent charm. The mere mention in a historical context like this sends the mind wandering down a path that's less “academic symposium” and more “middle school boys locker room.” Sure, the gaol was, you know, sad. And many, many terrible things happened there. But c’mon…“Let’s discuss the evolution of penal practices at the Old Melbourne Gaol.” Hahahaha! No matter how dismal the topic, there’s always room for juvenile humor.

Write a comment