If you’d asked me to guess what was inside a British architect’s house from the late 1800s, I would have assumed blueprints, drafting pencils, and maybe a few really cool models. But walking into Sir John Soane's former-home-now-museum is like walking into the house of that one crazy uncle who hoards National Geographics, empty cigarette cartons, and every letter he’d ever received between 1975 and 2012 when people just stopped sending letters.

But it turns out Sir John had more money and different tastes than that crazy uncle. So his hoarding has been called “collecting” and the objects he “collected” are art and antiquities. And he “collected” so much of it that he had to buy the two houses next to his just for the space to keep adding more stuff. My kind of guy. I mean, my extra-houses room would be filled with shoes, but whatever.

He also donated his entire treasure trove to the City of London upon his death—under the stipulation that everything be kept exactly as it was when he died. Oh the delicious morbidity!

We started in the basement because, well, that’s where they told us to start. That’s where the kitchens are located, the epicenter of bustling staff. Tidy and spare, it looked like these rooms had been dressed by a set designer with a predilection for historical accuracy. It felt “normal” and maybe just a tiny bit disappointing based on my expectations.

But don’t worry, the kitchens are an island of calm a world away from the rest of the house, and things got crazy the minute we left the pantry. The rest of the basement is packed to the brim with random pieces of Sir John’s personal collections and curiosities from around the world. The Monk’s Parlor, inspired by his friend Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, is where he would entertain guests—a small, dark room decorated with Gothic stained-glass windows, paintings of monks, and a skeleton in a glass case. Because nothing says, “Thanks for coming by. Sherry?” like a skeleton in a glass case.

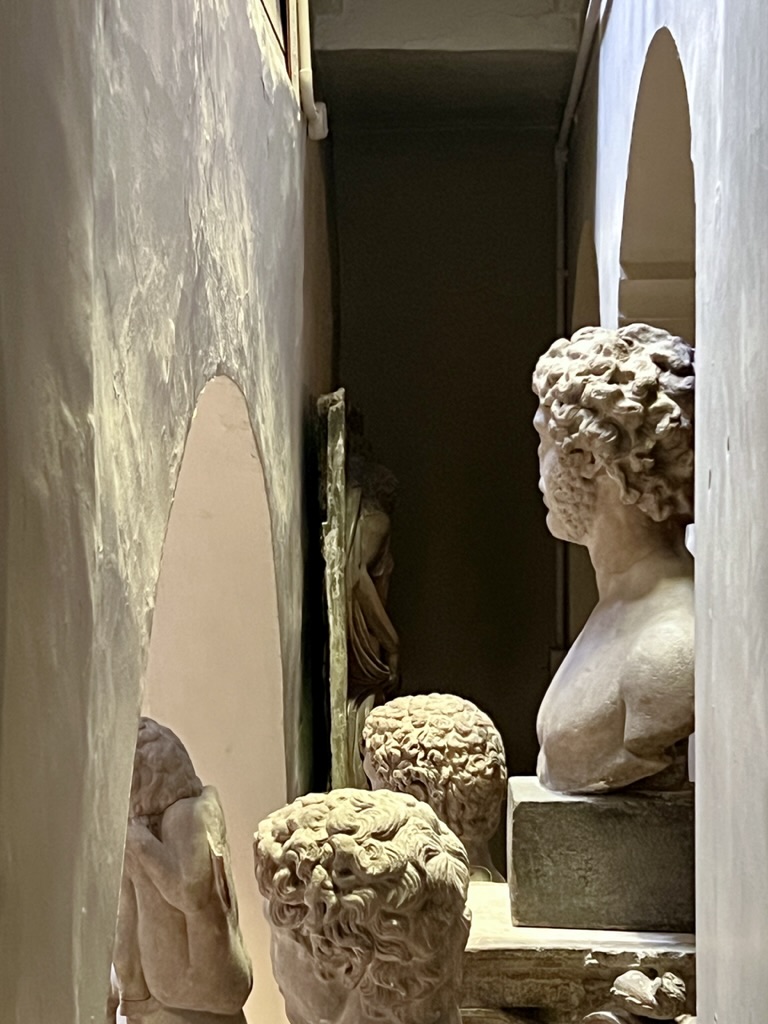

The Colonnade is stuffed with works by Canaletto, Hogarth, Turner, and Fuseli jumbled together with Sir John’s own paintings, his designs for the Bank of England, architectural models, random sculptures, and a cork model of Pompeii. All of this leads to the Crypt. What’s there? Only the sarcophagus of Egyptian pharaoh Seti I. Because when you’re a 19th-century architect with a collection addiction, an empty Egyptian sarcophagus is the only sensible choice as a centerpiece.

Upstairs was more of the same. And by that I mean it was more of everything. Like a shaken snow globe full of art and history, and wherever the pieces landed is where they stayed. An assault on the eyes, but, you know, in a good way. Paintings, antiquities, building fragments—anything you can imagine and plenty more you can’t. From the second floor, you can peek down on the sarcophagus, which made it less creepy and more cool.

My favorite room upstairs was the small library. There are tons of books throughout the house, but this was the only place where they weren’t shelved behind glass doors. I really, really wanted to pull one down and see what was inside, but there were hyper-attentive docents covering every square inch of the place.

We were only allowed as far at the second floor, a discreet “Staff only” sign roped off the stairs up. But oh man how did I want to go up there. If the third and fourth floors were as packed as the first three, what was I missing? Probably something amazing. I imagine that’s where the bedrooms were. How cool would it be to wake up surrounded by a cache of rare Greek urns or falling asleep while reading by the light of a Roman oil lamp? Messy, probably, and I’m sure I’d stub my toes a lot. But it would be worth it.

From the outside, Sir John’s house looks pretty normal. But we walked away with a newfound appreciation for eccentric uncles everywhere. At least the really rich ones, anyway. Their houses might be chaotic, their collections unruly, and their shelves a real pain to dust—but within all that is a kind of magic you'd be hard-pressed to find anywhere else.

Write a comment